|

September 2, 2002

Farmington, Maine

"Clear, visibility 70 miles, light winds, temperatures in the 50s."

Weather report for Tuesday, August 27 — the day I crossed the Presidential Range.

"Spent night before last at Lake of the Clouds [a hut near the summit of Mt. Washington], and had planned to come here [Mizpah Hut, another hut near treeline on the Presidential Range], but the hutmaster said no one was to leave the hut except to go off the mountain due to 25 degree temperatures, high winds, clouds, and snow..."

A hiker's notes in the Mizpah Hut log book, August 29, 1965

As you can see from the above, I caught a huge break in the first leg of my Appalachian Trail hike — one I had been hoping for since I planned the trip. That six-day leg, from New Hampshire's Pinkham Notch to Franconia Notch, took me over the roughest terrain of my hike from the point of both weather and trail difficulty.

Mt. Washington, at 6288 feet the highest peak in the Presidential range in New Hampshire's White Mountains, has some of the worst weather in the U.S. The highest wind velocity recorded anywhere on Earth — some 231 miles per hour — was logged there. While summer weather is relatively less ferocious, it can still be pretty severe, as the hiker quoted above found out.

I had planned to do 52 miles of the Appalachian Trail in the White Mountains before starting my hike from the northernmost point of the trail in Maine so that I wouldn't have to cross the Whites in October when winter has already begun above treeline. Even so, I was worried about the weather. A cloud blowing over the mountain can make life miserable above treeline, and a full-fledged storm can kill.

As it turned out, I got just about the best weather I could have hoped for. From above treeline I could easily make out the familiar peaks of Vermont's Green Mountains some 75 miles away, and I had no need for the gloves and the heavy Gore-Tex mountain jacket I had carried with me.

There was no escaping the difficult trails. The first day I climbed 3000 vertical feet in about three miles. Roughly half of this stretch of trail was above treeline, and consisted of nothing but jumbled boulders going straight up the mountain — no graded path, no switchbacks, just awkward stepping from rock to rock. Other days brought 50-foot ledges, sloped nearly 45 degrees, with just the natural cracks in the granite for handhold/footholds. Most routinely involved hopping rocks and dodging roots. Not the type of trails you make two miles an hour on.

In any case, I got through it all in good shape and right on schedule, with only a bit of rain to mar the experience. My point-and-shoot took a beating when I tripped over a root near the end of the last day, but otherwise my gear and my body are holding up well (as far as the latter goes, take a bow, Mr. Aleve).

|

| My first moose of the trip |

Two other items: first, I saw my first moose of the trip. Just after I finished the third day, I was by the main road waiting for Pam to pick me up (I went off the trail that night) when a moose ambled out of the woods about 100 yards away, crossed the road, and grazed his way toward me, totally oblivious to the SUVs and RVs screeching to a stop with their goggle-eyed passengers hanging out ("Honey, I don't believe I'm seeing a moose...."). After a couple of minutes, he wandered across the road and back into the woods, leaving several discouraged tourists in his wake. (There are actually spots along the roads in the White Mountains where groups of tourists routinely park to watch for moose.)

Second, I now have a trail name. All long-distance Appalachian Trail hikers are given a name by their peers which reflects some aspect of their personality, their appearance, their hiking style, or something else to do with their hike. When introducing yourself to another thru-hiker on the trail, you use your trail name instead of your given name. Anyway, I am now Snowbird. (For those of you not familiar with the term, it is applied in this part of the country to those who head south for warmer climates in the fall. That's not a bad description of my hike.)

Pam and I are now in Maine, and I'll be climbing Mt. Katahdin, the northern terminus of the trail, on Wednesday this week, weather permitting, and heading south after that. The first 100-mile stretch has no significant road crossings and is traditionally known as the Hundred-Mile Wilderness. I should be able to send another note after that.

Rick

Rick's Appalachian Trail hike email #2

September 13, 2002

Farmington, Maine

So far, so good. I've climbed Mt. Katahdin and made my way through Maine's Hundred Mile Wilderness, emerging today with tired and smelly feet, the longest beard of my life, and with another 114 miles noted in the log book.

