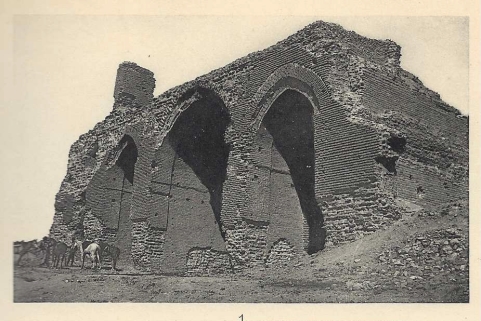

Figure 1. The Bāb al-ʿĀmmah (Viollet, “Un palais musulman”, pl. 4,1).

Table of Contents

The Dār al-ʿĀmmah in Samarra, built beginning in 221/836 and occupied from 223/838 until about 279/892, is unusual in many ways. As Ernst Herzfeld wrote of its plan, there is nothing like it (“nirgends ihresgleichen”).1

Our knowledge of the Dār al-ʿĀmmah and of Samarra as a whole has been much expanded by the publication in 2015 by Alastair Northedge and Derek Kennet of Archaeological Atlas of Samarra, which provides the visual and analytical foundation for Northedge's earlier and excellent The Historical Topography of Samarra. These works, grouped under the series title Samarra Studies, are, like Northedge's other works, clearly written, well proofread, and illustrated with informative maps and plans tailored to the topics under discussion.2 They lay out the results of a great deal of topographic investigation and make it possible to assemble plans and aerial photographs of the entire palace precinct (the Dār al-Khilāfah) and adjacent areas.3 For the Dār al-ʿĀmmah they are complemented by Matthew Saba's article “A Restricted Gaze: The Ornament of the Main Caliphal Palace of Samarra”, which deals carefully with the results of Herzfeld's excavations, particularly the ornament of the east end of the building.4

In this article I discuss the western approach to the Dār al-ʿĀmmah, particularly the grand stairway in front of the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah and the square space below it, which has been interpreted as a basin, using the historical sources gathered by Northedge and linking to material in the Smithsonian Institution's Herzfeld Archive.5

Figure 1. The Bāb al-ʿĀmmah (Viollet, “Un palais musulman”, pl. 4,1). |

In Herzfeld's manuscript plan of the caliphal palaces (FSA A.06 05.1016) and his beautifully drawn reconstructions of the Dār al-ʿĀmmah's western approach a triple īwān-hall, the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah, looks out over a shallow terrace, beyond which a stairway sixty m. wide and long descends seventeen m. to a basin 127 m. square surrounded by arcades.6 (Of the drawings, I like FSA A.06 05.1101 best, but there are others, not all by Herzfeld: FSA A.06 05.1039, FSA A.06 05.1102, and FSA A.06 05.1034.) The Shāriʿ al-Aʿẓam, apparently the only road passing by the caliphal palaces, separates the basin and two rectangular gardens north and south of it from an immense garden to the west, next to the Tigris.

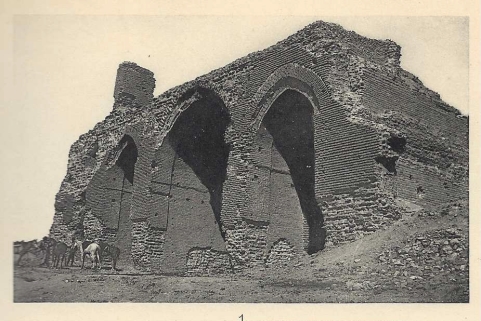

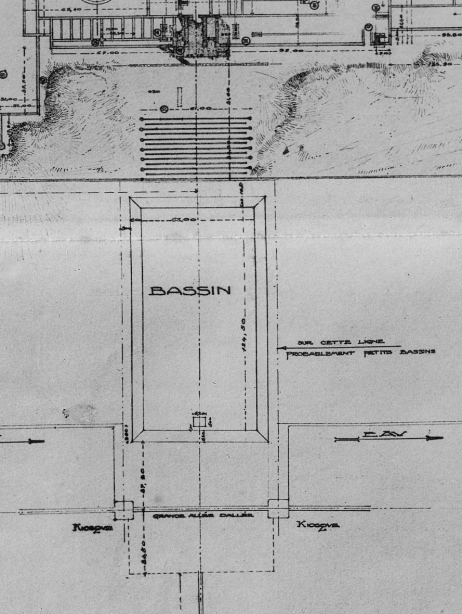

Figure 2. The basin (Viollet, “Un palais musulman”, pl. 1, detail). |

Henri Viollet excavated at the Dār al-ʿĀmmah in 1910 and published his results very briefly in 1911.7 He thought the basin received water from a cascade down what Herzfeld interpreted as a stairway:

Pour terminer la description de cet ensemble, il ne me reste qu'à signaler les grandes pièces d'eau, peu profondes, qui s'étendaient au pied de la falaise, et dans lesquelles venait mourir une cascade qui occupait tout le front de trois arcs [of the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah]. (Une fouille pratiquée en R' a démontré que des murs de soutènements de 0 m. 80 d'épaisseur occupaient les 14 tranchées encore visibles parallèles et en gradins.) Un grand bassin rectangulaire, de 124 m. 50 de long sur 62 mètres de large, recevait les eaux de la cascade. Il était bordé d'une plate-bande, sur laquelle on remarque à intervalles réguliers une série continue de trous peu profonds: petits bassins secondaires ou motifs décoratifs (l'absence de traces de fondation ne peut faire admettre que ces deux hypothèses). A l'extrémité de ce lac, dans son axe, un canal qui conduit à l'ancien lit du fleuve, distant du pied de la falaise de près de 500 mètres, aboutit à un petit édicule, abri-fontaine, qui se mirait dans les eaux du Tigre. De nombreux freagments de marbre et de briques de pavage ont été trouvés sur les bords de ces divers bassins.

Ces jeux d'eau au murmure léger, miroitant au soleil couchant dans la paix des beaux soirs d'Orient, devaient être d'un grand effect, vus de la terrasse qui bordait la façade.

Le Khalife pouvait oublier, devant ce beau spectacle de la nature, dont les Orientaux sont si friands, les soucis du pouvoir.

The circled letters on Viollet's plan are mostly illegible, but I think R' must refer to the circled letter at the head of the stairway, indicating that spot itself and not the narrow rectangle above and to the right of it. If so, the dotted line that extends to either side of of the circled letter marks the inferred line of the supporting wall Viollet found, and the twelve parallel lines below (west) of it are restorations of similar walls in the visible “tranches”, or trenches. His reference to fourteen such trenches is at odds with his plan, but perhaps he counted twelve visible trenches and inferred two more, based on the distance between his excavation and the uppermost trench. The small circles on the ends of alternate parallel lines are unexplained.

Figure 3. Air survey photograph of the Dār al-ʿĀmmah, University College London Library, Special Collections (Box 234 IOA Collection). |

Figure 4. Detail of Figure 3. |

An oblique aerial photograph taken in 1936 or 1937 and first published by Northedge shows the terrace and stairway.8 It is clear in this view that there is a rising ridged area above the basin, corresponding to Viollet's trenches, and a smooth slope above that. Where the smooth slope meets the level terrace is not clear from the photograph. Viollet's plan reflects the section he published in an earlier article (“Description du palais de al-Moutasim”, pl. 12), in showing a fairly deep terrace.

I have found four photographs of the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah by Herzfeld, which appear to show the stairway in much the same condition in his (and Viollet's) day as when the oblique aerial photograph was taken (FSA A.6 04.PF.22.001, FSA A.6 04.PF.22.002, FSA A.6 04.PF.22.004, and FSA A.06 04.PF.23.145). Of these photographs, FSA A.6 04.PF.22.002 best shows the angle of the smooth area, while FSA A.06 04.PF.23.145 shows that it was strewn with rubble.

Herzeld's reconstruction, in his manuscript plan, shows the boundary between the ridged and smooth areas and continues the stairway up through the lower part of the smooth area, leaving a shallow terrace. In two different impressionistic birds-eye reconstructions (“Description du palais de al-Moutasim”, pl. 13 and 14) Viollet made the terrace shallower than in his plan. Herzfeld's photographs appear to support a shallow rather than deep terrace, and I follow his judgement. I estimate that there might have been about eighteen supporting walls.9

If Viollet found supporting walls under the smooth area, it must have been man-made rather than natural, although its original surface may lie below what is visible in photographs, buried by debris, including mud-brick melt from the palace. The ridged area seems to be some combination of masonry and shaping of the terrain, which was left in its disturbed condition by brick robbing that did not extend to the smooth area.

K.A.C. Creswell, following Herzfeld and Viollet, observed that “[John] Ross, when he was here in 1834, saw ‘an inclined platform resting on arches’ leading down to the lower ground”. 10

The number of steps Herzfeld drew in the stairway varied. By my count there are fifty-four steps in the printed version of Herzfeld's plan, not counting the terrace or the flat space below the stairway (I have not been able to count the steps in the online scan of the manuscript plan). The steps in the reconstruction drawing FSA A.06 05.1101, which appear to have level treads, are rendered more impressionistically; I count thirty-five steps. Clearly, Herzfeld drew the steps appropriately for visual effect and did not attempt a concrete reconstruction of their number.

The likely number of steps can be estimated by working from the height of the terrace above the basin, about seventeen m. The steps of modern domestic stairs are roughly twenty cm. high. It would take eighty-five such steps to carry from the basin to the terrace. As the stairway is about sixty m. deep, such stairs would be about seventy cm. deep.

