Mini-Dict of premodern texts, people, places and terms

Texts, People, Places, Terms (premodern Japan)

A (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

aware: see mono no aware

B (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

bakemono: see spirits

banka (“laments” 挽歌)

A category of poetry. One of the categories within the Man’yōshū that is considered especially good.

"banquet mode"

A term I am using to highlight an important aspect of premodern Japanese poem composition, namely, that they were frequently recited in public spaces, in situations where composer and listener could be considered to be able to switch places, and under implicit understandings regarding good taste and more specific, community-wide aesthetic values. I’ve set “banquet” poetry in contrast to one notion in the West of a poet, alone with his or her muse, writing unique expressions that are meant to present the world in both a radically different way and a “true” way. “Banquet” poetry is less committed to either of these positions. I’ve developed my own way of thinking about “banquet” poetry but it still resembles considerably its source: Ōoka Makoto in his The colors of poetry.

Bashō: see Matsuo Bashō

biwa hōshi ("lute priest" 琵琶法師)

"Itinerant performers, usually blind, who chanted works of vocal literature to the accompaniment of a biwa (lute). Biwa hōshi shaved their heads and dressed as traveling priests but were not formally ordained." (Encyclopedia of Japan, Kodansha) It was the biwa hōshi who chanted / performed The Tale of Heike and the widely used written version today of The Tale of Heike was originally the performance of a famous biwa hōshi performer named Akashi Kakuichi.

Buddhist reforms of the Kamakura period

The Buddhist reforms don't happen on a specific date in time. "During the 12th-13th century" is about as specific as is necessary for this class.

The basic points are that a reconnection with the continent (China) includes the travel to that country by Japanese Buddhist monks to learn more about Buddhism. They bring back ideas, found sects, and so on. All of these sects revitalize Buddhism in some way, spreading its influence. From our cultural perspective, I treat this period of reform as something of a watershed event, with literature and other cultural expressions mostly different depending on which side of this divide they were made. (This is NOT true of everything of course.) The Buddhist assertions that life is suffering and that all is impermanent, among other things make a strong mark on the arts. These reforms happen at different times and places, within different sects and led by different individuals. See the PDF on this for specifics (not required for testing purposes). In general, sects are, on the one hand, "grace-oriented" sects where the believe is that individuals are not strong enough to find enlightenment on their own and should call, with faith, on the buddhas and bodhisattvas for help and, on the other, "self-powered" meditative, monastic efforts where it is believed that the only way to enlightenment is through insight that happens as a result of one's own efforts. These are called, respectively "ta-riki" (他力, other-power, lay life—having a family—possible for some of these sects, grace of bodhisattvas and buddhas) and "ji-riki" (自力, self power, monastic life, study & meditation).

Here are the main reformers and the sects they established. There is a PDF on bSpace (probably titled Kamakura Buddhist reformers) with further details:

Tariki (grace) sects

- Hōnen 法然 (1133-1212), founded Pure Land sect / Jōdo shū 浄土宗

- Shinran 親鸞 (1173–1263), founded True Pure Land sect / Jōdo Shinshū 浄土真宗

- Nichiren 日蓮 (1222-1282), founded Nichiren Shōshū 日蓮正宗

Jiriki (meditation) sects

- Myōan Eisai 明菴栄西 (1141-1215), founded Rinzai Zen / Rinzai shū 臨済宗

- Dōgen 道元 (1200-1253), founded Sōtō Zen / Sōtō shū 曹洞宗

bunraku: see puppet theater

bushidō ("Way of the warrior" 武士道)

Bushidō is one of those terms that has been entangled in the West in popular language (since it is a common element in video games), stereotyped characterization of Japan (usually with negative connotations—the "economic animal" portrayal of the Japanese in the 1980s for example was based in part on the idea of a warrior cult among Japanese businessmen), and, in the world's perception of Japan post-World War II. It is not easy to find academically solid, unprejudiced discussions about this topic online, amongst all the chatter, so proceed with care.

The concept of "michi" ("dō" 道) is a medieval one, linked in part to Zen Buddhism (but this link is usually over-emphasized in exoticized descriptions of "the Way" in the West), that asserts that there is a spiritual benefit to fully mastering an art under the direction of a true master of the art. Kendō ("way of the sword" 剣道), chadō ("way of tea" 茶道), kadō ("way of flower arrangement" 華道), kōdō ("way of incense" 香道) are some other examples. Practitioners in all of these arts are expected to display concentrated effort to learn precise practice techniques, learn and accept an orthodox history of the art, and pledge allegiance to the group or organization promoting (and policing the standards) of the art. The intensity of bushido derives not just from the content of the practice itself (the ferocity of the fighting warrior, the absolute nature of his loyalty), but from a spiritual, Zen, context where devoted, selfless practice of a universal form is an aid towards spiritual awakening.

One of the problems, then, is confusing the specific bushidō systematic philosophy / ethical code with a more general, loose set of values having to do with common attitudes, practices and such within warrior clans. Bushidō ≠ a great and secret and age-old warrior tradition. It is a recent formulation of Confucian values designed for the elite and leading class of Japan, including the interpretation and exercise of ethical values. This elite had been the court aristocracy but through the many wars of the country, the samurai class (because it was from this class that leaders arose) began to make a serious claim on being the standard for behavior, although they never rejected courtly values altogether.

It is this background, and the tendency to glorify war and its warriors, that is part of the soaring idealism of the concept. At heart, it seems to me, there isn't a magic or secret formula to this practice. The code simply asserts most of the Neo-Confucian values (loyalty 忠, righteousness 義, sincerity 誠・信, benevolence 仁, propriety 礼) that are expected of us all, with these important adjustments: principle is put before one's own well-being so death becomes an acceptable outcome of the code, loyalty becomes dominant, shame (dishonor, that is, the failing to uphold the code) is highly energized, and the ultimate direction of the teaching is towards determining effective, decisive action—in nearly all cases envisioned as being carried out by male subjects.

Despite popular teaching, bushidō is not a centuries old tradition; it is relatively new in the making, pretty much after all the internal wars settled and the Edo period was in place. (See Karl Friday: The Historical Foundations of Bushido. The best articulation of the code is a turn-of-the-20th-century work by Nitobe Inazō (新渡戸稲造): Bushido, Soul of Japan: An Exposition of Japanese Thought) There were warrior clans to be sure, and warriors must have a code of conduct to be strategically and tactically effective, but that does not therefore mean that they were ancient practitioners of a "way". They were just disciplined fighters, strong on clan (or other) loyalty.

For J7A students, there should be a handout on bSpace titled something like Bushido diagram.

Buson: see Yosa Buson

C (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

cha no yu ("tea ceremony" 茶の湯)

From Kodansha's Encyclopedia of Japan: "A highly structured method of preparing powdered green tea in the company of guests. The tea ceremony incorporates the preparation and service of food as well as the study and utilization of architecture, gardening, ceramics, calligraphy, history, and religion. It is the culmination of a union of artistic creativity, sensitivity to nature, religious thought, and social interchange."

Cha no yu (茶の湯, "hot water for tea") is considered now to have been founded by Sen Rikyū. It has its roots in Eastern Hills culture. Similar to No drama, the innovations introduced by Rikyū had an impact on a large number of arts, in particular: garden design, ceramics, architecture, and flower arrangement. Rikyū developed the aesthetic/ethical concept of wabi to a high degree and it is associated today with the tea ceremony.