Unfortunately I didn't catch the same break for Katahdin that I did for Mt. Washington. On Wednesday Sept. 4, the day I climbed the mountain, park officials did not recommend any hikes above above treeline, although no trails were closed. The weather was totally socked in, with clouds, light rain, and maybe 100 feet of visibility. I climbed the mountain with a retired Army officer who had hiked all the way from Georgia. After the first two easy miles, he left me in the dust when the mountain got steep (very steep) in the third mile. Lots of hand-over-hand climbing and several spots with iron bars set into the rock to make reaching the next higher ledge possible. Fortunately, there was little wind and the temperature remained in the 50s, so making it to the top was just a matter of hanging in there.

After the weather cleared, I got my first real look at the mountain the next day from 15 miles south at the gateway to Maine's Hundred Mile Wilderness. Although not true wilderness (I crossed several logging roads and one railroad track over the next eight days), it is said to be the most isolated stretch on the Appalachian Trail.

The trail winds past remote lakes, through spruce and hardwood forests, and like the White Mountains to the south, the trails are all rocks and roots. The weather was good for the most part, except for one day when a cold front passed over about noon, leaving me high on a ridge with a four-mile walk full of steep ups and downs over slippery rocks with driving rain and high wind to the shelter where I had planned to spend the night. I enjoyed the hiker camaraderie that develops when several people are hiking in the same direction at roughly the same pace and keep meeting up along the way. In addition I saw another moose — this one with a full rack of antlers — and was very surprised during a rest break at a brook to see a mink bound by, jumping from rock to rock.

For those of you who have read Bill Bryson's description of his trip on the AT, you may recall his shock when he followed the trail into Maine and first realized that he was going to have to ford some streams — that's right, they don't build bridges for large stream crossings on the Appalachian Trail in Maine, just for small ones, and then only occasionally. I've caught a break of sorts, though — the drought has been so bad in Maine that streams described as "typically knee-deep" in the guidebook have been crossable with judicious rock-jumping. Not a break for the drought-striken Mainiacs, but it's made my life a bit easier.

The Hundred Mile Wilderness was the longest stretch without a break in the trip. The next couple of stretches will be three and five days each. I'll try to send another note in a week or so.

Snowbird

Rick's Appalachian Trail hike email #3

September 21, 2002

Farmington, Maine

Another 75 miles on the log book in the past week, putting me up to nearly 250 for the hike so far. This last week's hiking was a relatively unexciting stretch: almost flat on a relief map — a few peaks here and there, but nothing too exciting. Yesterday, however, the experience changed to what is going to be representative of the rest of Maine — instead of a flat line on the relief map, picture a string of Ms. That is to say, serious ups and downs. The rest of Maine is a series of 4000-footers. These are not bumps on a single ridge, but have significant gaps between them. So, I'm going to be going up and down big-time for the next couple of weeks, and calling on Mr. Aleve to get me through.

One of my readers writes, "You write of the challenges. Tell us how you are feeling — emotional ups and downs etc of being in the wilderness, the exertion, the aloneness." Good question. Let me talk about the experience, and the reactions I'm having.

Because the trail is so rugged, the hike demands almost moment-by-moment focus on where I'm placing my feet. Sad to say, but most of the time I'm more conscious of the trail than I am of the surroundings. Compare walking the trail to running a black diamond ski run — it's not as fast, but it requires the same kind of concentration, especially coming down a steep grade, to deal with it safely. My conditioning over the past year seems to have prepared me well for the effort required.

|

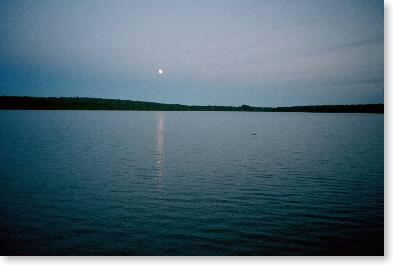

| This I enjoy... |

When I get a chance to step back and relax, I can, and do, revel in the environments — the different types of old familiar New England forests that I'm seeing. I very much enjoy watching the moon rise over a quiet lake, with the reflection of the moonrise in the lake, and later hearing the loons' haunting song. I feel pride when I can look back at a ridge of 4000-foot and near-4000-foot peaks and say, "By God, I did that all since lunchtime." I'm comfortable with the aloneness, because that's my nature and because there are enough encounters along the way to nourish me.