Figure 5. Rome, Cordonata Capitolina. |

Figure 6. Rome, Cordonata Capitolina. |

But a better solution would have been to ramp the treads, as in the sixteenth century stairway leading to the Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome (the Cordonata Capitolina), which is a bit deeper but approximately the same height, and has nineteen steps. The rise of the front edge of each ramped step can be small given its depth, and such a ramped stairway can be ascended by animals easily. That method of construction would accord with the “inclined platform” Ross reported.

Charming as it is, Viollet's interpretation of the stairway and the basin must be discounted.

I have not found any ground-level photograph that shows the basin clearly. It has been flooded by the barrage built in the early nineteen-fifties and is not visible now.11 Viollet's dimensions for it are clearly wrong, as the aerial photographs Northedge and Kennet published, as well as the oblique aerial view, show it to be square or squarish, which is also as Herzfeld drew it after he had investigated the site in detail.12 The length Viollet reported for the basin is close to Herzfeld's measurement, 127 m. square, but something is wrong with the width. It seems that Viollet simply made a mistake about the width of the basin in drawing up his plan, perhaps misled by field notes: the width he arrived at is just half of the length he measured, so it was probably derived from a measurement taken from the centerline of the basin, not across its entire width.13

The aerial photographs also show low ruins surrounding the basin (Viollet's “plate-bande”, or border). Perhaps they are the remains of a heavy wall or the arcade that Herzfeld reconstructed. The oblique aerial view, taken in March, shows vegetation in part of the basin, which indicates that it was deep enough to hold some rainwater. But that means only that the level of the square area was lower than that of the ruins of the surrounding structure.

Herzfeld seems never to have considered the area at the foot of the stairway as other than a basin. He did not discuss it in Samarra, Aufnahmen und Untersuchungen zur islamischen Archäeologie, of 1907, nor in Archäologische Reise im Euphrat- und Tigris-Gebiet, v. 1, of 1911,14 but in “Mitteilungen über die Arbeiten der zweiten Kampagne von Samarra”, of 1914, he called it a Bassin.15

Neither Viollet nor Herzfeld published any rationale for interpreting this square space as a basin, nor any graphic evidence for it. It is not mentioned in historical sources.

Dominique Sourdel, who thought there should have been a formal entry to the Dār al-ʿĀmmah on its east side, observed that the stairway and basin “preclude the deployment of troops indispensible for receptions”, but did not go so far as to reject the interpretation of the area as a basin.16

But the basin can hardly have been a basin, as can be seen from the historical sources so conveniently assembled by Northedge, which describe public spectacles, including various beatings, executions, and corpse desecrations that occurred at the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah, as well as an acclamation there that was interrupted by a pitched battle.17 It must have been a courtyard.

A prime location for executions was the Khashabah Bābak, where the rebel Bābak was executed. It was well to the south of the Dār al-Khilāfah, somewhat north of the main prison,18 and Bābak was executed there in 223/838, the year ʿAbbāsid notables first moved to newly built Samarra.19 Perhaps the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah was not yet in condition to serve as the venue for this event, although Bābak was taken to the Dār al-ʿĀmmah earlier, when he arrived in Samarra (the people “stood in a line” for a long distance for this event, presumably along the Shāriʿ al-Aʿẓam). As Khashabah Bābak was later used for other executions it is more likely that the spot was chosen for his execution for its proximity to the prison. I have not noticed historical sources recording multiple public punishments or executions or desecration of corpses in Samarra other than at the Khashabah Bābak and the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah, in Northedge's collection or elsewhere. But there was a public flogging in al-Ḥayr,20 and I have not made a special search.

In 226/840–41 the general Al-Afshīn was crucified postmortem “on the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah, so that the people should see him, then [his body] was thrown out with his cross at the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah. The body was burnt, and the ashes taken and thrown in the Tigris.”

In 227/842 a victorious general brought a captive to Samarra and “stopped at Bāb al-ʿĀmma.”

In 235/849–50 “a man named Maḥmūd b. al-Faraj al-Naysābūrī appeared in Sāmarrā. He claimed to be Dhū al-Qarnayn. He had with him twenty-seven men in the vicinity of Khashabat Bābak. Two of his companions appeared at the Public Gate [Bāb al-ʿĀmmah].”21 It is not stated what these two men did, but Maḥmūd and his followers were arrested, interrogated, and flogged; Maḥmūd was then taken to the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah, where he recanted (obviously in front of a witnessing crowd).

In 239/853–54 one man was “killed at Bāb al-ʿĀmma” and another, separately, had his head “cut off at Bāb al-ʿĀmma and [he was] crucified”.