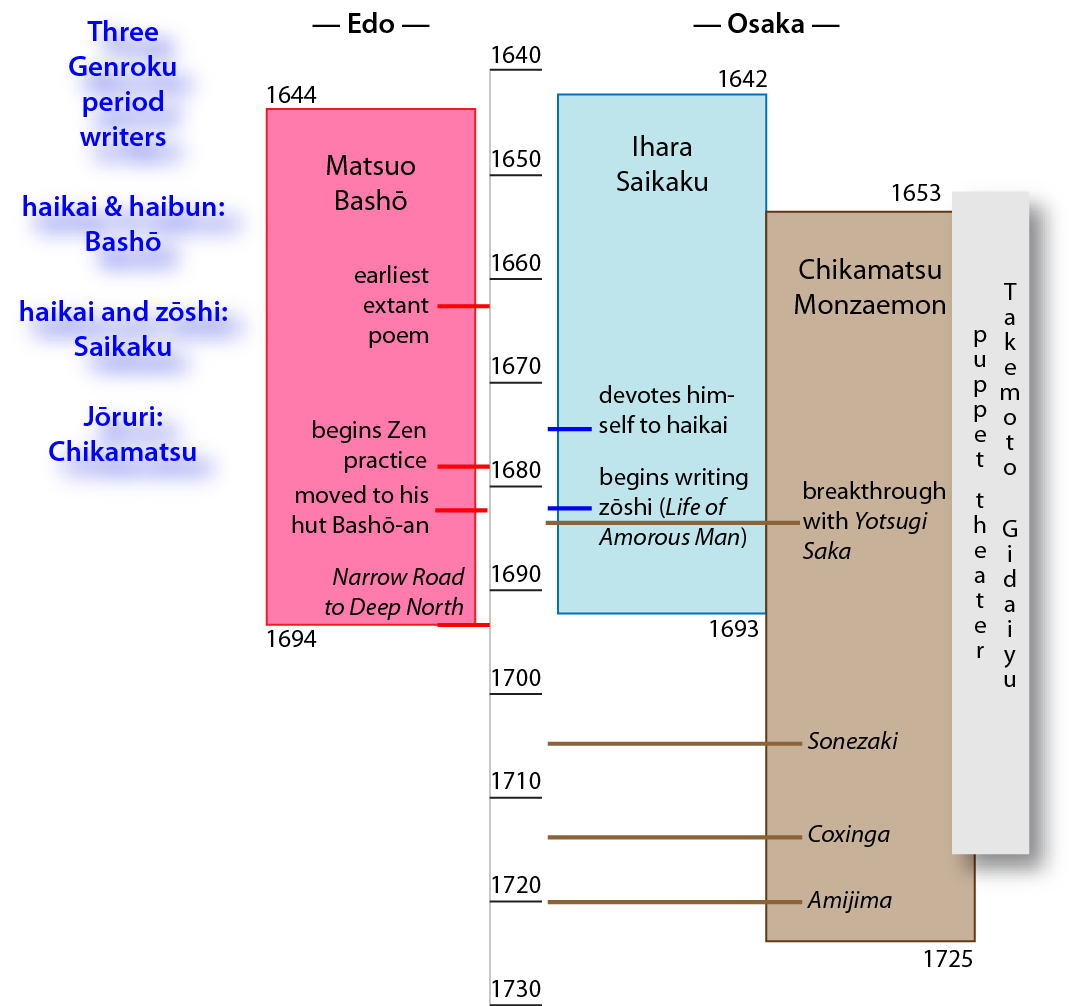

Chikamatsu Monzaemon (近松門左衛門, 1653-1725)

A Genroku period playwright, one of the greatest of premodern Japan. He wrote more than 100 plays, for both the puppet theater (bunraku) and kabuki.

His father was a rōnin (lordless samurai). Active in Osaka.

Chikamatsu is one of the three great writers we consider during the Genroku era (the other two are Ihara Saikaku and Matsuo Basho). He wrote historical plays and household plays. A common theme is the exploration of shame (haji 恥) related to complications of conflicting giri (duty 義理) and situations resulting from strong ninjō (人情, human affection here best thought of a passionate love). His famous Loves Suicides at Sonezaki (Sonezaki shinjū, 曾根崎心中, 1703) and Love Suicides at Amijima (Shinjū Ten no Amijima, 心中天の網島, 1720) concern a weak merchant and his more morally strong mistress and wife. Sonezaki was so popular that there was a increase in real love suicides and a law had to be passed banning them. The Battles of Coxinga (Kokusen'ya kassen 国性爺合戦, 1715) is probably his most famous and successful play. Masahiro Shinoda's film "Double Suicide" (Shinjū: Ten no Amijima, 1969)" is an interesting exploration of the themes of the play.

I really like his "Skin and flesh" theory of aesthetics. I think this has helped me better understand and be more deeply moved by "theater" or any art form (including types of prose) where "artifice" is on prominent display:

"Art is something that lies between the skin and the flesh, the make-believe and the real. ... Art is something which lies in the slender margin between the real and the unreal. [….] It is unreal, and yet it is not unreal; it is real, and yet it is not real. Entertainment lies between the two."

—"Chikamatsu on the Art of the Puppet Stage," Anthology of Japanese Literature, from the Earliest Era to the Mid-Nineteenth Century, ed. and trans. Donald Keene (New York: Grove Pr., 1955) 389.

As a human figure, the insubstantial puppet is simply unreal. When not actually performing on stage, it hangs on a nail, reduced to a pathetic and insignificant object. However, as soon as the puppeteer sets this pathetic figure in motion, it becomes a human figure that appears more real than real human beings. The otherwise empty outer layer of skin (himaku [skin membrane]) appears to envelop real flesh (niku). The puppet begins to possess both skin and flesh (hiniku [skin and flesh]). Chikamatsu competed with Kabuki because he always wanted the performance of puppets, which consist only of hammock [skin membrane], to surpass the performance of kabuki actors, who have hiniku [skin and flesh]. Behind Chikamatsu's way of reading the kanji for "skin membrane" as hiniku [skin and flesh] rather than himaku [skin membrane], we can see his decisive and enthusiastic attitude as a playwright of the puppet theater.

—"The Hermeneutic Approach to Japanese Modernity: 'Art-Way,' 'Iki' and 'Cut-Continuance' Ryosuke Ohasi, in Japanese hermeneutics: current debates on aesthetics and interpretation, ed. Michael F. Marra (U of Hawi'i P, 2002) 29.

Chiteiki ("Record of the Pond Pavilion" 池亭記, 982)

- Name: Translated as “Record of the Pond Pavilion” which is a literal translation of the title.

- Date of composition: 982 (Heian Two)

- Author: Yoshishige no Yasutane 慶滋保胤

- Genre: this is a little tricky—recluse literature, zuihitsu, or (Chinese) nikki depending of how you are talking about it

- Script [script] used: Chinese

Chiteiki is not a major text for us but it is an important predecessor to the Hōjōki, which we read. The Chiteiki was anthologized in the Honchō monzui (本朝文粋)

chōka (poem form, “long poem” 長歌)

A poem form with this syllabic cadence and number of "lines": 5-7(n), 5-7-7. The poem may have any number of lines in a 5-7 cadence; this cadence will repeat itself; the final lines will conclude the poem with an extra 7-syllable line.

Among the major poem anthologies, the chōka is primarily associated with the first of the major collections, the Man’yōshū (mid-8th c., Nara period).

It never dominated the poetic scene but some of Hitomaro’s most impressive poems are in this form, as is the interesting invective that Michitsuna’s Mother leaves for her husband (and his reply) in Kagerō Diary (ca. 974).

Confessions of Lady Nijō. See Towazugatari.

D (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

diaries : see nikki

dohyō (土俵)

Name: 土俵

"Dohyo - the sumo ring of wrapped straw imbedded in the floor, about 4.6 metres (15 feet) in diameter, on a specially constructed square platform of clay 61 cm (2 feet) high off the stadium floor, with the platform about 5.5 metres (18 feet) on each side." (http://www.tangoll.com.hk/Sumodohyo.html)

The wiki on the dohyō is fine: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dohyō

double suicide: see shinjū

E (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

Eastern Hills Culture (loosely from around 1440 to around 1490)

Name: Higashiyama bunka 東山文化, based on the geographical location: the hills (north-)east of Kyoto where Yoshimasa built his estate.

We treat this as an important cultural moment where develops, under the strong influence of Buddhism and the poetics of linked0verse (renga), cha no yu (tea ceremony) and its key aesthetic wabi.

From Web site Japanese Architecture and Art New Uses System (JAANUS): Kitayama bunka: "Lit. east mountain culture. The culture of the middle Muromachi period *Muromachi jidai 室町時代, specifically that of the eighth shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa 足利義政(1436-90), from the beginning of his rule until his death (1443-90). It is named after the area east of Kyoto where in 1483 Yoshimasa built the "Silver Pavilion" Ginkakuji 銀閣寺 (later called Jishouji 慈照寺) for his retirement. The interiors of buildings were innovative, displaying many features such as *chigaidana 違い棚 (staggered display shelves) and tsukeshoin 付書院 (a shallow desk) that would be incorporated into the *shoin 書院 style of architecture in the succeeding Momoyama period *Momoyama jidai 桃山時代. A great many arts are associated with Higashiyama bunka, particularly the advancement of ink painting *suibokuga 水墨画 under the master Sesshuu Touyou 雪舟等楊 (1420-1506) and the founding of the Kanou school of painting *Kanouha 狩野派. This family of painters under the leadership of Kanou Masanobu 狩野正信 (1434 - 1530) were descended from a low ranking samurai 侍 family from the area around modern Shizuoka preferture. Masanobu was appointed official shogunal painter in 1481. Toward the end of the 15c under Murata Jukou 村田珠光 (1423 - 1502), the act of tea drinking was formalised into a ritual *chanoyu 茶湯. Tea rooms such as the Doujinsai 同仁斎 in the *Tougudou 東求堂 at Yoshimasa's Ginkakuji villa were designed to express the aesthetic concepts of individual tea masters. Thick greeen tea was served, and the objects used in the ceremony were carefully chosen to suggest age and understated elegance. "

emakimono ("scrolls with illustrations" 絵巻物)

"Long, horizontal handscroll, unrolled from right to left, containing illustrations that tell a story, often with accompanying text. The format, recognized as one of the high points of painting in the native Japanese style (see yamato-e), flourished during the Heian period (794-1185) and Kamakura period (1185-1333)." (Encyclopedia of Japan, Kodansha)

Many of the canonical works of premodern Japan, and especially The Tale of Genji were not read by readers in their original, full, text versions but rather through the vignettes provided by emaki.

en (a type of beauty)

Name: 艶, gorgeous beauty, sensual beauty, voluptuous beauty

I have wanted to list this term because it is part of a stream of aesthetics that have to do with sensual, rich beauty: rich colors, somewhat-fleshy feminine beauty, sensuality that comes from abundance. It is not extreme, or anything close to excessive, but it is not ethereal either. We encounter mostly as a component of yōen (妖艶).

en (bonds, relationships)

Name: 縁. This is not the same as the aesthetic value "en" (艶)

I discuss connectedness in various ways in J7A. "En" means a relationship and, frequently, a karmic relationship. In the Heian period prose work Tale of Genji, Hikaru Genji often states that he and a woman have a karmic relationship that transcends this one life cycle. This is a statement of intimacy, and, to some extent obligation and, sometimes, as a measure of the more-than-usual power of the feelings of attraction. In Muromachi period Nō drama, the Buddhist component is emphasized.

