EA105 Course Basics

Some key terms

On the Announcements Page is a link to key concepts & terms that are relevant to many of my courses. These have specific definitions, not common sense definitions, so it is beneficial to you if read them. Currently (May 2013—but the terms page is constantly updated), terms particularly relevant to the conceptual aspect of this class (not assignment instructions) are:

analysis, compare, careful reading, compound statements, content / content-rich, instance, overreach, relate, romance, story / story's world, term slippage, values / worldviews

Definition of "love" for this course

"Love" (romance) for the purposes of this class has a specific, if complex, definition. See "romance" under the terms sidebar link on the Announcements Page.

What this course is not

This is not a primer on how to be romantic, how to be a better partner in love, nor is it sex education, nor is it a let's watch "cool Asian films" class.

Primary course theme & goals

Course theme: The interpretation of East Asian narrated romance (premodern and modern) through awareness of worldviews and select core values as context.

Main course goals:

1) Deeper and more accurate interpretations of East Asian romantic narratives premodern and modern.

2) Vertical analysis (contemporary narratives compared to historical traditions) — As a necessary activity in working towards Goal #1, we try to take a measure of the place of premodern values (relevant to romance) in instances of modern East Asian cinema (with speculation of what this might suggest of society).

3) Horizontal analysis (comparison to one another of values in film and beyond of China, Korea and Japan) — As a derivative of #2, a comparison of China, Korea and Japan, finding differences and similarities worth noting.

Primary means to the goals: Disciplined interpretation & analysis constrained to specific method and rules that consider narratives within cultural context. Analysis is carried out through individual, team, and classwide exercises, reports, presentations & discussions. The class, therefore, is part lecture, part discussion and part workshop.

See the right-hand sidebar of any of our course Web pages for a repeat of these paragraphs.

Secondary course goals

I would like you to have more sophistication in thinking of the relationship of thought-systems and traditions to how we view things, make decisions, predict the actions of others. This will include better knowledge about Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism not as institutions or philosophies but in their presence in narratives.

I would like you to notice that there are some fundamental differences in the status of romantic love in East Asia and the West and some less dramatic differences—but significant—among the three countries.

I would like you to gain more sophistication in interpretive method.

I would like you to encounter a country, at least one, about which you don't know much.

I would like you to hear the opinions of others and notice how diverse worldviews, values and interpretations can be.

I hope students can become more articulate in expressing their thoughts on “love” which requires better self-awareness of their own values as well as sensitivity on how others think differently. Dialogue is a key element of this class.

Our course theme is the interpretation of romantic narratives in East Asia (China, Korea, Japan), both premodern and modern. Here are our main topics under that theme:

The below is my basic list of areas of comparison in the treatment of core romantic values in narratives of China, Japan and Korea, selected by me because they offer particularly rich opportunities for comparison.

- Love as we read / view it in our East Asian narratives compared to the West. This is not the primary topic (we compare EA countries) but the reality is that all of our countries are making their own choices in terms of the place of Western values within their own culture and thus to compare East Asian countries as they are today is to include the question of modernity in various forms. We look at some contrastive issues between "East" and "West" to clarify our thinking:

- Sacred and non-sacred love, including the role of moral ambiguity in narrative. Love as the preeminent human value closest to divinity and associated with truth, goodness, permanence, transformative healing powers, empowerment, etc. vs love as first priority at a personal level but problem not at a society-wide level, weakening, fraught with trouble, etc.

- Passion vs the golden mean: Extreme states as indicative of truth (being overcome with desire means I have found my true love) vs. extreme states as dangerous (throwing one off balance, disrupting society, etc). The "golden mean" is important to Daoism, Confucianism and Buddhism, all, in one way or another; "passion" is a Western step towards truth (Plato), or full commitment (Jesus's sacrifice), etc. Passion is at the root of the pagan expression of love found in tango and flamenco dancing, too.

- "active agents exerting free-will vs. passive agents accepting fate": romance as measured by action (including sacrifice) or measured by the powerful embrace of fate — narrative positions based in part on assumptions of cosmic order and harmony (yin-yang, etc.) including gendered roles.

- Context as setting the direction of interpretation. One of the key assumptions of this course is that context has enormous influence on interpretation. In the ambiguous world of love ("Can I trust him?" "Does he love me?" "Why did she make that face just now?") context is often the only life-line towards an accurate interpretation of a situation. We study three countries. They are different. That means different contexts. We can tease out differences between countries by looking at how context is providing interpretive situations for us.

