THE DE TOMASO VALLELUNGA

Click on pictures to view a larger, clearer version.

The following two articles have been copied from two magazines. The first

is from an article from Thoroughbred & Classic Cars, August

1997 edition. This is a magazine intended mainly for the United Kingdom.

The text is reproduced here in its entirety with a few American English

modifications.

The second is from an article in the September 1991 issue of Road &

Track Magazine. For more information and pictures, visit the DeTomaso

homepage.

In August 1997, I went to the Concours Italiano in Carmel Valley, CA.

Tom Mantano's (see bottom article) red Vallelunga was featured there and

I got to meet him and sit in the car. See my Concourse

Page for more pictures.

Formula First

By Malcolm McKay

From Thoroughbred and Classic Cars, August 1997

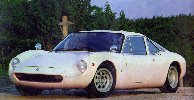

De Tomasos"s first road car was the Vallelunga. The first production sports

car to have a mid-mounted engine, it used a sixties state-of-the-art suspension

based on an F3 De Tomaso racer. It was a Formula first. Fire it up and

the noise is deafening - literally. Ear defenders are an essential if you're

to enjoy driving this car: and enjoy it you will. Get the lusty twin-Webered

Cortina lump into the upper rev ranges and it roars, it booms, and it thrusts

the little car up the road with astonishing alacrity. Combine this power

with a racebred Hewland five-speed gearbox where third, fourth and fifth

are so close that there seems barely a 1000 rpm drop when you change up,

plus Rose-jointed state-of-the-art suspension that was identical and interchangeable

with a Formula 3 De Tomaso racer of the day, and you have a recipe for

serious fun on open roads and circuits.

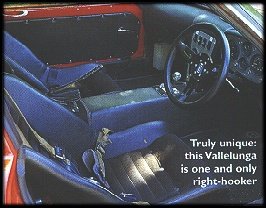

The driving position is excellent with reclined race-style seats, super-short

gearstick and pedals close together, offset but still fine - at least for

drivers with average-size feet - for heel-and-toe gearchanges. The short

gearstick has a clearly defined alloy gate but can be very difficult to

engage, especially when cold. First and reverse are most difficult and,

to make matters worse, reverse is where you would normally expect second

to be. Thankfully a flap prevents you engaging reverse by mistake as long

as you remembered to flip it back after your last attempt to get reverse...

The oddish layout then continues, with an H-pattern for the other four

gears that sees third and fifth at the top of the H, second and fourth

at the bottom. Once familiar, however, it can be snicked from gear to gear

without hesitation.

Initially, you potter away keeping the revs below 2500; the engine is

quite tractable and noise is - just - bearable. Above 2500 the most appalling

vibration sets up that shakes the whole car, you can see nothing in the

mirrors and the best advice is to floor it through to 3500 where it smoothes

out again, albeit accompanied by a headache-inducing boom. Herein lies

the major disadvantage of the car: every vibration in the engine, transmission

and suspension is amplified through the chassis, trapped inside the body

and transmitted into a masochistical massage for the driver. It says a

lot for the car's handling and performance (or is it my state of mind?)

that after 200 miles driving I was still in love with it.

The four-point harness holds the driver firmly in the comfortable seats;

one's confidence is only slightly jolted on seeing that the top mount of

the harness is bolted to a steel strap the end of which is bolted to the

engine mounting plate; after all, the whole car is bolted through the engine

mountings. The car is remarkably tractable in traffic and stays cool despite

a tiny radiator in the nose. The clever use of blackpainted mesh for the

rear panel, with the Fiat 850-derived rear lights and the numberplate set

into the mesh, helps to keep engine bay temperatures down, but after a

spell stationary the car is prone to pinking until it's had time to cool

off again. Accessibility with the huge Perspex, steelframed rear window

lifted and the plywood deck lid removed is remarkably good, provided you

don't mind climbing in and standing beside the gearbox. Further development

would, I am sure, have enabled De Tomaso to put in a luggage locker or

two in the rear deck over the gearbox - there's loads of space behind the

engine.

On bumpy roads, the little car is lively to say the least; belt it round

bumpy bends and the tail jumps sideways. The steering is light and razor-sharp,

and on smoother roads cornering powers are phenomenal; it scuttles around

corners and roundabouts with negligible roll and perfect poise. Pushed

really hard it gave the impression that rear-end breakaway, when it did

come, would be sudden, but that's the philosophy of race-car design: hold

the road above all other considerations to the ultimate possible point.