Musubu (verb) musubi (noun) (結ぶ・結び): This is one way of discussing or representing the actual-ness or firmness of a bond. Individuals are "tied" to one another. Vines that grow and entwine are used in poetry to express feelings of longing and connectedness. Twisted ropes (nawa) are used in Shintō imagery to show connection (even when they are used as demarcation for a sacred space the sense of the boundary is that one can be connected to this space, not that it is prohibited space). The act of binding suggests promises, including promises of romantic commitment. Elaborate, decorative knots have a long history in Japan and are still very common on gifts.

Essays in Idleness: see Tsurezuregusa

F (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

Fujiwara no Teika, also Fujiwara Teika / Fujiwara Sadaie (藤原定家, 1162-1241)

One of the most important individuals associated with the Shin-Kokinshū (ca. 1205) and one of the most important individuals in the history of premodern Japanese literature. His contributions are in his excellent poetry, his poetics (as practice through his poetry and stated in several seminal essays by him: Eiga taigai, Kindai shūka, Maigetsushō), his scholarship in collecting, accurately copying and sometimes annotating the major classical works of his time (called "Teikabon 定家本"), and his editorial work for poem anthologies, most especially the Shin-Kokinshū.

Son of the eminent poet, scholar and critic Fujiwara no Shunzei / Fujiwara no Toshinari (藤原俊成, d. 1204)

Author of the collection of poetry familiar with most Japanese: Hyakunin Isshu (One poem by One Hundred Poets) that is the basis of the interesting card game done especially at New Year's time. Search videos for: hyakunin isshu karuta or かるた大会 or 百人一首かるた。

Teika's poetics include an early emphasis on yōen and a later emphasis on ushin. In terms of thematic content, his poems often have a sensual, romantic quality and sometimes have a a slight "transcendent" or "other-worldly" component. His virtuosity in poetry is widely recognized, both then and now.

Fūshi kaden (風姿花伝)

A Nō drama treatise, ca. 1402 (Muromachi, Northern Hills Period). For a very good overview see pages 109-112 of The Japanese theatre: from shamanistic ritual to contemporary pluralism by Benito Ortolani (this segment probably accessible via GoogleBooks, use "Fushi-kaden" as the search term). Portions of this document are provided as a PDF (see bSpace). A full translation is in On the Art of the Nō Drama: Major Treatises of Zeami by J. Thomas Rimer and Yamazaki Masakazu (Princeton UP, 1984).

G (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

ga-zoku ("elegant-vulgar" 雅俗)

Ga-zoku is a rubric sometimes used in discussing premodern culture that literally means "the elegant / the vulgar" and basically means "high arts developed, promoted and patronized by aristocrats / folk arts, artisan activities, local beliefs & practices". Often this rubric is used to explore the thesis that most of the high arts first find their origin in folk arts. This template must be used with care, however, since some high arts in Japan are the result of direct import from mainland Asia. Nevertheless, it is good to remember that many of the high art cultural activities of Japan can be traced to less refined and localized practices and that the folk arts, etc., had a vibrant place in Japanese cultural history and continue to have such status.

Genroku period

This is a subset of the Edo period towards the end of the 1600s and the beginning of the 1700s that are particularly rich in the development of various arts. Matsuo Bashō, Chikamatsu Monzaemon, and Ihara Saikaku are all from this era. Confucian learning, new painting styles, short fiction, the kabuki and puppet theaters, a deepening of the haiku tradition are all part of this era. There is a great diversity in content and style in the arts reflecting the greater diversity of consumers of the arts, the result of dynamic economic development (producing a powerful merchant class interested in the arts, which expands patronage beyond warlords and samurai) and earlier political changes (the country was unified and stabilized around 1600).

From Kodansha's Encyclopedia of Japan:

Genroku, the era name (nengō) for the years 1688-1704, is commonly used to refer to the entire rule of the fifth Tokugawa shōgun, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, from 1680 to 1709. It is sometimes used even more broadly to include the flowering of culture, especially among the townsmen (chōnin), from the middle of the 17th to the middle of the 18th centuries.

...

There was also an increase in literacy among merchants, other urban residents, and prosperous farmers. The increase in agricultural productivity and the quickening of commerce in the 17th century were accompanied by the rapid growth of cities, in particular Kyōto, Edo (now Tōkyō), and Ōsaka. As unprecedented affluence came to a larger number of merchants and artisans of the cities, their demand for goods and services stimulated the development of new styles of clothing, entertainment, and arts tailored to their tastes. Unlike the samurai, who were disciplined by an obligation to perform military and administrative service, urban commoners were free to devote themselves to making and spending money. Their pastimes were less restrained and their tastes less informed by tradition. While Nō was considered the form of drama appropriate to the samurai class, kabuki and puppet theater, which developed from the early 17th century, were shaped increasingly to chōnin audiences, and the Genroku era is celebrated as the golden age of both types of theater.

genre

In the case of premodern Japanese literature, "genre" is a way of grouping various texts that appear similar. This is different that, as an author, experiencing writerly constraints because one is working within a particular genre (parody, horror, detective novel, romance novel, etc.) Genre help complete the reading process because the reader understands that, given a particular genre, an interpretation should go a certain direction. (For example, comments in comic modes often should not be taken at face value. In horror stories, "Trust me" often means just the opposite.) So, when trying to recover meanings from premodern texts that resemble how they meant to readers of the time, it is important to consider whether the author is working under the notion of a particular genre and whether the author expects the reader to know that. Generally speaking, in prose works, there is a lot of mixing and matching going on, with portions that seem more like narrative fiction, others that seem like autobiographical writing, others that seem closer to poem collections—all within the same work. That a prose work should be purely of a single genre is not a dominant idea. Poetry was more strict about this.

Major genres that we cover in this class, usually:

- waka (和歌, poem form, from before Nara period)

- renga/linked-verse (連歌, poem form, from Muromachi period)

- haiku (hokku) (俳句/発句, poem form, from Edo period)

- haibun (俳文, prose form with haiku, from Edo period)

- uta-monogatari (歌物語, poem plus prose form, from Heian period)

- setsuwa/legends (説話, prose form, from before Nara period)

- monogatari (物語, prose form, depends, as an oral tradition from very early times but in a more strict sense of onnade narrative fiction, then from the Heian period), includes gunki monogatari (military tales)

- nikki (日記, prose form, if we are talking about not just any sort of dairy but quasi-autobiographical memoirs written by aristocratic women, then from the Heian period)

- recluse literature/inja bungaku (隠者文学, prose form, in a sense from the Heian period but is in full stride from the Muromachi period)

- zuihitsu/miscellaneous writings (随筆, prose form, from the Heian period)

- yōkyoku/Nō drama (謡曲, drama form, from the Muromachi period)

- bunraku, ningyō jōruri/puppet theater (文楽、人形浄瑠璃, drama form, from the Edo period)

I also teach from the perspective of these "groups" of texts. (There are some miscellaneous texts strewn about; these are the main groups.) Here is a list, as it is in my head while lecturing, listed more or less in chronological order. Some texts fall into more than one category, depending on what the topic at hand is:

- poetry: waka, renga / linked-verse, haiku but I also think of The Tale of Genji as loosely affiliated with waka-esque aesthetics and narrative progression, view uta-monogatari (such as Tales of Ise) also in this light and include haibun (such as Bashō's Narrow Road to the Deep North).

- onnade literature of the Heian period, written by mid-level aristocratic women primarily for others of their same gender and social status

- Kamakura and Muromachi texts written by men for a diverse audience that seem particularly invested in Buddhist principles: The Tale of Heike, Hōjōki, Essays in Idleness, Nō drama. These are all written in mixed Japanese-Chinese script (except the Hōjōki, which is in katakana but matches the others in terms of lexicon and style).

- Northern Hills / Eastern Hills Muromachi texts such as Nō drama and Nō treatises, some linked-verse poetic tracts, writings about wabi-sabi all have a similar, rarified, highly philosophical view to them.