Emotional ups and downs? I'm cautiously up right now because things have gone according to plan. Nothing has come seriously unglued yet — the things that have broken, like my trekking poles, we've been able to replace. Things are on schedule and my body is holding up — which in itself is a source of quiet pride. I just hope I can keep things together now that the going is going to be tougher.

Rick (aka Snowbird)

P.S. to all her friends: Pam is doing fine. Our room in Farmington has suited her well for her quilting, and she is busy cranking projects out. She and I have been able to stay in touch with the satellite phone, and believe me, it is a treat to have someone pick you up after three or four days hiking with a beer in a cooler in the back seat.

Rick's Appalachian Trail hike email #4

October 2, 2002

Farmington, Maine

As of today, when I came off the trail in Maine's Grafton Notch, my mileage total is up to 339 miles even — just the barest hair short of halfway on my planned 678.2-mile walk. I've gone through some of Maine's toughest terrain, and still have Mahoosuc Notch — a mile of crawling over, under, and around boulders — to look forward to. Just as an idea of how brutal the terrain has been, in the course of seven miles between lunch one day and lunch the next day earlier this week, I climbed 2400 vertical feet and descended 3400 vertical feet.

Things continue to go well — my mileage is down to about eight miles a day, but that feels right given the terrain — and my body seems to be holding up. Next week, I'll reach Pinkham Notch in New Hampshire, where I started in August. At that time we'll be relocating to White River Junction, Vermont, and I'll be hiking the trail across western New Hampshire and Vermont.

At one time or another in the course of this hike and my preparation hikes earlier this year, I lost, misplaced, or forgot to pack the following objects: my wallet, my 2-1/2 quart water bottle, my snacks for three days, several bandannas, my multitool (a pocketknife on steroids), my baseball cap, my spoon (the only utensil I normally use), and the stuff sack for my pack cover. I almost lost the only pair of briefs I had with me when another hiker decided they looked like his hanging on the line next to the shelter (they did, actually) and started to take mine instead.

All joking about briefs aside, losing or forgetting things can raise serious problems on a hike like this. The day I forgot to pack my cap, I was doing a ridge walk in the Santa Cruz Mountains in California with bright sun and temperatures above 80 degrees predicted on the ridge. I still don't know where I lost my water bottle, but it was missing when I repacked my pack the morning after I came in from several days on the trail. If I hadn't noticed that it was missing, I would have had to get by with the two other, much smaller, water bottles I also carry — which would have been inconvenient at best. I saw a hiker who forgot to pack a fuel canister for his stove reduced to begging from other hikers.

So what happens? For one thing, you learn to improvise. In the case where I left my baseball cap home on the hot day, I wore my bandanna on my head instead. You also learn patience. My multitool, missing from its usual pocket at noon, turned up at the bottom of my pack that night. You carry a spare of really key things. While Pam worried because my spoon was sitting in the dish rack at the motel, I went to the spares/repair bag in the bottom of my pack and dug out the spare I've learned to carry. And sometimes "trail magic" comes through. The stuff sack for my pack cover was found by one hiker, given to another faster hiker to carry ahead to me, and left in a shelter down the trail, where I found it a couple of days later after having gone off the trail for a break and come back on.

Oh — and if you ever find the bandannas, let me know where they are.

From the trail register at last night's shelter: "We are three middle-age guys, friends/brothers for 43 years, off on our annual weekend trek. Never before have we seen so many Georgia to Maine hikers. Very impressed with their effort. By the way, while you've been in the woods, the economy has gone down the tubes and we appear to be on the brink of war. My advice: avoid reality for as long as possible. Perhaps you should consider walking back to Georgia."