With no servo, the brakes require a firm shove but, given that, they

are immensely effective. just as well, for it's not merely the only one

in the country but the only one built for the British market and the only

one of the 50-odd Vallelungas built that was right-hand drive: Duncan Rabagliati's

car truly meets the much abused term 'unique'. It's also one of the most

beautiful cars ever made; how dare it be so rare?

Initially, Alejandro de Tomaso concentrated on building racing cars,

and eventually ventured into F1, F3 and even Indianapolis but, like all

De Tomaso's early cars, they suffered from a lack of development. Meanwhile,

in 1962 De Tomaso completed a road sports car with great track potential,

naming it after the Rome racetrack he often used for testing: Vallelunga.

The revolutionary chassis used the mid-mounted in-line four-cylinder engine

and five-speed gearbox as load-bearing members: indeed, the load-bearers

for the back half of the car. Bolted solidly to the engine mountings was

the rear end of an upturned U-shaped spine chassis, surprisingly narrow,

which opened out up front to carry the front suspension. The claimed resemblance

to the Lotus Elan is actually not that great; besides, De Tomaso had used

spine chassis before.

The engine chosen marked the start of a vital link for De Tomaso, a

theme he would maintain throughout his road cars: it was from Ford. In

this case, Ford of Britain: a Cortina GT 1500 unit with twin Webers, giving

104 bhp. A 135 bhp option was listed too; the engine drove through Hewland

gears mounted in an upturned VW gearbox bolted to the back of the engine.

The car's four forward gears were soon upped to five. Bolted on top of

the 'box was a fabricated crossmember carrying the rear suspension top

mounts and also the body. Road & Track wrote, 'the Valielunga incorporates

4-wheel independent suspension in the currently popular GP style'. How

right they were. The front end used one of the few proprietary parts, Triumph

Herald uprights (though some cars seem to have been built with fabricated

items). These pivoted on unequal-length wishbones (the bottom almost twice

the length of the top) with telescopic spring/ damper units, antiroll bar

and rack-and-pinion steering. Disc brakes were fitted to all four wheels.

At the back, a single top link was triangulated by a long radius arm trailing

from the back of the chassis, duplicated at the bottom where a reversed

lower wishbone was used. Again, an anti-roll bar was fitted. Cast uprights

were unique to De Tomaso, as were the attractive cast magnesium 13in wheels

(5.5inch wide front with 145 tires, 6.5inch rear with 165S) and the whole

set-up was rose-jointed.

This, plus the solid mounting of the engine, means the Vallelunga can

never be a refined car, but made its handling more incisive than any other

contemporary road car. If the 1034 pounds claimed is correct, it weighed

only a few pounds more than a Lotus Seven and just two-thirds the weight

of an Elan. Even so, the claimed 130 mph in standard form required a small

pinch of salt.

The car sported a pretty open two-seater aluminum body, which was to

remain a one-off, even though the model was widely reported as being available

for $4315, and even a 45 pound lighter body was quoted. The little car

won races immediately and was shown at the 1963 Turin Show. At the 1964

Show, De Tomaso displayed a coupe version, still bodied in aluminum with

complete flip-up rear body section. The glorious-looking car was clearly

based on the earlier roadster and took shape at the Fissore coachworks.

The Vallelunga coupe was built from early 1964 by Fissore of Savigliano,

but after three (some say five, but just one survivor is known) had been

made De Tomaso transferred the contract to Ghia over whom he had begun

to exercise influence, assuming control by 1967. The Ghia cars were 'productionized'

with a one-piece fiberglass body and were on sale from July '65. Engine

access was now via a lift-up Perspex rear window and a removable plywood

deck lid; arguably this gave somewhere to put luggage, though it might

get hot. There was certainly no luggage space in the front, which housed

merely a beautifully made aluminum fuel tank, the radiator and the hydraulic

master cylinders. The rear bodywork was glassed to a wooden frame which

was then bolted to the rear suspension crossmember.

Overall dimensions were 12ft 7.5in long, 5ft 3in wide and 3ft 6.5in

high, on a 7ft 7in wheelbase. By now the weight had risen to a quoted 1541

lb. - much the same as an Elan. Distribution was very different, however:

claimed to be 47% front, 53% rear. As the engine is so far forward of the

rear wheels this is entirely believable, and with a full fuel tank in the

nose and two passengers, the car must be as near 50/50 as it is possible

to get.

Never one to miss out on an opportunity, at the time the Vallelunga

went into production and pre-dating the Lotus version - De Tomaso was also

offering an uprating package for Ford Consul Cortina GTs. The De Tomaso-Cortina

used the same tuning pack as the Vallelunga with twin 40 DCOE Webers on

appropriate manifolds and a ribbed alloy De Tomaso rocker cover; upgraded

suspension and servo-assisted brakes helped to deal with the claimed maximum

speed of 112 mph.