- Genroku texts: the plays of Chikamatsu and the short fiction of Ihara Saikaku take similar settings and are trying to appeal to a similar readership / audience, despite their thematic and other differences.

ghosts: see spirits

gunki monogatari ("military tales"), a genre

Beginning with the collapse of the complete grip that the Heian aristocrats had on the imperial government that was located in Heian, in other words, with the end of the Heian period, Japan experienced widespread military conflict for many centuries—from around 1150 until 1600 though some periods were more calm than others. These wars became the stuff of legend, story, drama, painting and so on. The genre "military tales" is one of these. They are written in mixed Japanese-Chinese prose and are narratives of bravery, treachery, military skill, love and loss in the context of the wars of the Kamakura and Muromachi periods. The Tale of Heike is our primary example. I have also mentioned Yoshitsune (Gikeiki, 義経記, Muromachi period, which focuses on Minamoto no Yoshitsune). Taiheiki (太平記, late 14th c.) i is also famous and has a full English translation.

H (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

❖ haibun

From Kodansha's Encyclopedia of Japan: "Brief, informal essays, usually light in tone [although Bashō's Narrow Road to the Deep North is a notable exception] and commonplace in theme, which flourished during the Edo period (1600-1868). The typical haibun begins with a short title followed by a prose text and generally ends with a haiku that derives from or recapitulates the sense of the prose. Compared to earlier prose genres, haibun displayed greater freedom in its use of vocabulary, and its range of subject matter included everyday objects and occurrences that had traditionally been shunned in Japanese literature. Since it is essentially a medium of the haiku poet, haibun shares certain haiku characteristics: ellipsis, suggestion, and the use of classical allusion."

Pairing poems with prose is not new with haibun. We have studied this form already as uta-monogatari (poem-tales).

(I have emphasized some point with green font but this term is not on the testable list.)

haikai: see haiku

haiku (poem form, “unusual verse” 俳句)

A poem form with this syllabic cadence and number of "lines": 5-7-5 (although deviation is accepted).

Traditional haiku require 1) a kigo (“season word” 季語) and 2) usually a “cutting word” (kireji 切れ字, either a grammar particle that is used for emphasis or a grammar form that creates a pause or stop) that inserts some sort of discontinuity in the first portion of the poem with the following portion. Thus, in theyr traditional form, haiku are tied to a specific composition time (on a seasonal calendar) and place, on the one hand, and require poetic imaginative effort on the part of the reader to complete the poem (working with its discontinuity).

Haiku are extremely compact. The best haiku are nearly perfectly concise with a sense that no aspect could be further shortened effectively.

Haiku evolved from the linked verse (renga, 連歌) tradition where the initial three lines (5-7-5) were expected to be able to stand on their own as an independent poem. There is no clear start point for haiku since, in one sense, they “existed” as a component of the longer linked verse, a practice that began in the 12th century but reached full power in the 15th century. Some would like to identify the true start of haiku with Bashō (mid- to late 17th century), since he “elevated” the practice to a serious art. However, in a sense that is a circular argument since it predefines haiku as a serious art form then offers an artist who composed in that mode.

Until recently, haiku were called hokku (“initial verse” 発句).

Heian period (794–1185)

Core information:

Names: 平安時代, sometimes referred to as "High Classical Period", "Classical Period", the Fujiwara era/culture or Fujiwara Regency culture (藤原文化). (*Note: from 694–710 the capital of Japan was at a geographic location called Fujiwara. Some academic fields, which name Japanese historical eras by capital location, have a "Fujiwara Era". This does NOT refer to Heian Japan.)

I have split the Heian period into two subperiods, using the Kokinshū as a border, to emphasize the change in script from manyogana to woman's hand. This is one way to note the shift from using China as a model to developing more indigenous cultural content but it should not be seen as "game-changing". Important, yes, but not a clear demarcation. I just feel the Heian period is so long it is wise to split it for this class.

Heian One (a few major texts)

- Nihon ryōiki, ca 824

(Man'yōshū, is mid-8th c., Nara)

Transitional events

Relations with China:

- Serious decline of Tang, esp. after Huang Chao Rebellion (874-884).

- Practice of sending emissaries to China is discontinued in 894.

- Tang dynasty ends 907.

Shift towards onnade script in 880s (via records of poem events–utaawase)

Submission of the Kokinshū to the emperor, ca. 905

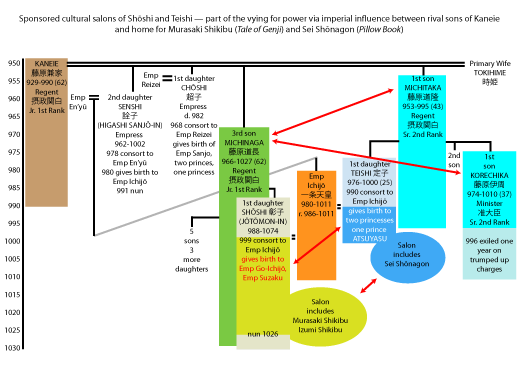

rise of cultural salons that follows increased marriage-politics strategies

Heian Two (a few major texts)

- Kokinshū, ca 905

- Tosa Diary, ca 935

- Pillow Book, ca 1001

- Tale of Genji, ca 1010

Hume thumbnail: "Capital moved to Heian. Beginning of domination of Fujiwara family at court. Founding of Tendai and Shingon schools of Buddhism. Publication of Kokinshu (905) and Tale of Genji (1010). Period of great cultural and artistic flowering."

Major literary works of this period, from the perspective of J7A, all are from Heian Two: The Tale of Genji, Pillow Book, Kokin waka shū, journals and memoirs by aristocratic women (Tosa Diary [written by a man taking on the persona of a woman], Kagerō Diary, Izumi Shikibu Diary, Murasaki Shikibu Diary, Sarashina Diary [English translation title: As I Crossed a Bridge of Dreams])

Additional information for those wanting to explore:

My eBrary folder: (Wallace's) Books of Note: Heian Period

Which includes Ivo Smits, "The Way of the Literati: Chinese Learning and Literary Practice in Mid-Heian Japan", in Heian Japan: Centers and Peripheries, edited by Mikael S. Adolphson, Stacie Matsumoto and Edward Kamens (U of Hawai'i P, 2007). Argues for greater importance to be placed on literary activities that are NOT part of the onnade literary group.

Online:

- My rating of the wiki article "Heian Period" from perspective of J7A (culture first, politics second): 3 out of 10.

- Sites I've selected out of the top 30 Google search hits for "Heian period" that I think are reasonably good:

- From Penn State Univ, HIST 172 (2008) history course that emphasizes culture: Chapter Three: The Heian Period Aristocrats

- From Japan Reference (JREF—I have no idea who these people are): Heian Period 平安時代

Other works:

- Lamarre, Thomas. Uncovering Heian Japan: An Archaeology of Sensation and Inscription. Duke UP, 2000.

Heike monogatari

Name: 平家物語, "Tale of [the] Heike". In translation usually as: "Tale of Heike"

Date of composition: 1371 (in a widely accepted version, but based on nearly two centuries of oral tradition, and there are 100+ versions of the story of the Heike)

Author: Kakuichi (明石覚一、覚一検校), a biwa hōshi

Genre: gunki monogatari (military tale)

Script used: mixed Chinese-Japanese prose

"The most important of the Kamakura (1185-1333) and Muromachi (1333-1568) period prose tales known as gunki monogatari, or war tales. It deals with the short heyday of the Taira family (the 20 years following the Hōgen Disturbance (1156) and the Heiji Disturbance (1160), when they not only defeated their rivals, the Minamoto family, but also ousted the Fujiwara family from its dominant position at court) and the five years of the Taira-Minamoto War [which they lose]. The war began with the Minamoto rising again in 1180 and ended with the crushing defeat of the Taira in 1185. The tale divides into roughly three parts. The central figure in the first is Taira no Kiyomori. Arrogant, evil, and ruthless, he is above all so consumed by the fires of hatred for the Minamoto that he dies in agony, his feverish body beyond all cooling, even when he is immersed in water. The main figures of the second and third parts are generals on the Minamoto side, first Minamoto no Yoshinaka and then, after his death, the heroic Minamoto no Yoshitsune, a youthful military genius wrongly suspected of treachery by his elder brother Minamoto no Yoritomo." (Encyclopedia of Japan, Kodansha)

The opening paragraph of this story is one of the most famous in Japanese literature and sets well the theme of the work, that the proud and powerful will fall (in accordance with the law of Buddha).

The last portion focuses on the end of the Taira clan and the very final chapter, "The Initiates" chapter, is set post-war and is in the mood of recollection of earlier events.