For my California friends, I was fortunate enough to be able to watch the Giants beat the Braves in the first game of the playoffs today, and will be fulfilling my promise to take a radio with me on the trail now that the Giants are in the playoffs. Go Giants (and A's)!

Rick

Rick's Appalachian Trail hike email #5

October 10, 2002

White River Junction, Vermont

The last seven days have brought considerable progress. My mileage total is up to 391.2, and I'm finished with Maine and nearly done with the really hard section of New Hampshire.

Maine's Mahoosuc Notch — billed as the toughest mile on the Appalachian Trail — was worthy of the label. Picture, if you will, two steep mountains with exposed rock faces near the top separated by no more than a couple hundred yards — sometimes much less — for the distance of a mile. Over the years, huge boulders have sloughed off the cliffs and filled up the gap between the two mountains. Most are a few feet across, but some are much larger, and they've landed on top of each other at random angles.

Since you're at a moderately high altitude in the north woods of New England, the forest cover is predominately white birch, red spruce and balsam fir, and these trees have taken root and grown between the boulders as well as along the mountainsides, their roots stretching along the boulder faces. The predominant color is a dark green, but the bright yellow of the autumn birch leaves provides a startling counterpoint. The day is cloudy and cool, and there was a brief shower earlier, but fortunately the rock faces are not slippery.

The usual white blazes mark the path, but there's no trail in the usual sense. You move from boulder to boulder, using not just your feet but reaching and pulling yourself up and over the rocks with your arms. Sometimes you climb over, sometimes you pass through gaps. Sometimes there are huge spaces underneath the boulders, and the blazes direct you to passages underneath the boulders. Sometimes the roots provide a foothold; other times you depend on your shoes to grip the boulders and provide leverage. At least twice the passage is so narrow you have no choice but to take your pack off and push it through ahead of you. In spots, the boulders recede and you seem to be walking the usual rocky trail through the forest, but in a minute the boulders return and you're scrambling again.

I pass through Mahoosuc Notch with three gentlemen from Maine. We had met the day before on the trail and they were quick to invite me to join them. I was interested in going with other people mostly for safety reasons, but there are also places in the notch where one person working with another can get through a spot which would be not be possible for a single hiker.

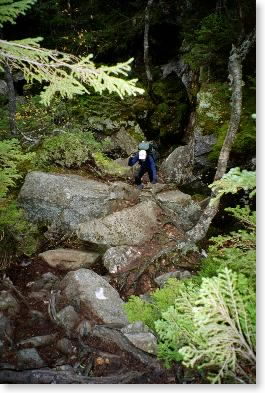

|

| Snowbird having fun in Mahoosuc Notch |

At first, it's fun. You seem like a kid again, scrambling on the jungle gym at school. But after an hour or so, it begins to seem endless, and the false starts you make every now and then seem more and more frustrating.

Finally, after three hours, you reach the trail junction that signifies the end of the notch. Since you got a late start into the notch, and since it took so long, it's after 5:00, and you now have a one-mile hike up and out of the notch, with an altitude gain of nearly 1000 feet, to reach the lean-to where you'll spend the night.

By the way, that day shows as 5.1 miles in my log book.

Go Giants!

Rick

Rick's Appalachian Trail hike email #6

October 19, 2002

White River Junction, Vermont

I crossed the Connecticut River today at Hanover and put 442 miles and the two toughest states on the Appalachian Trail behind me. Maine and New Hampshire are done. I always had as my minimum drop-dead come-hell-or-high-water goal to make it this far, and that goal is met. That's the good news.

Now the bad news — because I fell several days behind plan on this last stretch (due mostly to my own poor planning), I don't have enough time to do the four days I need to do in central Vermont before we have to move on to Massachusetts. That move is primarily driven by a commitment Pam has to fly to a quilting retailers convention. Her plane leaves from Albany (which is near our Massachusetts base) the morning of the 23rd, which means we need to drive down there the afternoon of the 22nd.