- Communication: This is key to understanding a culture's worldview and values. This broad term covers a wide variety of things:

- direct/indirect, blatant/subtle

- full, partial or little to no communication by choice or by circumstance

- ability or inability to communicate with one's partner (including Confucian hierarchies constraining the woman's ability to speak)

- honesty in message, deceit in message (although one might think that the idea romance is full honest disclosure between partners, our romantic narratives seem to suggest that there can be no romance separate from deception, an interesting point)

- vehicles of communication such as poems, letters, spoken words, eyes, actions meant to be taken as statements

- Confucian hierarchies: this can be various Confucian values in conflict with one another where the issue is which values should come first, or it could be explore tension between Confucian values where there is no obvious solution to the question of priority, or it could be issues of individual need versus societal requirements including modern formulations of this where contemporary values of the individual pursuit of pleasure and happiness challenges Confucian structures (this is listed above under a slightly different title as "active agents exerting free-will vs. passive agents accepting fate"). Derivative of these issues are power structures and their influence on romantic relationships, including woman's status which is generally limited in one way or another, a condition that might be accepted or challenged by the narrative in question. While we don't pursue it much, some students might want to take further the role of money in romance. I list it here because often, but not always, it is part of how power hierarchies are being marked by a narrative.

- Buddhist assertion that this world is illusory. Marking romantic feelings as fleeting or debilitating or unreliable, etc. Dreams, sometimes, but more usually "dreaminess" — narrative & cinematographic techniques that enhance a sense of illusion or other dream-like qualities.

- Metaphysics / psychology of the intimate bond: What brings lovers together, what binds them together, how is this narrated? Classic Chinese cosmological assertions of the five elements, Buddhist notions of karma, modern implied explanations of a chemical "love at first sight" as well as more traditional (and calculating to some degree) formulations of natural attraction — "women will hope to be selected by handsome, powerful men and men will naturally select beautiful, faithful women (caizi-jiaren narrative pattern)" and Confucian prescribed roles of husband-to-wife are all make an appearance in the materials we cover.

- “Layering”: the predisposition to conflate narrative characters, events that happen at different times, expectations, conflicting emotions and so on. We study this because, at heart, this is a challenge to Western notions of two individuals of free-will choosing one another in an act of love and commitment since it corrupts and confuses boundaries of personal identity. Includes the predisposition to narrate the experience of love as a dream state. Layering might relate to the notion of metaphysical correspondences (Chinese cosmology, Daoism) or cyclical notions of time (Chinese cosmology) or other achronic representations of time in narrative (past in the present, unstable time, memory overtaking reality, etc.) or illusion veiling reality (Buddhism). But layering might also be interpenetration (Daoism, Huayen Buddhism) of identities. In any event, boundaries and identities are made ambiguous. Related to this is an interpretive point: “Blending” is a term I sometimes use. It isn’t exactly a topic but it is phenomenon that is ever present as we try to sort out emotions, motives, expectations, and so on. By this I mean that narratives about “love” tend to be non-specific and evoke a variety of issues at once in ways that, if separated into discrete parts, do not become easier to interpret; rather their original meaning is lost—we can focus on a area but if we dissect it only serves to obscure.

- In narrative, linear and non-linear timelines and the status of memory.

- Deception’s role in both facilitating and subverting “love” as well as its general acceptance or rejection that the narrative seems to suggest. In some cases, betrayal / loyalty or faithfulness are related to this; in other cases, not.

- “Love” as not particularly the main topic but what is used to create a heightened environment for considering other topics such as loneliness, vengeance, and so on.

COURSE BOUNDARIES

We study heterosexual love—not for moral reasons but because we are studying social norms and if we include homosexual love, we need to include the study of the changing social norms in the three countries, making our course content overflow.

We study core, traditional values, not just any value. “Traditional” does not equal “conservative” and does not equal “your parents' values”. For the purposes of this class, by “traditional” I mean values (and social practices derived from them) of a country that were widely held over significantly long periods of time before the modernization for that country. By “core values” I mean values that most individuals, at least in public discourse and action, would be uncomfortable not upholding—for example, monogamy, prohibition against incest, etc.

Countries: Our countries are China, Korea and Japan. Korea includes the full peninsula. China includes Taiwan. See "Terms" for a more precise statement.

Anything in bad taste is out-of-bounds and any film your partner(s) is not comfortable with is out-of-bounds.