Hitomaro: see Kakinomoto no Hitomaro

Hōjōki

Name: 方丈記, "Record at [my] ten-feet by ten-feet [hut]". In McCullough as: "An Account of My Hermitage"

Date of composition: 1212

Author: Kamo no Chōmei (鴨長明), an aristocrat turned monk

Genre: by one measure zuihitsu but probably better just to think of it as inja bungaku (隠者文学, recluse literature), a type of reflective writing done by those (either theoretically or literally) distant from common society about life and principles (Buddhist and Confucian)

Script used: mixed Chinese-Japanese prose

This is a very famous, highly polished essay that takes houses as a metaphor to talk about the Buddhist truth of impermanence and suffering. It recounts major disasters of the time, the suffering that they caused, and the writer's gradual reduction of the size of his own dwelling, ending with a very honest self-evaluation that despite his best efforts, he is still not very good at practicing Buddhism. It's first paragraph is so famous, I list it here. Please be familiar with it and be able to relate ideas of impermanence and the foolishness of humans who do not see Buddhist truth.

"The waters of a flowing stream are ever present but never the same; the bubbles in a quiet pool disappear and form but never endure for long. So it is with men and their dwellings in the world. The houses of the high and the low seem to last for generation after generation, standing with ridgepoles aligned and roof-tiles jostling in the magnificent imperial capital, but investigation reveals that few of them existed in the past. In some cases, a building that burned last year has been replaced this year; in others, a great house has given way to a small one. And it is the same with the occupants." (McCullough, translation)

The full Hōjōki is in McCullough's anthology. Please be familiar with the introduction to it.

honkadori (本歌取, allusive variation)

Poetic technique especially associated with the Shin Kokinshū: To include in one's own poem one or more lines from an older poem in order to enliven the content and aesthetic effect belonging to that older poem, while also making one's own poem more complex and resonant of content. "Honkadori" literally means "the drawing from an origin / foundation poem" and is often in English translated as "allusion" (though this is inaccurate), "allusive variation" (better), "taking from a foundation poem," etc.

Example. The Shin Kokinshū poem ほのぼのと春こそ空に来にけらし天の香具山霞たなびく (Steven Carter translation: Dimly, only dimly— / But, yes, spring has come at last / To the sky above: / In haze trailing on the slopes / Of Kagu's Heavenly Hill.) is based on a Man'yōshū poem: 久方の天の香具山この夕霞たなびく春立つらしも (Edwin Cranston, trans. A Waka Anthology Vol. 1, Poem #397 by Hitomaro: "On sun-radiant / Heavenly Mount Kagu's slopes / In the evening light / Bands of haze are drifting— / Spring must be here at last!".) The change is in the subjective state of the poet: the older poem emphasized the vast sky and the poet's appreciation of its grandeur, the newer poem makes the discovery of spring a less distinct, more subtle moment.

I (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

Ihara Saikaku (井原西鶴, 1642-1693)

From Kodansha's Encyclopedia of Japan: "Poet and writer of popular fiction whose novels and stories are now ranked among the classics of Japanese literature. ... He was born in Ōsaka. After the death of his young wife in 1675 he devoted himself to his flourishing career as a poet of haikai (comic linked verse...[JRW: in the Danrin style]), traveling widely and continuing to frequent theaters and pleasure quarters. [JRW: After the death of his haikai teacher when he was 40, he turned to writing in the prose genre ukiyo-zōshi (浮世草子), a short story form that usually involved themes related to sexual play, desire and love.] At 40, Saikaku published his first work of prose fiction, Kōshoku ichidai otoko (1682; tr The Life of an Amorous Man, 1964). Its great success made him a hardworking professional writer, the author of some two dozen books during the last decade of his life."

Saikaku has an excellence sense of language; it is colorful, at times quite vernacular, and witty but expert in classical allusions as well. He is known to have written 23,500 verses in a single 24 hour period. Saikaku has a way of making declarative statements in an authoritative way that makes the reader wonder if he is serious or playing with the reader, or both: "Love knows no darkness" 恋は闇といふことを知らず, is, to me, such an example.

Saikaku should be considered one of the three great writers of the Genroku period. (The other two are Chikamatsu Monzaemon, the playwright, and Matsuo Bashō, the haiku master.) An Osaka man, he was fond of theater and knew the world of the pleasure quarters well. He was writing haiku at the same time as Bashō (who was born two years after Saikaku was born); he turned to fiction while Bashō was deepening his expressions of sabi and karumi. Bashō, I imagine, would have nothing to do with him. (Not only was one operating mostly in Edo and the other in Osaka, we can also consider Bashō's devotion to Confucian ethics, and his somber approach to poem composition. Recall his fictional reaction to the traveling women entertainers we read of in Narrow Road.) Saikaku dies in 1693 still writing furiously; Bashō dies in 1694 still writing furiously, including polishing his Narrow Road. Chikamatsu's dates are 1653-1724, so he is about ten years later than these two. He lives about three decades past them. Chikamatsu's artistic success as a playwright begins more or less contemporaneous with Bashō's serious exploration of sabi in haiku and Saikaku's fiction writing career.

illustrated scrolls: see emakimono

Issa: see Kobayashi Issa

Izumi Shikibu: see under Izumi Shikibu nikki

Izumi Shikibu nikki

- Name: 和泉式部日記 which means "Izumi Shikibu's Diary" ("Shikibu" is a title not a given name) but since this is written in third person, with the main character referred to as "the woman" (onna 女), and because another version of the title is Izumi Shikibu monogatari ("Story of Izumi Shikibu"), to think of this as a "diary" in the Western sense is misleading.

- Date of composition: ca. 1007 (Heian Two)

- Author: likely to be Izumi Shikibu but there are other theories

- Genre: nikki more or less, but written very much like a monogatari ("tale")

- Script used: onnade

Tells the story of the first ten months of a romantic affair with a prince, the younger brother of another prince, whom she had loved for about a year when he died suddenly. This prince also dies in his twenties (not told in the diary) and the work was probably written shortly after that death. The work is known for its extensive exchange of love poems between the two.

Izumi Shikibu (和泉式部, “Lady Izumi") is a Heian period poet known for her love poems and romances. A member of Shōshi’s salon, which included Murasaki Shikibu. Protagonist (and likely author) of Izumi Shikibu's Diary / Izumi Shikibu’s Story (Izumi Shikibu nikki). A “provincial governor’s daughter” (= member of the zuryō class).

J (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

jiriki-"self" power: see Buddhist reforms of the Kamakura period

journals: see nikki

K (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

kabuki (歌舞伎), a type of theater

From Kodansha's Encyclopedia of Japan: "One of the three major classical theaters of Japan, together with the Nō and the bunraku puppet theater. Kabuki began in the early 17th century as a kind of variety show performed by troupes of itinerant entertainers. By the Genroku era (1688-1704), it had achieved its first flowering as a mature theater, and it continued, through much of the Edo period (1600-1868), to be the most popular form of stage entertainment." Kabuki was particularly active in Edo (while Osaka was the site of bunraku theater).

Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (柿本人麻呂, late 7th c., active 689–700)

Name: He is sometimes referred to simply as "Hitomaro".

Man'yōshū poet, proficient in both chōka and waka. Presented in class as one of the main poets of the Man'yōshū and important to the development of lyricism within the Japanese poet tradition. Ian Levy, in the work assigned, might overstate his contribute somewhat, but we are mostly following his analysis in this class.

Kamakura Period

Core information:

Names: 鎌倉時代, sometimes referred to as "Medieval Period" but this a misnomer. In Japanese secondary sources this is part of the "Middle Period" (中世).

One of the important defining characteristics of this period is less a positive value (something it is) than a negative value (something it is not); it is not like the Heian period. Then, there was mainly one group of cultural elite, sharing the same space (the capital of Heian). Now that centralized and somewhat cloistered group has had to cede power to military leaders. The power centers are, mainly, split between the aristocrats of Heian and the military leaders of Kamakura. For example, in a civil law suit, one often had to win in both courts. Things were complicated. Groups are fracturing into even smaller groups and alliances are complex. While all of this centrifugal force would tend to, one would think, create diversity in the cultural arts, in truth the aristocrats are still the primary arbitrators of taste and aesthetic ideas, with military social wannabes trying to assume aristocrat manners and sensibilities.

Two factors, related, do induce substantial changes: the decline of the literary salons as the primary location of the production of prose and, on an entirely different level, Japan's reconnection with the continent. The first leads to a demise of fiction being written by women and their onnade literature. Most prose is now written by men, for mixed audiences, using mixed Chinese-Japanese. Confessions of Lady Nijo and a few other premodern prose works will be written by women after the end of the Heian period but, for the most part, they disappear from the scene except in the arena of poetry. We will have to wait until the 1800s to see excellent woman's literature again. The second factor leads to considerable influence from China in many of the arts and, importantly, is an integral element in the important Buddhist reforms of this time.

Japan is at war for much of the Kamakura period.

The Shin-Kokinshu, The Tale of Heike, Hojoki and Essay in Idleness are probably the most important literary works from this time.

Additional information for those wanting to explore:

My eBrary folder: (Wallace's) Books of Note: Kamakura Period

Not a very impressive collection, however.