In 241/855–56

[Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh] al-Qummī departed [from upper Egypt] with ʿAlī Bābā [the king of the Bujah, whom he had defeated] for the gate of al-Mutawakkil, and arrived there at the end of 241. He attired this ʿAlī Bābā with a silk brocade-lined robe and a black turban and covered his camel with a brocaded saddle and brocade horse cloths. At the Bāb al-ʿĀmma, along with a group of the Bujja, were stationed about 70 pages, upon saddled camels, carrying their lances, on whose tips were the heads of their [Bujah] warriors who had been killed by al-Qummī.

The camels might have been lined up on the two sides of the ramped stairway or in the courtyard below. Seventy camels could have been lined up on the terrace, although it might have been a tight fit.

In 242/857 Al-Mutawakkil had an apostate named ʿAṭārid executed: “his head was cut off on 2 Shawwāl, and he was burnt at Bāb al-Āmma”.

In 250/864–65 al-Mustaʿīn had the head of an ʿAlid rebel displayed at the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah “for an hour … and the people gathered in number” according to Abū Bakr al-Ṣūlī. Abū Jaʿfar al-Ṭabarī wrote: “The head was displayed at the Public Gate [Bāb al-ʿĀmmah] in Sāmarrā, where the people gathered to see it. They grew in numbers and complained”.22

In 255/869 Ṣāliḥ b. Waṣīf, one of the most powerful Turkish leaders, was extorting money from the wazīr and a member of the court who had stolen from the treasury. They were brought to the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah and flogged. Ṣāliḥ “sat in al-Dār and entrusted their beating” to someone else, who directed two actual floggers.23

In 256/870 the head of Ṣāliḥ b. Waṣīf was paraded around town on a pike and then displayed at the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah for an hour on three successive days, replacing the head of Bughā the Younger.24

In 258/871–72 fourteen Zanj rebels were beheaded at the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah.

Later in 258/871–72 a man was beaten at the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah.

In 259/872–73 the Christian secretary of a rebellious governor was flogged at the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah.

Where did these spectacles take place and where did people stand to watch such spectacles?

“At the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah” need not mean immediately in front of the triple īwān-hall on the terrace, but if these public spectacles were not held in one of the gardens the only other location for them, assuming a basin, is at foot of the stairway.

If the crowd gathered along the road west of the courtyard its view of anything would probably have been blocked by a wall. If it stood in Herzfeld's arcades around Viollet's basin it could hardly have seen anything happening on the terrace except from the west side of the basin, which would have been nearly two hundred m. away, and over a football field (including end zones) away even from the foot of the stairway. And there is hardly any room at the foot of the stairway to stage an event.

While it was probably not a functional requirement for its architect that the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah have a place for burning corpses, it would have been one that the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah be suited to public spectacle. It was not, if the square space below the stairway was a basin.

Instead, the crowd must have assembled in the courtyard to watch something taking place on the terrace or in the courtyard itself.

My conclusion that the basin was really a courtyard is supported by al-Ṭabarī's account of an acclamation. It seems to be the only account of such an event at the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah, but on that score it is incomplete, as the acclamation was interrupted by a battle.

In 248/862, two days after the caliph al-Muntaṣir, a son of al-Mutawakkil, died a group of Turkish leaders arranged an acclamation for their choice of successor, al-Mustaʿīn, which was attacked by partisans of al-Muʿtazz, also a son of al-Mutawakkil and his formal heir.25

Abū al-ʿAbbās [al-Mustaʿīn] went to the Dār al-ʿĀmmah, by way of the ʿUmarī [Palace],26 between the gardens [bayn al-bustānayn]. They had dressed him in long robes and in the caliphal raiment. Ibrāhīm b. Isḥāq carried the spear (ḥarbah) in front of him; this took place before sunrise. Wājin al-Ushrūsanī arrived at the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah by way of the main thoroughfare leading to the public treasury (bayt al-māl) [Northedge: reached the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah from the direction of the Avenue [shāriʿ] by [ʿala] the Bayt al-Māl].27 After arranging his troops in two lines, he took his position in line together with the notables among his men. Present at al-Dār were the men of rank (aṣhāb al-marātib). These included the sons of al-Mutawakkil, the ʿAbbāsids, the Ṭālibids and others of stature. While they were stationed in this manner—an hour and a half of the day had already passed—shouting was heard from the direction of [the avenue and the market, al-shāriʿ wa al-sūq28]. Suddenly, there were fifty horsemen of the Shākiriyyah … accompanied by a group of Ṭabariyyah cavalry and mixed forces (akhlāṭ al-nās). They were joined by the hotheads and the rabble from the market, amounting to a group of about one thousand men. Drawing their weapons, they shouted “Victory to Muʿtazz” … and charged the two lines of the Ushrūsaniyyah formed by Wājin. A great melee ensued, and the men collided with one another. Some of the Mubayyiḍah guarding the Public Gate (Bāb al-ʿĀmmah) broke rank and joined the Shākiriyyah, thus increasing their number. At this the Maghāribah and the Ushrūsaniyyah attacked, and, routing the rebels, they forced them onto the great road (darb) named after Zurāfah and ʿAzzūn. A group of them charged the followers of al-Muʿtazz, and, having defeated them, they pursued them to the residence of ʿAzzūn b. Ismaʿīl's brother where the latter held a narrow part of the road. Al-Muʿtazz's followers held their ground there, whereupon the Ushrūsaniyyah fired arrows at some of them and engaged them with swords. As the battle raged between them, the followers of al-Muʿtazz and the rabble proclaimed “God is Great!” Many of the protagonists fell, slain, as the battle continued until the third hour of the day. The Turks then departed, having rendered allegiance to Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. al-Muʿtaṣim [al-Mustaʿīn]. They left (by the road that runs) beside the ʿUmarī (Palace) and the gardens. Before leaving, the mawlās obtained the oath of allegiance from all those present at the Dār al-ʿĀmmah, including, among others, the Hāshimites and the men of rank. Al-Mustaʿīn departed by way of the Public Gate for the Hārūnī (palace) [on the west bank] where he spent the night.29