The one and

only right-hand-drive was ordered by Col Ronnie Hoare, owner of Maranelto

Concessionaires and of F English Ltd of Bournemouth, a major Ford agency.

He was interested in ordering a number of Vallelungas for the UK and installing

engines on arrival. He fitted a Lotus Twin Cam engine complete with dry

sump conversion; the car had apparently been supplied with a Hewland Formula

2 'box which had no provision for reverse gear lubrication.

The one and

only right-hand-drive was ordered by Col Ronnie Hoare, owner of Maranelto

Concessionaires and of F English Ltd of Bournemouth, a major Ford agency.

He was interested in ordering a number of Vallelungas for the UK and installing

engines on arrival. He fitted a Lotus Twin Cam engine complete with dry

sump conversion; the car had apparently been supplied with a Hewland Formula

2 'box which had no provision for reverse gear lubrication.

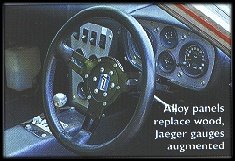

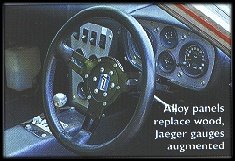

Autosport described the car in November 1965, at which time it

had the twin cam engine and a five-speed gearbox in modified VW casing

(or was it a Colotti box? - sources differ). At the time, no speedometer

was fitted: just tachometer, oil pressure and water temperature. This car

has since been brought up to a full set of appropriate-looking Jaeger instrumentation

(Veglia was used on some cars), with smart alloy panels in the dash and

center console instead of the rather incongruous wood veneer fitted to

most Vallelungas. The door windows slide up and down on this car rather

than winding like most of its brethren. According to De Tomaso's brochure,

the wheel rims were up to 6 inches front, 7 inches rear by now and the

tires, Dunlop SPs, were still 145 front but up to 175 rear; the car now

has 185/60 fronts and 205/60 rears which don't look at all out of place

and lift the cornering limits well beyond normal driving experience.

The car was run on trade plates for a few years before being registered

and sold in 1970. It moved around England for five years before going to

Sweden, where it was rebuilt from parlous condition by Gunnar Brisman.

The previous owner had sold the twin cam and intended to fit a big Yank

V8: thankfully he never did and Gunnar was able to fit an appropriate tuned

Ford 1500 GT unit.

When Duncan persuaded Gunnar to sell, this unique car made it back to

the UK. Though there is a rumor of another Vallelunga, Duncan's is likely

to remain the only example of this most attractive, ingenious and elusive

mid-engined sports car in Britain - more's the pity!

1967 De Tomaso Vallelunga

Timeless beauty that continues to inspire

by John Lamm

From Road & Track Magazine, September 1991

In a past life I worked for another car magazine, a job that involved

a daily drive though the urban clutter called the Hollywood Hills. About

all you could say for that drive is the roads were twisty and the smog

and traffic were light. There were many little roadways into Hollywood,

and while exploring a new route one day I zipped around a corner and stopped

suddenly, for there, parked by the side of the road like a common VW Beetle,

was a De Tomaso Vallelunga. First one I'd ever laid eyes on.

What a beauty, but not in the "zowie" sense. No shock, no electric thrill,

just that wonderful discovery of something quite lovely. It was like finding

a painting that captures your heart in an obscure gallery, or coming across

a Porsche 904 on a back street in Van Nuys, California, parallel parked

among dusty vans and low riders.

On the day of that drive in the early Seventies, the Pantera was still

in production for Ford, so to most auto enthusiasts De Tomaso meant big

V-8s, a rather melodious, strong exhaust note and more than enough power

for most drivers. And yet here was, at least in philosophy, the progenitor

of the Pantera and De Tomaso's Mangusta, a lithe little mid-engine machine

that was inviting rather than daunting in the manner of its big brothers.

If you were to look for a modern equivalent, the logical choice would

be the Mazda Miata. So what does it mean that during the development of

this little Japanese sports car, two of its designers owned Vallelungas?

Tom Matano, who was the design executive of the Miata, and Mark Jordan,

who penned much of the Mazda, both owned the mid-engine De Tomasos during

the time they worked to refine the lines and theme of their sports car.