COURSE ASSUMPTIONS

Context plays a massive role in interpretation. When working cross-culturally we are at considerable risk at providing the wrong context. It is possible to get better at noticing this error and it is possible, though difficult, to gain subtle, working understandings of unfamiliar contexts.

While it is not always the case, we generally treat the experience of love as a gendered one, and not the same for each gender.

Love as we will study it can take different forms. These differences might be easy or hard to notice, they might be small or enormous.

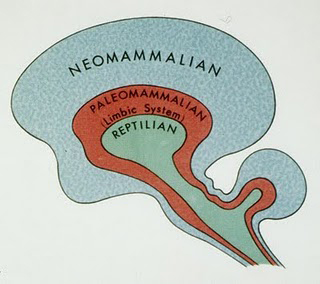

We work from a psychological model where reptilian, paleomammalian and neomammalian layers of the brain all contribute to the experience of love, but we focus on cognitive activities in the cerebral cortex while acknowledging that they take place in dialogue with the emotional context generated by the limbic system (especially the amygdala and hippocampus).

Further, I work from a model that it is possible for the brain to embrace multiple personalities to a minor or major degree, that therefore one’s self may not necessarily be a single unified entity but rather a fragmented one and that self-deception plays a role in this process. I extend this psychological model to cultures more broadly: cultures (even individual narratives) are multifaceted, contradictory (sometimes stunningly), and in places lack awareness of or interest in these contradictions. Your analytic conclusions, therefore, can include aspects of your object of analysis which are disjunctive or otherwise irrationally contradictory in terms of competing values and worldviews.

Our object of study, love, is a mixture, a blend, of various emotions and calculations and it is not possible to sort these into discrete entities for the convenience of study one by one. For example, “jealousy” in some situations cannot be discussed without acknowledging the affect of powerlessness. Or, as another example, in some cases erotic desire cannot be meaningfully studied without discussing the individual’s political power or financial strength. That a country’s official philosophy is Confucianism is relevant to the private experience of love—there is no firewall between the two. “Blending” includes, by the way, Freud’s concept of over-determination, where there are more psychological causes for a relationship than are necessary to explain an action. We solve this analytic problem by focussing on an aspect of love while acknowledging the limits of our analysis rather than creating a false analytic environment that asserts distance from these other relevant factors.

While all three countries that we consider (China, Korea and Japan) are modernized (and so fully involved in “modern love”), they, like the United States, continue to explore, define, and experience love within a context of traditional ideas in many cases and this presence might be various obvious or almost invisible when in action.

We are social creatures and experience love via a relationship (real, imagined, expected, past, whatever). We study relationships in this class.

Narratives are part of the very structure of our psyche and essential for us to understand experiences. Narratives are discursive and profoundly involved in language. Love as a full experience resides within narrative and the languages of narrative and so a full understanding of love in our countries would require careful attention to the languages of those countries. However, the regional bottom line position of this class requires that English is our common language and all is based on that, whether it be English translations of premodern material or subtitles. However, we should never forget that our conclusions must be provisional and would be substantially better if grounded in the language of the country in question.

COURSE RULES

Basic rules

On time arrival is expected. If you are late, go quietly to your seat.

No multitasking in class—laptops are OK but be very careful that they are used only for note-taking. There is NO NEED to look up any information during class. I watch participation very keenly. I assume that if I notice you multitasking that you are frequently, if not constantly, multitasking. It has a serious impact on your grade (course participation grades in the "C" to "F" range, even if just one time).

In all class activities, stay within the themes and goals of the course. Ultimately your work is graded on whether it contributes to the course goals, not whether it is "good" by other measurements.

Honesty. Much of this class works on the honors system.

Full cooperation with your essay partner(s) in all matters having to do with the project but in particular with setting up and keeping appointed meeting times.

Tolerance:

- I request demeanor that creates an atmosphere where everyone is comfortable about stating his or her opinion. This includes no signs that suggest you know a language better than another (for example, snickering at subtitles), or suggestions that certain opinions are naïve, unethical or whatever. It also includes no signs or suggestions that one country is “odd” or one country is more reasonable, etc.

- I ask that you try to understand other points of view through listening to others instead of just waiting to state your own point of view. This class is built on dialogue, not monologues.

- This class is not the place to promote a certain religious position on love. We study love as others think of it, not argue for positions.