The troops commanded by Wājin al-Ushrūsanī were drawn up in two lines, along with notables (who may have been lined up separately). Hilāl al-Ṣābi' described the protocol for later caliphal public receptions in Baghdad. After much greeting of the caliph by officials and notables who then stand near the throne, “when the general permission is given, the soldiers enter and stand in two lines between two ropes stretched in the al-Salām Courtyard.”30 This parallelism proves nothing in itself, but it is clear that a courtyard was necessary for later ʿAbbāsid public reception. How the ceremony of acclamation would have involved the two lines of troops is unknown; perhaps notables, even the two sons of al-Mutawakkil, al-Muʿtazz and al-Muʿayyad, were to arrive and proceed to the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah between them.

Several routes of access to the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah are mentioned: by way of the Qaṣr al-ʿUmarī and the gardens; from the direction of the avenue by the bayt al-māl; and possibly a great darb named after Zurāfah and ʿAzzūn, through which the insurgents were repelled. Al-Ṭabarī must have felt this information was significant, but I can only guess at why: all of these routes lie south of the Dār al-ʿĀmmah and they ran (somehow) through a neighborhood of the residences of the caliphate's highest officials.31 These routes would have been heavily guarded. The mob must have arrived via the public Shāriʿ al-Aʿẓam.

I am inclined to deflate the numbers of men reported by medieval sources, especially a round number such as one thousand. The size of the pro-Mustaʿīn force is not reported, but as military commanders intending to proclaim a new caliph would likely provide a substantial force and it overcame the opposition, it was likely in the hundreds.

So there was an engagement of some hundreds of horsemen and irregulars in front of the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah. Part of the action may have moved to adjacent areas, such as the narrow garden south of the square space below the stairway, but the insurgents initially attacked the two lines of Ushrūsanīyah drawn up before the gate of the palace. This must have taken place been either on the terrace, where there is no space for the numbers mentioned, or below it. A battle on the stairway is conceivable, but it is hard to imagine the mob storming into an arcade (or uncovered passageway) built around a basin and getting that far in numbers sufficient to matter.

The partisans of al-Muʿtazz must have stormed into the courtyard from the Shāriʿ al-Aʿẓam through whatever gates separated the two spaces and attacked troops drawn up in the courtyard.

The Bāb al-ʿĀmmah and the terrace, stairway, courtyard, and garden in front of it comprise a composition unique in early ʿAbbāsid palace architecture. There was no possibility of creating such a stairway in flat Raqqah or low-lying Baghdad and no other such stairway appears to have been built in Samarra. The combination of tall īwān-hall, here tripled, and immense courtyard or garden is standard. But the insertion of the stairway and terrace changes the effect by elevating the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah above those who came to watch a public spectacle or enter the palace where the caliphate was administered and by distancing the palace from even its entry courtyard.32

What made the stairway both necessary and possible is that the Shāriʿ al-Aʿẓam descended from the bluff into the flood plain north and south of the Dār al-Khilāfah, where it was channeled between what must have been north-south walls west of the courtyard.33

I imagine that the earliest road or track on the east bank of the Tigris along this stretch ran along the top of the bluff, and that at some point it was displaced to the flood plain. Perhaps al-Muʿtaṣim's architects arranged the displacement of the bluff-top road. I know of no precedent for such a change.

Alternatively, if the bluff-top road already ran through the flood plain the site itself could have suggested something of the ʿAbbāsid layout. At the time Samarra was planned a monastery and a garden at the site of the Dār al-ʿĀmmah were purchased from its monks.34 The garden seems likely to have occupied the fertile ground on which the courtyard and garden were built. The monks must have had a path—or stairway—down the slope below the bluff to the garden.

If what was to become the Shāriʿ al-Aʿẓam already ran below the bluff when al-Muʿtaṣim traversed it during a hunting trip, or when al-Muʿtaṣim's architects were choosing sites for palaces,35 they may have seen, from the viewpoint of a future visitor, a hint of the approach to the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah that al-Muʿtaṣim built there.