Tom Matano explains how the Italian GT affected the design of the Japanese

sports car: "Inspiration ... the tin-iness of it ... also some of the flavor

of the Miata. When you sit in the driver's seat of the Vallelunga, you

like to see the peak of the fender ... that's the sort of initial inspiration

we had. We knew that if we were to do a little sports car, we wanted to

make sure it wasn't just a plain-looking miniature Corvette. Luckily enough,

Mark and I both had Vallelungas and knew the car. It was in the back of

our minds when we developed the body's shape." Like the Miata, the Vallelunga

is a small machine. Again, the Miata is a logical comparison ... with the

exception of one important measurement: the weight. The Vallelunga weighs

a scant 1540 lb. (compared with the Miata's 2365), which was possible in

those days before mandated safety equipment like 2.5-mph bumpers and inner-door

beams.

During that era, Automobili De Tomaso was quite prolific. Alessandro

de Tomaso, an expatriate Argentinean, had moved to Italy in the Fifties

and began a racing career that dovetailed with the fortunes of OSCA. When

he ended his relationship with OSCA in the early Sixties, De Tomaso began

a line of rather inventive race cars, ranging from the small formulas to

a sports racer with a cast monocoque chassis to Grand Prix machines ...

cars that suffered most from a lack of commitment by the owner. In 1970,

there was a serious De Tomaso Formula 1 team managed by none other than

Frank Williams. There's a great deal more to Alessandro de Tomaso's automotive

history than the Pantera and his friendship with Lee Iacocca might suggest.

Among those models created by De Tomaso in Modena-where else?- was a

Formula 3 machine from the early Sixties. Although automotive historians

tend to consider the Vallelunga the beginning of the Mangusta-Pantera line,

Santiago de Tomaso, son of Alessandro and keeper of the corporate flame,

ties it more to that F3 car, because it shares much of the same thinking

in suspension design.

The initial Vallelunga was a none-too-lovely open sports car named for

the race track near Rome. The car's chassis was shown at the 1963 Turin

auto show. Early sales brochures featured a side-view drawing of the proposed

"SPIDER a 2 posti" production version, which was designed by Carrozzeria

Fissore and may have some of the basic lines of the coupe, but lacked its

design development and finesse. It would have been a tiger, however, for

while its wheelbase was 91.1 in., its weight was projected at only 1055

lb.

That side of the project came to nothing, but in 1965 the production

grand touring Vallelunga was fact. Chassis specifications of the Vallelunga

are pure race car for the era. Front suspension has unequal-length upper

and lower A-arms, coil spring/shock units and an anti-roll bar. At the

rear is a single upper arm, a reversed lower A-arm, long upper and lower

trailing arms that extend back from the bulkhead, coil spring/shocks and

an anti-roll bar. Note the size of the disc brakes, 9.9-in. diameter in

front and 9.6 at the back. The Dunlop SP tires were unequally sized too,

measuring 145-13 front and 175-13 rear, and mounted in De Tomaso's unique

magnesium wheels.

While the chassis pieces might be relatively exotic, the drivetrain

has rather humble origins. Ford, which would soon get very involved with

De Tomaso and the Pantera, was the source of the powerplant. Known as the

Kent engine, it was a rugged little pushrod 4-cylinder used in all sorts

of Fords around the world. Probably the most exciting application was in

the Cortina GT, where its 1498 cc produced 78 bhp. De Tomaso upped the

power to what the sales brochure claims is 105 bhp at 6500 rpm, with torque

at 128 lb.-ft. at 3600. Compression ratio is 10.3:1, the cylinders fed

by a pair of Weber 40DCOE2 carburetors that look almost as big as the engine

block.

For the gear box, De Tomaso adapted a VW Beetle 4-speed, turned around

for the mid-engine sports car. Though modest at birth, the Ford/VW combination

was a good one, giving the Vallelunga plenty of power and good relilability,

which owners of older Italian cars appreciate.

All this was installed in a backbone chassis of the sort Colin Chapman

had built for the Lotus Elan, albeit turned around for the Vallelunga's

mid-engine placement. The front suspension is attached to the front of

the backbone, while the rear is hooked up to the VW transaxle by way of

a subframe.

Covering everything is a fiberglass body, its design of confused parentage.

While there's no question that Ghia built the cars, no one seems to know

exactly who did the exterior styling ... a shame, because he deserves much

credit.

Tom Matano: "The Vallelunga is quite contemporary. I fell in love with

it when I first saw it in 1965, but looking at it even today, I never get

bored with it. The design has a strength and a life that have survived

the test of time. My yardstick of the durability of a design is if it can

sit in natural scenery and blend in, yet have the strength to come out

of the natural setting, that design will survive longer than a car that

looks good in city scenery. Miata and Vallelunga, I think, are two of those

that will not detract from nature and yet survive on their own. The E-Type

Jaguar is another. I think the latest Ferraris are losing that quality,

but a Daytona put in nature would look fantastic."