So... some of those Vermont miles aren't going to get done. Too bad, but for me Maine and New Hampshire were always the heart of the experience, and those states are in the bag. I should be able to get two days of hiking done in Vermont, but not the four I need.

How would I describe this last stretch? For one thing, the nine days was the longest I went on this trip without the comforts of home (a soft bed, shower, etc). Lots of grey weather — not necessarily rainy, just grey. That took some of the edge off the foliage, which was at or near peak during the week.

I managed to win one of the gambles in my schedule, which was that I would arrive at New Hampshire's Mount Moosilauke, a 4,800-foot peak with a significant above-timberline area, before winter had set in on the summit there. Actually it was kind of a tie; it was rainy and in the 40s the day before I got there, but that night a cold front came through and dropped the temperature into the 20s. I (and many others) awoke that morning to frozen water bottles and boots. Going over the summit, there was ice on the trees and the grass above timberline for the last 500 vertical feet. The temperature at the summit was 20 degrees and the wind was gusting to 40 mph, making the chill factor well below zero. The views were impressive, but nobody wanted to hang around too long.

An interesting aspect of this last stretch of trail is that the maintaining organization changed from the Appalachian Mountain Club to the Dartmouth Outing Club. Hardly exciting, you say, but just wait. The organization that maintains the trail has a impact on the tone of your experience. The signage is different and the approach to hiker education is different. And, while the Maine Appalachian Trail Club and the Appalachian Mountain Club (the two previous maintaining entities) have been generally no-nonsense, serious, very environmentally conscious organizations offering straightforward shelters and perfectly comprehensible one-holer privies, the Dartmouth Outing Club is off the wall.

|

| Does this compute? |

Imagine, if you will, a six-sided shelter with a five-sided privy. Or try to conceive of a shelter that has an oil painting (your basic flower vase still life) on the wall and a privy with a drawbridge door. That's right — you pull the door down (and there are counterweights, just like on any good drawbridge) and the door stays down while you do your duty and contemplate nature. Or a shelter with a freestanding stone fireplace at least fifteen feet high facing it (and no, I could not see any evidence of a fire that burned a predecessor building to the ground) and with a privy with a seat with arms and a backrest, but with no roof. Or a sign on the trail: "No unicycles." Or a privy with a floor plan so strange I can't even begin describe it. It must be either those long winters or an architecture department with a penchant for bizarre assignments — that's all I can guess.

(Out of fairness to the Dartmouth Outing Club, I should mention the two-seater privy in Maine that had a cribbage board between the two seats and a sign over the door which read "Your Move." Subtle folks, those Mainers.)

Snowbird

Rick's Appalachian Trail hike email #7

October 30, 2002

Lee, Massachusetts

I've continued to make progress since Hanover. As I said in my last note, I wasn't going to have time to do all of the Vermont miles, but I did do half of them — about 20 miles in two days — before we had to move to Massachusetts. Since we got to Massachusetts, I've knocked off 65 of the state's 90 trail miles.

Because I've fallen so far behind, I've decided that I'm going to forget the miles I'd planned to do in New York and that the Connecticut/New York state line — the New England border, so to speak — is going to be the end of the trip. That's 50 miles shorter than what I had planned, and with the miles I didn't get done in Vermont and the miles I've done already, that'll mean that my total trail miles will come to just over 600 if I make it that far. As of today, I've done over 546 trail miles, and I have only 57 miles to go. That ought to take less than a week, if the weather doesn't get any worse.

|

| Winter arrives early |

Winter definitely arrived early in New England, and the temperature this past week has been five to ten degrees below normal. There was snow in the mountains of Western Massachusetts a week ago, and I spent several miles in snow when I traversed Mount Greylock, Massachusetts' highest peak, last Friday. In fact, it was cold enough for the snow to still be powder at higher elevations three days after the storm. Most of the walking here and in Vermont has been relatively easy woods walking, with few steep hills, few rocks, and generally smooth trails. What a pleasure after New hampshire and Maine. The hikers are thinning out, for sure. I haven't seen anyone else on the trail the last three days.