Following the construction of the Dār al-ʿĀmmah the Shāriʿ al-Aʿẓam ran through its grounds, posing problems of security and traffic management. It was necessary to control the heterogeneous traffic on the avenue and prevent the public from entering either the courtyard or the garden to its west without permission. It was also necessary to make it convenient for authorized persons, including large parties of them, to cross from the courtyard to the garden and vice versa, without disruption of or from the traffic on the grand avenue.

I believe the only plausible solution would have been to depress the avenue and construct bridges across it. Below, I show two examples of this approach from Italy.

Figure 7. Parchi di Nervi, Via Serra Gropallo. |

The Parchi di Nervi, in what is now eastern Genoa, is a large botanical park dotted with museums. The Via Serra Gropallo crosses it, running from the Via Aldo Casotti, on the landward side of the park, under the railroad tracks on its seaward side, to the Passeggiata Anita Garibaldi, which runs along the cliffs next to the Ligurian Sea. It is depressed deeply; footbridges across it connect the sections of the park it divides.

Figure 8. Rome, Via della Pilotta. |  Figure 9. Rome, Via della Pilotta from the gardens of the Palazzo Colonna. |

A variation of the depressed road is the Via della Pilotta in Rome. It is at the same level as the other streets in its immediate area to the north, west, and south. It separates the Palazzo Colonna on its west side from the Colonna gardens, which climb the slope of the Quirinal Hill to the east, starting from a level well above the street. Viaducts across the Via della Pilotta connect the lowest level of the gardens directly to the second story of the palace.

While we cannot know how the Dār al-ʿĀmmah's courtyard was delimited, nor how access to it from the level of the garden was controlled, one or the other of the Italian depressed road solutions must have been implemented.

This article has been revised (in December 2017) to add a reference to Herzfeld's pencil plan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in footnote 6, to add an article to list of Northedge's publications in footnote 2, and to modify my observation about public punishments elsewhere than at the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah. It was further revised (in March 2023) to add illustrations of the Cordonata Capitolina and include the final section on the handling of the Shāriʿ al-Aʿẓam.

1. For the date, Alastair Northedge, Historical Topography, pp. 99, 135. I follow Northedge's identification of the Dār al-ʿĀmmah as the southern of the two palaces that were formerly called the Jauṣaq al-Khāqānī, and the Jauṣaq al-Khāqānī as the northern palace.

Herzfeld's characterization, “Dieser Komposition, die wohl nirgends ihresgleichen hat, entsprach die Pracht der Ausstattung des Palastes”, is in “Mitteilungen über die Arbeiten der zweiten Kampagne von Samarra”, Der Islam, v. 5, 1914, pp. 196–204, p. 202.

2. Northedge's principal publications on Samarra are:

“The Racecourses at Sāmarrā'”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, v. 53, 1990, pp. 31–56.

“Creswell, Herzfeld, and Samarra”, Muqarnas, v. 8, 1991, pp. 74–93.

“An Interpretation of the Palace of the Caliph at Samarra (Dar al-Khilafa or Jawsaq al-Khāqāni)”, Ars Orientalis, v. 23, 1993, pp. 143–71, cited here as “Interpretation”.

“The Jaʿfarī Palace of al-Mutawakkil”, Damaszener Mitteilungen, v. 11, 1999, pp. 345–63.

The Historical Topography of Samarra, London, 2005, cited here as Historical Topography.

With Derek Kennet, Archaeological Atlas of Samarra, 3 v., London, 2015, cited here as Archaeological Atlas. The 3 v. are numbered as though parts of v. 2 of Samarra Studies, of which Historical Topography is counted as v. 1; I refer to them as parts here. Part 3 contains sections of aerial photograph mosaics and corresponding plans and “unit keys”, each termed a “map”. Each set of three maps is termed a “sheet”.

3. Historical Topography, fig. 44, 53, and 54; Archaeological Atlas, pt. 3, sheets 201 (maps 32–34), 111 (maps 38–40), and 112 (maps 41–43).

4. Matthew D. Saba, “A Restricted Gaze: The Ornament of the Main Caliphal Palace of Samarra”, Muqarnas, v. 32, 2015, pp. 155–95.

5. All the links here work at the moment, but will surely break when the Smithsonian redesigns its web site, which inevitably it will do. The text of each link contains the Smithsonian's “local identifier” for the item (which includes spaces). These identifiers can be used to locate the item and its catalogue entry by searching.

6. The manuscript plan, in ink, is the basis for the plan published by K.A.C. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture, 2 v., Oxford, 1940, v. 2, fig. 194, but is fuller. It is catalogued as a watercolor. The Metropolitan Museum of Art preserves a pencil plan by Herzfeld, in two parts, from which the ink plan may have been developed. It is catalogued under the “identifer” eeh 1628.1-2 (including a space) and can be found online here.