Online:

- My rating of the wiki article "Heian Period" from perspective of J7A (culture first, politics second): 4 out of 10.

- Sites I've selected out of the top 30 Google search hits for "Kamakura period" that I think are reasonably good:

- First, I was surprised to see the Cambridge History of Japan online. This is a major, multivolume work, relatively new. It is a good resource if the whole production is online. This link is to a chapter on Kamakura Buddhism: Chapter 12: Buddhism in the Kamakura period

- Sites with general history narratives that have more than the usual amount of cultural information. All have lots of links.

- factsanddetails.com

- lakelandschools.us

- bookrags (has one of the better biblio list)

- A pretty good overview of Kamakura Buddhist reforms: buddhanet

- More for art:

- On social hierarchies: facts-about-japan.com

kana-zōshi (仮名草子), a genre

no content yet

karumi (aesthetic term: "lightness")

As defined by Makoto Ueda in Basho and His Interpreters: "A poetic idea advocated by Bashō in the last years of his life. Literally meaning 'lightness,' [軽み] it points toward a simple, plain beauty that emerges when the poem finds his theme in familiar things and expresses it in artless language. Bashō tried to teach the concept to his students by giving such directives as 'Simply observe what children do' and 'eat vegetable soup rather than duck stew.'"

Here is a second definition. I include this NOT because I think it is accurate but because it is a good representative of misreadings of Basho (in my opinion) when he is presented as one wise in Zen. However, the quote from Bashō is accurate, widely quoted, and a very good definition of karumi.

As defined by Lucien Stryk, On Love and Barley, "Towards the end of his life Basho cautioned fellow haiku poets to rid their minds of superficiality by means of what he called karumi (lightness). This quality, so important to all arts linked to Zen (Basho had become a monk), is the artistic expression of non-attachment, the result of calm realization of profoundly felt truths. Here, from a preface to one of his works, is how the poet pictures karumi: 'In my view a good poem is one in which the form of the verse, and the joining of its two parts, seem light as a shallow river flowing over its sandy bed.'"

Here is an example of a poem by Bashō that he said has a "tone of karumi" (trans. by Ueda in Basho and His Interpreters):

under the tree

soup, fish salad, and all—

cherry blossoms

ki no moto ni shiru mo namasu mo sakura kana

kigo (season word): see haiku

kireji (cutting word): see haiku

Ki no Tsurayuki (紀貫之, 872?-945)

Famous poet and critic from Heian Two period.

Tsurayuki is one of the most important figures in the history of Japanese poetry and his poems are excellent. However, it is his dynamic involvment in activities related to literature that are valued the mostly highly.

- Lead editor of the Kokinshū (ca. 905), and author of its two famous prefaces.

- Since the Kokinshū became something of a gold standard for judging poetic quality, his contribution to the history of Japanese literature is very important.

- Promoted: 1) the importance of poetry and 2) the importance of poetry in woman's hand, and 3) was influential in determining what should be considered a superior poem.

- Author of Tosa Diary (Tosa nikki, 935) which official stands at the head of the genre of Heian period private memoirs and journals (Ocho nikki bungaku 王朝日記文学) written almost entirely by women. At the beginning of this journal he states that he will write it "as if a woman".

Kobayashi Issa (小林一茶, 1763-1827)

Kobayashi Issa (1763-1827, active a little more than one hundred years after Bashō; his writing career does not really overlap that of Buson) is know for his sense of humor and his love for the small and charming, particularly animals. Issa's poems are accessible and he is very popular among Japanese lovers of poetry today. Issa, whose poems often have a sense of optimism about them, actually suffered terribly in his own family life. Among his many troubles, all of his children as well as his wife predeceased him.

From Kodansha's Encyclopedia of Japan: "In 1814 Issa married a ... woman named Kiku. Four children were born in quick succession, but none of them lived long. The birth and death of his second child, Sato, inspired Issa to write Oraga haru (1820; tr The Year of My Life, 1972), the best known of all his works; it was written in haibun ([俳文] haiku mixed with prose passages). ... His style is characterized by a bold acceptance of down-to-earth language, by the introduction of animal images, by the use of personification and the free exercise of a comic spirit, and by the frequent expression of a stepson mentality and an obsession with poverty. These unconventional elements were, however, combined with the high seriousness Issa inherited from Bashō."

koi ("longing")

The word "love" is not used much in premodern Japanese texts. It is expressed through action and through less direct language. The love of a parent for one's child is probably considered the strongest type of love but in the texts we read for this class, love most frequently either means strong romantic feelings of attachment and desire (between two individuals) and powerful devotion to one's leader. The shape of love is often that of longing (regretting the absence of one's beloved), sacrifice (placing one's beloved ahead of one's need, usually without telling the partner about it), obligation (feeling strongly, sometimes painfully what one should do for one's lover), and thoughtfulness (empathetic understanding of another's need, frequent reflection on another's situation and so forth). Christian principles such as "selfless love" are not strong and thinking about love from one's own perspective rather than that of the beloved is very common. In this vein, koi (longing) frequently appears as the defining characteristic of a relationship (not, for example, exuberance or joy in being in love). The word "ai" (love) existed in premodern Japan but isn't widely used to describe romantic feelings. "Koi" and "ai" still have a difference of nuance to them today, with "ai" feeling a bit more "foreign" as a term. In modern Japan it is more common to say "I really like you" (dai suki desu) than "I love you" (ai shite imasu) but expressions are ever-changing. It is common, too, to hear "I'm in love" (koi o shite imasu) when talking to someone else about one's own situation. "Koi-bito" (恋人) is a common term for "lover."

Kojiki

- Name: 古事記, "Record of Ancient Events", we use the romanized title in J7A.

- Date of composition: 712

- Author: unknown

- Genre: chronicle / historical narrative

- Script used: sinified Japanese

Comments:

Together with the Nihon shoki (720) considered one of the earliest literary prose works of Japan. Both are "histories" of early Japan, beginning with mythical times. Both implicitly support the Yamato claim to governance (establish an imperial line that supports the leaders of Nara Japan).

There are many famous stories in the Kojiki (which usually appear in the Nihon shoki as well). For example: the meeting of Izanami and Izanagi which leads to the birth of the Japanese islands; the sun goddess Amaterasu hiding inside a cave after the misbehavior of her brother Susano-o.

Both the Kojiki and the Nihon shoki have very complicated script systems that used Chinese characters to record Japan and sinified-Japanese. The hiragana script did not yet exist. Another very famous literary work that also uses a similar complicated script system is the Man'yōshū (first Japanese poem anthology, mid-8th century).

Kokin waka shū

- Name: 古今和歌集 "Collection of waka ancient and new". Often called just Kokinshū or even just Kokin. The "old and new" indicates an honoring of what has come before but an interest in also honoring current poetic practices, the leading edge so-to-speak. It is a fairly typical component of titles.

- Date of composition: I use 905 for this class but the truth is a bit more complicated. It is likely that portions were added or amended after that date.

- Author: The primary complier is Ki no Tsurayuki although he did not work alone.

- Genre: waka

- Script [script] used: onnade (except that there are two prefaces and one of them is in magana)

The Kokinshū set something of a gold standard for aesthetic directions, stands at the beginning of a long and successful tradition of poem collections compiled by imperial command, and, by using onnade, established that script at the center of literary composition practices.

In terms of technique, it is known for kakekotoba (掛詞, pivot words) and engo (縁語, related words). It absolutely never departs from diction the of miyabi (雅, courtly elegance) and tends towards indirect expressions. Word-crafting is important to Kokin poets. Many poems have a type of contrived and precious logic that is often called "wit" or "wit built around poetic conceits". For example:

KKS 1. Written when the first day of spring came within the old year.

toshi no uchi ni ........ spring is here before

haru wa kinikeri ........ year's end when New Year's Day has

hitotose o ........ not yet come around

kozo to ya iwan ........ what should we call it? is it

kotoshi to ya iwan ........ still last year or is it this?

Online access, generally good:

- In Japanese:

- In English:

http://www.temcauley.staff.shef.ac.uk/kokinshu.shtml

L (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

Lady Nijō: see Towazugatari

laments: see banka

linked verse: see renga (poem form, 連歌)

literary salons: see sponsored cultural salons

Love (romantic love) and Buddhism

Premodern Japanese Buddhism does not provide a sacred space for romantic love or otherwise elevate it to the high status it enjoys in Christianity. It treats sexual desire as just one of the many unenlightened activities the people do, not as a sin. In Heian Japan the Buddhist teaching of impermanence was translated by literature about love as subverting the reliability of love. Romantic relationships are generally taken as likely to be short-lived, marked with suffering, and unreliable.