Since Hanover I've adopted a much different hiking style — one referred to on the trail as slackpacking — and of the nine days I've been on the trail since I got to Hanover, six have been slackpack days. Instead of normal trail hiking, where you carry your food, bedding, and shelter with you, and orient yourself to reaching a shelter or campsite along the trail, when you slackpack you go from one road crossing to another in a day, carrying only a day pack and relying on off-trail sources for your breakfast, dinner, and lodging.

I've had some good reasons to get into slackpacking in the last two weeks. First, it's worked out logistically in Vermont and Massachusetts, as our lodgings have been close to the trail. Second, I realized that I was losing considerable weight and wanted to beef myself up with good restaurant food as much as possible. Third, as a loyal Giants fan, I had to give myself a chance to watch the Series on television.

Although the Appalachian Trail traverses a great deal of wilderness, there are enough road crossings so that it is relatively easy to slackpack most of the trail, given proper support. Many lodging vendors who are oriented to hikers offer slackpacking support as a way of boosting their revenue. Stay with me, they say, and I'll bring you back to the trail in the morning, pick you up at the road crossing 15 miles to the south — and of course sell you a second night of lodging. Some vendors have even sold a group slackpack Appalachian Trail thru-hike, with vans following the hikers for more than 2,000 miles and taking them off the trail each night.

The question is, does this cheapen the traditional backpacking experience? Do thru-hikers who take advantage of slackpacking diminish their accomplishment? One answer comes from the Appalachian Trail Conference, which governs the trail. They make available an award called the "2,000 Miler" to anyone who has hiked the entire trail. The only question they ask is, "Have you walked past all the blazes?" Whether or not you hike the entire trail at one time, how long you take, how much weight you carry in your pack, whether or not you spend the night on the trail — none of that matters to them.

Some continue to think that slackpacking diminishes the experience. I only know two things: one, most long-distance hikers slackpack, given the opportunity, and two, all this proves is that hikers are just as capable of splitting hairs as any other group. But I should say that I'm proud that I didn't slackpack at all in Maine and New Hampshire, which was the core of my hike.

Snowbird

Rick's Appalachian Trail hike email #8

November 5, 2002

Litchfield, Connecticut

Well, folks, it's a wrap. Sometime this morning while walking along the Housatonic River, I hiked my 600th mile of this fall's trip on the Appalachian Trail, and later reached the Connecticut/New York state line to finish the 141 miles of the Massachusetts and Connecticut sections of the trail. Today's 4.1 miles bring me to a total of 603.3 miles for the trip. With that, I'm calling it quits.

This past week was very similar to the previous week. The weather continued unseasonably cold — it was down to 20 degrees last Saturday morning, and there was an inch of snow outside my shelter Sunday morning in the hills of northwestern Connecticut. The transition into Massachusetts and Connecticut brought more fall colors, with the oak color of southern New England added to the maple leaves still lingering on the trees. I was pleasantly surprised by the Taconic range in northwestern Connecticut — lots of very nice views and more than a hint of the ruggedness of New Hampshire and Maine to the north.

Here's how the miles I initially wanted to walk reconcile with what I actually completed:

785.6 AT miles, Mt. Katahdin, Maine, to Hudson River, New York

- 106.0 New England AT miles I'd walked in the past

679.6 AT miles I set out to walk, fall 2002

- 52.8 New York AT miles I finally decided to skip

- 23.5 Vermont AT miles I wasn't able to walk

603.3 AT miles walked, fall 2002

Another way of looking at it is to focus on New England, which is pretty much what I decided to do near the end of the trip. I've now walked 709 of the 732 AT miles in New England, with just those 23 miles in Vermont left to do someday.

In addition to the 603.3 trail miles, I also walked 17.3 miles that were either official blazed side trails, to and from shelters or viewpoints, or AT miles necessarily duplicated in the course of the hike. So, if you add it up, I walked over 620 trail miles in the course of the hike.

Pam and I are leaving for home Thursday morning, and on the way I hope to have a little more time to reflect on the trip and to also put some numbers together. I hope to be able to get out a final hike email after we get home. If any of you have any questions that you want me to answer in the final email, send them along.