In the approved translation by Creswell, op. cit., p. 232, of Herzfeld's “Mitteilungen über die Arbeiten der zweiten Kampagne von Samarra”, Der Islam, v. 5, 1914, pp. 196–204:

The scheme of the immense lay-out was revealed step by step and became intelligible only when it was found, during the excavation and laying bare of the plan of the Palace and the survey of the town, that the immense complex had only one entrance in the middle of the west side, namely the gateway ruin still well preserved to-day, the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah, and that it was therefore oriented in the opposite direction to the Balkuwārā Palace and belonged to a type fundamentally different from it.

The Tigris once washed the whole west and south-west side of the low-lying garden. The “Great Street” coming from the south touched the palace wall where it strikes, at an acute angle, against the high Tertiary beach on the south. There lay the Bāb al-Nizāla, the “Dismounting Gate”. A road about 600 m. long led thence through the garden to the great basin, measuring 127 m. square, from which a great flight of steps, 60 m. broad and about the same in length, gently ascended to the terrace, 17 m. high [T.A.: zu der 17 m hohen Terrasse], in front of the Bāb al-ʿĀmma.

7. “Fouilles à Samara en Mésopotamie, un palais musulman du IXe siècle”, Mémoires de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, v. 12, pt. 2, published as an extract dated 1911, the text paginated pp. 3–35, and in the Mémoires, pp. 685–713. The quotation above is from p. 16 (698). Also in that volume, pt. 2, which is dated 1913, is his article “Description du palais de al-Moutasim fils d'Haroun-al-Raschid à Samara et de quelques monuments arabes peu connus de la Mésopotamie”, pp. 567–94. Both articles are followed by unpaginated plates. “Description du palais de al-Moutasim” seems to document his journey through Mesopotamia in 1907–08 and “Fouilles a Samara. Ruines du palais d'al-Moutasim” his excavations in 1910. His visit to Samarra in 1908 is dated in “Description du palais de al-Moutasim”, p. 577, and the date of his excavations is provided in “Fouilles a Samara. Ruines du palais d'al-Moutasim”, Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, v. 55, 1911, pp. 275–86, p. 276.

8. “Interpretation”, fig. 5; Northedge's caption dates it 1936, following the catalogue information of the University College London Library, but the date written in the upper right-hand corner is 23.3.37. I thank Robert J. Winckworth for providing me a scan of this photograph in TIFF format. I have converted it to JPEG format and adjusted the detail from it digitally by sharpening it slightly and slightly increasing the contrast.

9. Seton Lloyd, “Jausaq al-Khaqani at Samarra: A New Reconstruction”, Iraq, v. 10, 1948, pp. 73–80, p. 75, followed one of these reconstructions (pl. 14). Neither shows the basin.

10. John Ross, “ A Journey from Baghdád to the Ruins of Opis, and the Median Wall, in 1834”, Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, v. 11, 1841, pp. 121–36, p. 129. For this article see https://archive.org/details/jstor-1797639.

Seton Lloyd, op. cit., p. 75, thought Ross's observation was “a confusion with the three arches supporting a section of the terrace itself, whose foundations Herzfeld excavated”. They are shown in Lloyd's pl. 9 north of the terrace and on Herzfeld's plan.

11. Historical Topography, pp. 37, 133.

12. Northedge gave its dimensions as 115 by 130 m., “Interpretation”, p. 145, but did not state how he obtained those measurements. Herzfeld's first, gridded plan of the Dār al-ʿĀmmah, FSA A.06 05.1018, was drawn from Viollet's plan and shows the basin in Viollet's proportions. The relevant aerial photomontage, FSA A.06 07.04.03.02, does not show the stairway in useful detail and does not cover the basin.

13. Some other elements of the two plans correspond. A small rectangle in the middle of the west side of the basin in Viollet's plan is matched on Herzeld's plan. The “trous peu profonds” he wrote of seem to be matched on the plan by the label “sur cette ligne probablement petits bassins”, but they are not drawn. On the south side, they may be visible in the oblique aerial photograph as a series of disturbances. Herzfeld neither reported nor drew anything of the sort. The northern “Kiosque” beyond the basin on Viollet's plan is matched by a feature on Herzfeld's manuscript plan.

Part of the canal leading to the “petit édicule” that Viollet drew appears on Herzfeld's manuscript plan, with the structure at its far end, although neither Viollet nor Herzfeld explained where its water came from.

14. With Friedrich Sarre, 4 v., Berlin, 1911–20. His party did not visit the Dār al-ʿĀmmah in 1908 (v. 1, p. 87).

15. Der Islam, v. 5, 1914, pp. 196–204, p. 199.

Léon de Beylié, “L'architecture des Abbassides au IXe siècle”, Revue archéologique, ser. 4, v. 10, 1907, pp. 1–18, did not discuss anything in front of the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah, nor did he illustrate or plan the area. Gertrude Bell wrote nothing useful about the Dār al-Khilāfah in either Amurath to Amurath, of 1911, or Palace and Mosque at Ukhaidir, of 1914.