All comments are in good taste. We must talk explicitly about sex in this class. Please contact me if you are uncomfortable for any reason, either lecture content or issues in the essay writing process. All film screenings are of “R” rated material. If I plan to screen something that is “NC”-rated, you will know ahead of time and that screening will be optional.

“Average Joe” rule: Your analysis should go farther than what an average Joe or Josephine walking around on campus would be able to say if asked the same question. In other words, analysis is not the stating of the most obvious or most defensible but looks farther into the issue to bring to light things another might not notice without considerable effort.

“Always about love” rule: Because it is enormously redundant to mention it every time, please remember that always we are talking about issues related to love not other things. If I say “What is the main point of this passage?” I mean “In terms of the romantic content (or other love-related content), what is the main point?” We discuss government, money, lying and so forth, all types of things, but everything is in this context of love. So not, “Is lying right or wrong?” but rather “What is the role of lies in a romantic relationship?” Students are always getting off-track on this point. Remember: always about love.

“High-low love” ("cognitive-chemical/visceral love") rule: As stated under assumptions, we are studying cultural contexts and how they establish expectations, actions and interpretations related to love. That humans (and animals) all over the world are attracted to each other is news to no one. We avoid these biological drives and focus on more complex and subtle cognitive / cultural issues, the “high” (a simple tag, not all that accurate perhaps). [Written 2/27/2012, hopefully some day I can get back and rewrite the full paragraph above] NOTE: Some students have misunderstood the high-low rubric as good morals / bad morals. What I have in mind is more along the lines of "above the waist" / "below the waist". That is, "what society signals love is" "what you are thinking" vs. "chemically-determined responses" "primary emotions (non-cognitive, generally non-discursive)". I presented this as "low" love being what is experienced / generated at the "core" of the brain ("reptilian" brain) as opposed to what is generated in the cognitive layers of the brain (cortex, "neo-mammalian" brain) with, in between and actively negotiating between the two, the limbic system and its multitude of nuanced emotions. So, we consider cognitive positions, definitely, and look into emotions that seem to be reaction to cognitive processes (i.e., "He is trying to steal her from me ... jealousy!") but we don't consider basic sexual drives, basic social drives to bond, basic existential needs to have an identity via the loving recognition of another, or, if Freud is correct, basic death impulses—anything that seems like it will, by nature of chemistry, brain physiology and such, be fairly similar across country / cultural / linguistic borders. Our goal is noting cultural differences, not unearthing the experience of love at its core, interesting though that might be.

“Equal interest” rule: Equal interest and effort made towards at least two of the three countries that are out topic.

Rules regarding films:

No drinking, eating or talking during films.

Whenever sitting for a film avoid blocking the view of subtitles for other students.

English subtitles are the official language we use for interpretation of the films. All films screened in this class and all films used by students for this class must have competent English subtitles.

Films used by students must be of good quality, complete in the edition, and equally accessible by both teammates.

Rules regulating interpretation that need to be kept in mind:

Special terminology request: Please use "values" to mean things that proscribe, the things that a society, for whatever reason, asks or expects of us as in sentences that can be written: "One should keep one's promise." Avoid using "values" to mean things that we believe (or are supposed to believe) such as the impermanence of all things in the universe. (It is confusing in general, and definitely in terms of this class, to say "One should be impermanent.") Also avoid using "values" in the sense of "things that are highly valued" when I ask "What are the values of this culture?" I am asking about social norms, not what is prized. This is an important distinction because we look at two primary areas that shape our romantic narratives: context (what a religion or whatever says of how the world works and so how we should understand any specific item in it) and social pressures (values, what one should do). I usually only ask about one of these at a time since mixing them together confuses the issue. This is one of the basic interpretive rules: try not to mix together, try to focus on specifics unless the result is more rather than less confusion / informative analysis.

Characters in narratives are not real people. They don’t have a body or a functioning mind and your analysis cannot be based on treating them as real people. They are partial representations of many things, including the author’s negotiation of his or her views of love, those of his or her audience, and the internal demands of the narrative.

A film made in 2003 but set in Tang China is a NOT a premodern film, nor does it operate under premodern values. Remember that the setting inside an artistic work and the context of the composition of an artistic work are different cultural contexts.

No broad generalizations. (Logic, insufficient data:) Cannot conclude a value of a country based on a single film. (Diversity, countries are made up of subgroups and individuals can carry more than one set of values around with them, using different values for different contexts, and values within literature do not directly equal values in actual practice:) Cannot assume that a value is equally accepted by all members of a country. And, in terms of your own descriptive language, be as precise as possible. Avoid "love" and say "loyalty" when that is what you really mean. Say "envy" not "jealousy" when that is what you really mean, and so on. (Mark Twain: "The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.")