I couldn't have done this hike without the assistance of a lot of people, and I owe many of you thanks for your suggestions, support, and other assistance. I hope to send out or personally convey individual thank-yous after we get home.

Snowbird

Rick's Appalachian Trail hike email #9

November 14, 2002

San Mateo, California

How to wrap up the hike? On our cross-country drive home, I had a chance to build a spreadsheet and came up with some numbers which describe the experience pretty well.

First, I was on the trail on 67 calendar days between August 19 and November 5. On many of these days I spent less than a full day on the trail, so I devised a unit of measure called a trail day, which represents the fraction of a day I spent on the trail.

My entire trip totaled 60-1/2 trail days. Since I covered 603 miles on the AT in those 60-1/2 days, I averaged almost exactly 10 miles per trail day. My shortest full day on the trail was slightly more than five miles (going through Mahoosuc Notch in Maine); my longest was 15, on the last day before a rest break near the start of my walk south in Maine.

During the most difficult stretch of the trail — the 200 miles from Stratton in western Maine through the White Mountains of New Hampshire which made up the middle third of my hike — my average miles per trail day dropped to 8-1/2, and in Connecticut and in the early part of the Maine hike, my average was upwards of 12 miles per trail day. If I add in the side miles I hiked (mostly to and from viewpoints and shelters), these averages all move up a bit, but not hugely.

The other interesting stat is the breakdown of where I stayed each night. Of the 67 calendar days I was on the trail, I slackpacked (or day-hiked) 11, and by definition, I was off the trail those nights. Of the remaining 56, I was in shelters for 29 nights (ten nights by myself), in my tent for nine nights (all in Maine, where there are fewer restrictions on camping and where "stealth camping", or tenting away from developed campsites, seems to be more common), in a hut where meals and beds were provided for five nights, and off the trail 13 nights. I hadn't foreseen that I would be slackpacking so much, but otherwise this mix is about what I had expected. The off-trail numbers are probably a little higher than for most long-distance hikers, but not outrageously so. Most distance hikers took town breaks at least once a week, and those had a tendency to stretch out into a second day.

Since the hike is over, I promised in my last letter that I'd take questions. Not many came in, but I came up with a few myself to pad the list.

Q: Are there any insights you'd like to share after ten weeks in the woods?

A: Yes: no one sponsors a tree. I was getting thoroughly sick of the degree to which commercials intrude on our lives, especially the baseball game commercials which hook an event of the game to a pitch for their product (as in when a relief pitcher is summoned in a ball game, "When it's time for a change, think Spee-Dee oil change").

It was totally refreshing to be in an environment that was free of commercial presence or interruption. This is not to say that the trail was message-free (there were signs in the shelters and on the trail urging hikers to carry out their trash) but at least these messages weren't in-your-face product pitches.

Q: Despite your apparent distaste with commercials, are there any products you used which you would enthusiastically endorse?

A: Most everything I took with me served its function well, but there were two products without which I could not have finished the hike. First were my Leki trekking poles. Trekking poles are superfluous on flat, easy surfaces with a minimal load, but on the rough trails of Northern New England and with the load I was carrying, they saved me from numerous falls, helped me use my upper body strength to assist on climbs, and helped preserve my knees on the downhills by allowing me to plant my poles below my feet and lower my body weight down.

Second was Endurox, a performance recovery drink I carried with me in powder form and drank every day at the end of the day's walk. When I neglected to do this two days in a row on easy terrain and woke up stiff and sore the next morning, I realized just what a difference the drink was making. As long as I had my drink at the end of the day, I never woke up sore the next day and never felt like I couldn't get started and do the day's hike.

Q: Did you ever get lost?

A: Yes, once, on one of my Vermont days. The trail followed an old woods road up one side of a ridge and down the other side to a road. On the way down, in an open area in the woods, I lost the footbed of the trail in all the leaves that had fallen and missed the spot where the trail went off the woods road and into the trees and down to the road. I ended up finding my way down to the road and making a guess (which turned out correct) as to which way I had to turn to pick up the trail. I found the trail where it crossed the road a couple hundred yards away.