Love (romantic love) and Confucianism

Confucianism as we see it in premodern Japanese literature does not provide a sacred space for romantic love or otherwise elevate it to the high status it enjoys in Christianity. Romantic love can develop within a proper husband-wife relationship but the relationship can also be stable and productive even without it. Romantic love outside marriage is generally regarded as driven by sexual desire. Sexual desire might be natural but it can be disruptive to social order. Confucianism resists any active that challenges social order and proper relationships. Confucianism defines most relationships as essentially hierarchical in nature and, in the case of male-female relationships this manifested in practice as male superiority. Most of the women we read about do not challenge the ultimate authoritative position of men and do see their role as in support of men. They expect, ideally, proper Confucian reciprocity where the "ruler" is benevolent, protective, and nurturing towards his subject but accept in practice a very distant echo of this benevolence.

Love (romantic love) and Daoism

I mentioned Daoist sexual alchemy in class to subvert the notion that sexual intimacy is an expression of romantic commitment, devotion or tenderness. While these things are not barred from being components, that intercourse is considered necessary for a healthy mental life and is essentially for the benefit of the man is an unspoken background of the world of The Tale of Genji.

Love (romantic love) and the five books of love in the Kokinshū

In the Kokinshū there are about 360 poems collected into five books of love. They represent a significant subset of that collection, about one-third of all poems in the collection. The Kokinshu editor arranged love poems with principles similar to the nature poems, that is as a progression. In the case of the five books of love this progression is Book I - infatuation, one-sided love, declarations of interest. Book II is similar but at a slightly more progressed state of the relationship, with correspondence between the two already happening to some degree. Book III covers the time just prior to the first physical consummation of love through the period where the lovers are meeting frequently or at least wishing to meet frequently. This book includes worries about reputation and whether one's partner is reliable or truly in love, and complaints about not being able to see one's lover. There is not much joy in this book. Books IV and V cover that period when the lover's visits are decreasing in frequency or have stopped. In both cases the poems are mostly by women and have a resigned or lonely or repressed-angry tone to them. The primary difference between the two books is probably a mental one: whether the poet considers the relationship winding down (IV) or over (V).

lyricism

"Lyricism" is a technical term in Western literary criticism. It is also a general term in the English language, where it means something along the lines of beautiful, enthusiastic expression of emotion. (For example, from Webster's: "a quality that expresses deep feelings or emotions in a work of art : an artistically beautiful or expressive quality.") These definitions are not good enough for how I want to use lyricism in J7A. The below comments are core to the course.

Premodern Japanese literature very often places considerable emphasis on emotional content, and this is important to notice.

"Western" readers (readers who have been trained "how to read literature" in an education system that has dominant Western values or who has grown up consuming narratives in whatever form in dominantly Western-values culture—where Western is used very loosely, apologies for that) new to Japanese premodern literature sometime under-notice the importance of teasing out the emotional content that is often represented indirectly or with restraint and which shows an interest in subtle, nuanced emotions and emotional changes in addition to more powerful and easily accessible feelings. "Emotional intelligence" was highly valued among premodern Japanese aristocrat involved in the production and consumption of literary works. In J7A, for most premodern literary texts (poetry or prose), I do not think they have been read well enough if there is no complex understanding, on the part of the student, of the emotional content of the texts.

On the other hand, "Western" readers might "over-enhance" emotions, working from the expectation that good literature should have "impact". Much of premodern literature is not "high octane" in content.

Additionally, Western readers often approach a text with the expectation that great writers are "highly individualistic" and their writing demarcate the writer's unique vision of things. The best premodern writers are individualistic in some way, but in most (though not all cases) the innovations work within traditions, not against traditions, and maintain some connection to the community for which they write.

Reading Japanese premodern literature expertly involves, in part, getting the above balance right.

So, while it is often said that premodern Japanese literature, especially poetry, has a strongly lyrical content, the words "lyrical" and "lyricism" can obfuscate the text if uncritically applied.

Thus, for this course, I give a specific definition. It is a working definition just for J7A. It continues to evolve but it goes something like this:

A tendency in poetry and, as an outgrowth of that, in prose passages, to take a subjective perspective by expressing the poet's or character's emotional response to a situation or scene. The border between the subject (the poet as represented within the poem as the human seeing and reacting to the scene) and the object (the topic of the poem) is sometimes not clear. The complex relationship between soto-uchi should be kept in mind.

Additionally, the response suggested by the poem is not that of an independent poet with a unique vision that s/he is sharing with others, but rather a skilled engagement with collective (sometimes called "banquet") values. The virtuosity of expression and the keen nuances of the response itself work together to display one's education in terms of elegant, emotional intelligence, as defined by that time/era.

Further comments about lyricism, including a stepped discussion of parts of the above, is included elsewhere in assigned materials.

Sugimoto offers and extended and interesting analysis in Michael Sugimoto, "'Western' Lyricism and the Uses of Theory in Premodern Japanese Literature" Comparative Literature Studies 39:4 (2002): 386-408.

M (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

makoto

"sincerity" "uprightness"

... but within a high discourse, an aesthetic context.

For example: "Miyabi was in a sense a negation of the simpler virtues, the plain sincerity (makoto) which MYS poets had possessed and which poets many centuries later were to rediscover." (de Bary, 1958, quoted in Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader, 47) In other words, it vied for a central position in poetics.

Or, "At the center of Onitsura's haiku theory is his statement about truth. [Uejima Onitsura 1660-1738 was one of the outstanding haiku poets of the 17th century.] Everywhere in his writing he uses the word makoto. This term is used in various ways and its meanings is not fixed. However, he uses this term in the sense of sincerity. In his writing entitled Soliloquy, he said, "When one composes a verse and exerts his attention only to rhetoric or phraseology, the sincerity is diminished.' The fact that no artistic effort in the form or no decorative expression in the content [should be present] is Onitsura's idea, which is the way to sincerity." (Kenneth Yasuda, quoted in Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader, 139)

Makura no sōshi

- Name: 枕草子 "A sōshi at the pillow" or "A sōshi of such length as to stack up as high as a pillow." A sōshi is a type of book where the pages are folded and bound together with silk thread rather than rolled into a scroll. Sōshi are considered a more informal book style. "Pillow Book" does not suggest, as it does in English, erotic or highly private content.

- Date of composition: sometime after 1000 with portions perhaps much later.

- Author: Sei Shōnagon (清少納言), a provincial governor's daughter, a lady-in-waiting to Empress Teishi, until her death in 999

- Genre: Usually considered a zuihitsu, it can be seen as a nikki and has sections that are closer to monogatari: 随筆、日記、物語. The short answer for this class will be zuihitsu.

- Script [script] used: onnade

This work is widely loved by Japanese and is known in particular for the wit and liveliness of its author as well as its interesting lists. For historians it has been an important document in trying to ascertain details about court life of the time.

Man'yōshū

- Name: 万葉集 "Collection of Ten-thousand Leaves" where "leaves" is synonymous with "words" (kotonoha ことの葉, kotoba). "Ten-thousand" is typical expression to mean "very many".

- Date of composition: mid-8th century (Nara period)

- Author: final complier is Ōtomo no Yakamochi (大伴家持, 717?–785)

- Genre: primarily waka but includes chōka and some other forms, presented under 20 categories (called "books" or "scrolls" / maki 巻)

- Script used: sinified Japanese (manyōgana 万葉仮名)

Usually considered the first Japanese major collection of poems. It ranks together with the Kokinshū and Shin-Kokinshū as one of the three major collections of waka. It is famous and has had enormous influence on poetic style. As among its many areas of influence, we should include the lyricism embraced and developed by Hitomaro and others. Many of its poems show an affinity to Chinese poetry.

Hitomaro is one of the collection's most important poets. Other excellent poets include the female poet Nukata 額田王 (latter half 7th c., 13 poems), Yamabe no Akahito 山部赤人 (early Nara period, active 724–36, 50 poems), Ōtomo no Tabito 大伴旅人 (665-731, 71 poems), Yamanoue no Okura 山上憶良 (660?-733?, 77 poems), and Ōtomo no Yakamochi 大伴家持 (718?-785, 479 poems—remember that he is in a position of editorial authority).

The Man'yōshū, especially compared to the Kokinshū that follows it about 150 years later, is a large and diverse collection in terms of poetic form, background of individuals included, topics, and regions represented. However, "diverse" should be understood in a premodern sense, not a 21st-century sense.

mappō ("end of Dharma law" 末法)

Also can be thought as "the latter days of the world" "the sinful age" and so on. The idea is based on the Buddhist assertion that the universe cycles through various stages, over very very long periods of time (millions of years) where Buddhism and the practice of Buddhism are in the ascendency or in decline. Mappō indicates the period of decline and is marked by increased suffering, natural disaster, corruption, inability to follow Buddhist faith and so on. Buddhist texts has calculated this period to being in 1052 and during the Kamakura Buddhist reforms, with its political disturbance, famine, plagues and other natural disasters, it was widely considered self-evident that the period had begun.

masurao

"Valiant," "exceptional," used in the ancient period (Nara) to refer to men at court.

Sometimes used by women just to mean "my man" or "man" as in this MSY 4211, (Cranston translating, excerpt):

As the colored leaves of autumn,

She who stood now

In the heartbreaking prime of loveliness

Felt such compassion

For the vows her valiant lovers swore

That she bade farewell

To her father and her mother,

Left her home behind,

And turned her footsteps towards the sea.