Although production Vallelungas had a fiberglass body with a rather

conventional hatchback over the engine compartment, three cars were different.

Built as prototypes, this trio had bodies of aluminum, and a huge rear

body section that rose in one piece, as was common with sports racing cars

of the time.

Although there seems to be some debate over exact numbers, most sources

put the total of Vallelungas built at 58. Fifty of the cars were standard

production models with fiberglass bodies. Then there is the aluminum threesome,

plus five race versions that also have bodies of aluminum.

Six feet tall

is about the limit for Vallelunga drivers. Standing next to the car, you'd

doubt even that, but after doubling over and slipping inside, you're surprised

by just how much room there is, thanks to thin door widths and minimal

seat padding. Everything about the little De Tomaso has a slight, delicate

feel to it. Steering wheel, turn signals and shift lever all let you know

they'd prefer a light touch.

Six feet tall

is about the limit for Vallelunga drivers. Standing next to the car, you'd

doubt even that, but after doubling over and slipping inside, you're surprised

by just how much room there is, thanks to thin door widths and minimal

seat padding. Everything about the little De Tomaso has a slight, delicate

feel to it. Steering wheel, turn signals and shift lever all let you know

they'd prefer a light touch.

To fit all this into such a small package required offsetting the pedals,

turning the driver's lower body just a bit to the right. Tach and speedometer

are large and just ahead of you, flanking that most important of dials,

the oil-pressure gauge. Oil-and-coolant-temperature gauges are at the top

of the center console, while fuel level is at the bottom, out of the way,

which is appropriate because the car gets excellent fuel mileage, even

when being driven very hard. All the gauges are set in a thin wood-veneer

dash.

The engine starts easily and with a lovely sound. Reverse is to the

left and back in the shift gate, but don't force it. Go lightly from gear

to gear. No need to stomp on the clutch. The car feels a great deal like

the formula car that's inside it, with everything reacting quickly and

positively, from the shifter to the steering. Like the Miata, you find

yourself shifting more than necessary just because it feels so good. It's

difficult to imagine taking your little De Tomaso on a drive across the

country, but it's very easy to picture yourself leaving on a Saturday morning

drive on just about any twisty road.

You don't find many of them, but Michael King is a De Tomaso man. He

owns not only the Vallelunga seen here, but also a Mangusta and a pair

of Panteras. King has had the Vallelunga (serial number 807 DT 0141) since

1982. Its first owner was Sergio Delia Malva, who got the car on May 8,

1968. The car stayed in California for two more owners before King, who

lives about 10 minutes from R&T's offices, bought it.

In the end, the Vallelunga seems to share the same fate as many of De

Tomaso's projects from that era; it encountered waning enthusiasm from

the man in charge. There was always something just ahead-Peter Brock's

very exciting 70P race car, then the Mangusta by Giugiaro-and the then-current

project was left behind.

Last updated, Sept 26, 2000

http://www.sonic.net/johnv/car.htm

The one and

only right-hand-drive was ordered by Col Ronnie Hoare, owner of Maranelto

Concessionaires and of F English Ltd of Bournemouth, a major Ford agency.

He was interested in ordering a number of Vallelungas for the UK and installing

engines on arrival. He fitted a Lotus Twin Cam engine complete with dry

sump conversion; the car had apparently been supplied with a Hewland Formula

2 'box which had no provision for reverse gear lubrication.

The one and

only right-hand-drive was ordered by Col Ronnie Hoare, owner of Maranelto

Concessionaires and of F English Ltd of Bournemouth, a major Ford agency.

He was interested in ordering a number of Vallelungas for the UK and installing

engines on arrival. He fitted a Lotus Twin Cam engine complete with dry

sump conversion; the car had apparently been supplied with a Hewland Formula

2 'box which had no provision for reverse gear lubrication.

Six feet tall

is about the limit for Vallelunga drivers. Standing next to the car, you'd

doubt even that, but after doubling over and slipping inside, you're surprised

by just how much room there is, thanks to thin door widths and minimal

seat padding. Everything about the little De Tomaso has a slight, delicate

feel to it. Steering wheel, turn signals and shift lever all let you know

they'd prefer a light touch.

Six feet tall

is about the limit for Vallelunga drivers. Standing next to the car, you'd

doubt even that, but after doubling over and slipping inside, you're surprised

by just how much room there is, thanks to thin door widths and minimal

seat padding. Everything about the little De Tomaso has a slight, delicate

feel to it. Steering wheel, turn signals and shift lever all let you know

they'd prefer a light touch.