Q: What was the best part of the hike for you?

A: There were no huge moments of ecstasy. Just walking in the New England woods in the fall, day after day, was enough for me. Even though the foliage wasn't the greatest ever and there was a lot of gray, cold weather in October and November, the hike definitely lived up to my expectations.

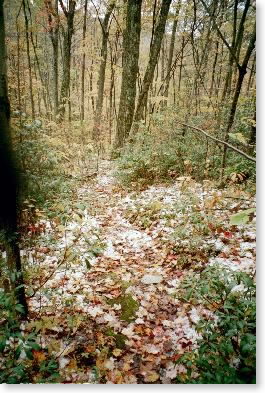

|

| This is what the trail looked like.... |

Q: What was your worst day?

A: The day I went over Sugarloaf Mountain, one of Maine's highest peaks. I had tweaked my knee the day before and it started to bother me again as I went up the mountain. Then I was ambushed by hornets and got three very painful stings. I made it over the top of the mountain and down the other side slowly, taking it very easy with my knee. Then the topper: on the map it looked like two level miles from the bottom of the mountain to the shelter I was planning to stay in, and I was hoping they'd be easy. They turned out to be the worst type of Maine trail, all rocks and roots, and it was just an awful walk to the shelter.

Q: What happened then?

A: Fortunately I had a three-mile walk the next morning out to a road crossing where I was meeting Pam for a rest day. That stretch of trail wasn't bad and my knee seemed much better after a night's rest.

Q: Did you experience moments of loneliness or fear?

A: No to the first. Fear is not quite the right word, but there were a couple of times on the hike when I was very concerned about the consequences if something negative happened, like if I missed a sign to a shelter on a cold rainy afternoon.

Q: What did you read?

A: During the first couple of weeks, nothing. Then I packed Walden, and found that Thoreau got dull in a hurry. I quickly ended up carrying the usual trash paperbacks.

Q: What did other hikers find most remarkable about your hike?

A: The fact that my spouse was following me along, living in a motel, supporting me with supplies and running me to and from the motel on rest days. Most long-distance hikers struggle a bit with the issue of food resupply, and having this all organized off trail was another huge benefit. One Mainiac my age said pigs would fly before his wife would support his hiking, but it wasn't just the more experienced hikers, the younger hikers appreciated what a great deal I had too. And believe me, if you ask Pam, she'll tell you that she got lots of quilting done and had a good time overall (except for one hotel which shall remain nameless).

Q: What were the strangest things you saw other hikers carrying?

A: I actually met a guy — who claimed to be a thru-hiker — who was carrying, among other things, a small portable TV, a medium-format camera, and a digital video editor. He had started in Georgia, hiked part of the way north, jumped to Maine, and was working his way south slowly. He claimed to be working on a coffee-table book about AT thru-hikers, and was shooting photos of all the thru-hikers he met.

Q: Now that you've pretty much done the Appalachian Trail in New England, do you feel like doing the rest of the trail?

A: Not particularly. New England was where it was at for me. I definitely want to finish the 23 miles in Vermont that I missed, but I think I'll look elsewhere for my next hiking adventure. [After-note: I'm now planning on doing the Tahoe Rim Trail, which circles Lake Tahoe, this coming September. It's about 168 miles, and looks like relatively easy going after the AT in Maine and New Hampshire.]

Q: Any physical consequences? Are you exhausted?

A: Well, I lost at about fifteen pounds -- some of which I've gained back. My knees are sore — which I blame on a couple of days when I pushed pretty hard near the end of the hike — and I'm glad to be giving them a rest. I have a sore shoulder, due to a fall I took a couple of days from the end. But no, I'm not exhausted. And my beard is doing very well, thank you. If you have HTML email, click on this link to see me with my beard:

That's all I've got. Thanks for coming along with me. I've enjoyed putting these emails together and I very much appreciate your enthusiastic response to them.

Snowbird