A definition by a scholar: "an ethical code of behavior embodied in the Japanese words masurao and masuraogokoro. The word masurao is extremely ancient, and conveys the basic meaning of "man," but usually in a hortatory sense, such as a strong, heroic, or magnificent man. The word masuraogokoro also appears very early in Japanese literature with much the same meaning as masurao. The words denote a socially determined concept of masculinity, the proper, ideal role for which each man should strive. In a narrow sense they are close in meaning to the modern Japanese word otokorashii, "manly". However, the term otokorashii is not an exact synonym because it does not convey as strongly certain ideological and ethical assumptions that came to adhere to the word masuraogokoro." (JSTOR: Manly Virtue and the Quest for Self: The Bildungsroman of Mori Ogai, Dennis Washburn, 13)

Matsuo Bashō (松尾芭蕉, 1644-1694)

1644-94. Edo (Genroku) period haikai master and author of Narrow Road to the Deep North (Oku no hosomichi 奥の細道) and widely loved in Japan for his haiku. He is known for influencing haiku composition towards more solemn and deep themes. His poems are respected in particular for their expressions of sabi. He himself had a deep respect for the traveling monk Saigyō of the Shin-Kokin era and emulated his life by traveling frequently and for great distances. He was highly educated in literature of both his own country and China, was an excellent calligrapher, a good painter, a lover of history, and oversaw a large number of students who enriched and spread the Bashō school of haiku. Towards the end of his life he explored a new aesthetic concept called karumi (lightness).

memoirs: see nikki

michi: see under bushidō

military tales: see gunki monogatari

miyabi (aesthetic term)

"courtly elegance"

雅 is the usual kanji. It is possible that the origin of the word is 宮振り (acting courtly) or 御屋ぶり (acting as if of the royal chambers). (日本国語大辞典)

Miyabi, in its basic meaning, is not a particularly difficult concept. It refers to artistic conventions, diction and other speech patterns, various behaviors and attitudes that reinforce the concept of "beauty associated with the court". It is thus in a sense a quasi-ethical or anyway behavior-based construct. Acting in accordance with miyabi shows one's understanding of, and thus likely membership in, the aristocracy—usually at high levels. Being able to perceive miyabi in objects that have it shows one's education and training in the same ways of thinking, perceiving and behaving.

What I would like you to keep in mind is that miyabi is a keynote to nearly all the cultural objects we encounter, and extends into the heart to regulate feelings. Miyabi carries with it a suggestion of polished or regulated or self-aware or "restrained" (in a sense) gorgeousness or elegance, plus markers that indicate education, wealth and power. These basic elements remain in the later, and much more difficult aesthetic formulations of yūgen (with its strongest formulation in Noh drama) and sabi (with its strongest formulation in cha no yu, the tea ceremony).

Ways that the concept of miyabi affects the interpretation of literature:

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE

Full understanding of miyabi as a necessary element in true emotional intelligence (as defined by Heian aristrocrats at least)

MIYABI & POWER

Miyabi indicates closeness to power group or membership in them.

Miyabi can reframe an inappropriate or even criminal emotion, thought or act, in a way that seems to protect it from negative repercussions, in other words, as “cover” (either automatically present or deployed on purpose)

IMPACT ON DISCOURSE CONTENT

Miyabi almost insists on indirect expression or partial expression or round-about expression of things.

Miyabi as censoring or supressing. Miyabi insists on excluding certain words, phrases, even topics. This has a very large, I think we should say enormous, impact on discourse content. You need to work to bring these missing pieces back into the narrative.

GROUPNESS

Having or not having miyabi behavior or knowledge as marking membership in a group, or non-membership.

Miyabi carrying with it social norms and pressure of conformity to the group.

MONO NO AWARE

Miyabi as important to the general emotional or aesthetic or conceptual context for mono no aware.

•

If curious, "miyabi" was often written just in onnada as みやび, and in most formal discussions of it it is written 雅 (as noted above), but it does echo with miya 宮 and bi 美. Here are some very old ways of writing "miyabi":

日本書紀 (720): 藻(ミヤヒ)、風姿(ミヤヒ)

神楽歌〔9C後〕美哉斐(ミヤビ)

mono no aware

This complex term has been described from various points of view in various ways to try to capture is extensive meanings. See the PPT but also review notes. Here, I would just add: don't forget that I emphasize the importance of time for many of the "aware" moments of our stories, that I said reading large stretches of material was necessary to understand it (another way of saying that the sweep of time can be very important). Also, here is a thumbnail definition from Princeton Companion to Japanese Literature. It is meant not as a substitute but to jog your memory: "The deep feelings inherent in, or felt from the world and experiences of it. In early classical times "aware" might be an exclamation of joy or other intense feeling, but later came to designate sadder and even tragic feeling. Both the source or occasion of such feeling and the response to the source are meant."

mononoke: see spirits

Motoori Norinaga (本居宣長, 1730-1801)

Motoori was one of the dominant scholars of the Edo period. He wrote important commentaries on the Kojiki and The Tale of Genji. However, our interest in him for J7A is specific: he reframed the way The Tale of Genji was considered, elevating its position among the other canonical texts and emphasizing mono no aware. This is a good example of remember that premodern texts exists, for us, within a scholarly context and that how we read them and think of them is heavily colored by how scholars in the past have done so.

mujōkan

Name: 無常観 (contemplation of the Buddhist truth that all is ever-changing) and 無常感 (feeling / experiencing that all is ever-changing, sense of uncertainty)

Mujō is a Buddhist technical term that designates the "not-permanent" (無,常) essence of all things, their emptiness. From that is derived the Buddhist position that everything is always changing. From that is the claim that this world as we experience it is a world of suffering—not only because suffering actually exists (natural death, a forest fire, whatever) but also, and more importantly to the literature we read, the human (unenlightened) subjective, emotional response to change (dukkha) is to suffer.

Mujōkan, an awareness that things are not permanent, that you cannot count on the good and the beautiful, even love between two people, to endure, is a deep-running sense in Japanese culture. It does have counter-balancing cultural concepts and it would be radically incorrect to think of the Japanese or their art as working solely under the dark sign of a sad hyper-awareness of ephemerality. Still, it is a way of thinking that has provided rich thought, including literary expression, and is helpful for interpreting some cultural expressions.

Bottom line, a full and accurate, objective, understanding of mujō leads the Buddhist practitioner towards serious commitment to his or her religious practice and is a precondition to enlightenment. But, as we encounter it in premodern Japanese literature, is takes many forms. It provides a vocabulary for anxiety about a relationship or one's fate more generally (an approach widely used in Tale of Genji; it can provide a transcendent perspective (an approach particularly strong in post-Buddhist reform texts such as Hōjōki and Tale of Heike), and so on. the segment in this course on lyricism, a tendency to take a subjection position and express an emotional response to a situation, is included in part to help explain this gravitation towards narrative a troubling awareness of mujōkan.

The idea that cherry blossoms are painful because of the combination of their exquisite beauty and short-lived presence is built upon this concept and has been part of Japanese culture since the Kokin period. Tosa nikki Day 9: "If ours were a world / in which flowering cherry tress / were never in bloom, / what tranquility would bless / the human heart in springtime! (yo no naka ni taete sakura no sakazaraba haru no kokoro wa nodokekaramashi)"

Murasaki Shikibu: see under Tale of Genji

Murasaki Shikibu nikki: see under Tale of Genji

Muromachi period (1333-1568)

1333-1568. The Muromachi period is a time of warfare but also major economic advances. Buddhist influence is at its peak as well, and is widely evident in the arts from this period. Two particularly rich stretches of time within this period are the Northern Hills culture period and the Eastern Hills culture period. The former is the forum for the development of Noh drama; the latter for the tea ceremony.

musubi: see under en

N (A-D | E-H | I-L | M-P | Q-T | U-Z)

Nara period (710-794)

Core information:

Names: 奈良時代, sometimes referred to as the Tempyō culture (天平文化).

Hume thumbnail: "Capital moved from Asuka to northern Nara region. Buddhism becomes court religion. Three important literary works, Kojiki (712), Nihon shoki (720), and Man'yōshū (777)."

The Nara period is a centralized government with a fully strengthened imperial line. Contact with Tang China is regular—architecture, urban design, government offices, documents and so forth all reflect this. Buddhism extends its influence. The country itself (as in from corner-to-corner) is not widely developed, but within localized urban centers culture is very advanced.

From the point of view of J7A:

- this is NOT yet a government under the grip of the Fujiwara family and the location of the government is not yet Heian-kyō; it is Heijō-kyō (present day Nara).

- the fantastic and massive imperial anthology Man'yōshū is from this period, as are the "histories" Kojiki and Nihon shoki.

Additional information for those wanting to explore:

My eBrary folder: (Wallace's) Books of Note: Nara period