16. “Questions de cérémonial ʿabbaside”, Revue des Études Islamiques, v. 28, 1960, pp. 121–48, p. 127.

17. Historical Topography, pp. 278–80. I have supplemented Northedge's excerpts as noted in footnotes below, without adding any sources.

18. Ibid., fig. 45.

19. Ibid., p. 99.

20. Ibid., p. 304.

21. The History of al-Ṭabarī, v. 34, trans. Joel L. Kramer, p. 95.

22. The History of al-Ṭabarī, v. 35, trans. George Saliba, p. 19.

23. The History of al-Ṭabarī, v. 36, trans. David Waines, p. 11. This incident was discussed by Matthew Gordon, The Breaking of a Thousand Spears, Albany, 2001, pp. 101–02.

24. The History of al-Ṭabarī, v. 36, trans. David Waines, p. 90.

25. The History of al-Ṭabarī, v. 35, trans. George Saliba, pp. 1–2.

26. Saliba, the translator, invented an ʿUmarī Road that I suppress here; the text reads min ṭarīq al-ʿUmarī. The Qaṣr al-ʿUmarī is known from historical sources.

27. Historical Topography, p. 279.

28. Saliba translated these words as “the main thoroughfare and the markets”.

29. The History of al-Ṭabarī, v. 35, trans. George Saliba, pp. 2–4. Words in square brackets are my interpolations. I have silently suppressed the mistranslation of Dār al-ʿĀmmah as “Public Audience Hall”.

30. Al-Ṣābi', (d. 448/1056–57), Rusūm Dār al-Khilāfah, trans. Elie A. Salem as Rusūm Dār al-Khilāfah (The Rules and Regulations of the ʿAbbāsid Court), Beirut, 1977, pp. 63–64.

31. Northedge located the Qaṣr al-ʿUmarī immediately outside the garden south of the Dār al-Khilāfah, at H181, and the bayt al-māl somewhere immediately south of the Dār al-ʿĀmmah (ibid., pp. 121, 141, and fig. 54).

32. The historical sources show clearly that the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah was the principal entry to the Dār al-ʿĀmmah. Five other entrances are named, though they are mentioned far less frequently than the Bāb al-ʿĀmmah. Northedge discussed them all, and concluded that Bāb al-Bustān and Bāb Ītākh are two names for the same gate, “at the entrance to the prolongation of the avenue [Shāriʿ Abī Aḥmad] inside the palace complex”, and that the Bāb al-Maṣāff (perhaps also called the Bāb al-Nazālah) was the inner gate, located toward the east end of the Great Esplanade of the Dār al-ʿĀmmah (ibid., pp. 140–41). Herzfeld excavated this gate. His excavation seems not have been written up, but the catalogue entries for the photographs FSA A.6 04.PF.22.123, FSA A.6 04.PF.22.124, FSA A.6 04.PF.22.125, FSA A.6 04.PF.22.126, and FSA A.6 04.PF.22.127 identify them (with some variation, parenthetical glosses omitted) as “Excavation of Samarra: Palace of the Caliph, Great Courtyard (Great Esplanade), South Wall: View of Entrance Gate” on the basis of German captions “transcribed” (translated?) by Joseph Upton.

There was also a Bāb al-Wazīrī and a Bāb al-Sumaydaʿ. Northedge wrote that the “Bāb al-Wazīrī should logically be the gate which led to al-Wazīrī”, one of the palaces constructed at the founding of Samarra, which he located to the north (ibid., pp. 146–48 and fig. 56). Perhaps it was the entrance from the terrace north of the triple īwān-hall that leads to a courtyard with a large circular feature in the northwest of the Dār al-ʿĀmmah. This entrance is shown on Northedge's plan but not on Herzfeld's, so I assume its existence was established by Iraqi archaeological work. There should be another such entrance south of the triple īwān-hall. Northedge associated the Bāb al-Sumaydaʿ with the Jauṣaq al-Khāqānī (ibid., p. 141).

33. Ibid., pp. 102–04, 116, 140–41, fig. 44, 53. Herzfeld's plan contains hints that there were gates across the avenue along this stretch; cf. Historical Topography, fig. 55.

34. The monastery and garden were bought for al-Muʿtaṣim by Abū'l-Wazīr Aḥmad b. Khālid (ibid., p. 97). Just where the monastery was is impossible to determine. Reportedly it became the bayt al-māl, but that structure can be localized only hazily. See Historical Topography, p. 141, for Northedge's treatment. But it was somewhere under or near the Dār al-ʿĀmmah.

35. Ibid., pp. 98, 268.