Is it love? Many stories about “love”, upon close inspection, are better described as about insecurity, or loneliness, or loss, or betrayal, or loyalty, or sexual attraction. Very often, the more closely you ask the question “What, exactly, is love in this narrative?” the more slippery the notion of love becomes. There is no single location where it resides; it is in relationships of people and ideas. “Love” is, fortunately, a loose and flexible term. (And this is true of terms related to love in our target languages as well.)

THE CHARIOT ALLEGORY FROM PLATO'S PHAEDRA

"When the appointed hour comes, they make as if they had forgotten, and he reminds them, fighting and neighing and dragging them on, until at length he, on the same thoughts intent, forces them to draw near again. And when they are near he stoops his head and puts up his tail, and takes the bit in his teeth. [254e] and pulls shamelessly. Then the charioteer is worse off than ever; he falls back like a racer at the barrier, and with a still more violent wrench drags the bit out of the teeth of the wild steed and covers his abusive tongue and -- jaws with blood, and forces his legs and haunches to the ground and punishes him sorely. And when this has happened several times and the villain has ceased from his wanton way, he is tamed and humbled, and follows the will of the charioteer, and when he sees the beautiful one he is ready to die of fear. And from that time forward the soul of the lover follows the beloved in modesty and holy fear." (Plato's Chariot Allegory)

TWO WESTERN SCHEMA OF TYPES OF LOVE

ARISTOTLE'S FOUR TYPES OF LOVE

Aristotle's four types of love and my thoughts on them, based in part on Isaac Singer's The Nature of Love:

eros (attraction)

Sexual attraction. In Plato's schema this is the lowest form of desire though desire in and of itself is not wrong. Men seek the good and that seeking is marked by desire. Desire, though the growth of character, is redirected from sexual passion to a passion for truth (philosophy). In Plato's sex between a man and woman was not quite at the level of intimate relations between educated men. (See below.) Eros is placed front and center by Freud. And it remains highly valued now. However, it was somewhat marginal in Plato's world … and this is closer to East Asian premodern views of love.

philia (friendship)

Brotherly love. Friendship. Intimate relationship between man. Despite our common phrase "Platonic love" there was no such thing between the sexes. There were brotherhoods. However, that there can be non-sexual intimate relationships, truly warm ones, is fully endorsed by us.

agape (love thy neighbor as thyself)

Compassion, that is, gifting love to another. This becomes the model of Christian love and is still taken, I think, as the highest expression of "true" love: sacrificing for another. However, devoting oneself to another blends with this, see below.

nomos (law, submission)

This is not fundamentally a romantic value in Plato's world. It is about law and society. However, I find it interesting that there can be a crossover between submission to the law, to authority, and romantic submission / domination, including devotion. "True love" in the West is probably a blend of willingness to sacrifice oneself for another and commitment/devotion to another.

(R. J.) Sternberg's Triangular Love Theory

Here's a good academic source on this theory. It is not clear to me who the author is (it looks like galley proofs that we get as author's at the prepublication stage, for proofreading) but it is a very good representation of Sternberg and has a good bibliography as well: http://www.sagepub.com/upm-data/3222_ReganChapter1_Final.pdf Of course you can just Web search the term and you will get images and text related to this widely discussed schema.

Daoism

Main points from the suggested reading titled "Naive Dialecticism and the Tao of Chinese Thought" in Indigenous and Cultural Psychology

(By the way, I think the "dialecticism" in the title is being used by the authors to mean "reasoning and judgment—used towards solving problems of meaning [as in, "what is the situation I find myself in?"] and choosing appropriate actions/responses.)

The Chinese are socially Confucians but mentally Daoists.

Basic Daoist concepts:

- Non-duality

- Comment: Since all energy, all things, are derived from an original chaos, all things are links, even forces that seem to be opposing one another. Therefore, one cannot eliminate the opposing force, only strike a certain balance with it.

- Two poles (yin-yang, 阴阳・陰陽)

- Comment: quoting Wiki: Yin and Yang which is quoting Osgood, Charles E. "From Yang and Yin to and or but." Language 49.2 (1973)—

Yin is characterized as slow, soft, yielding, diffuse, cold, wet, and passive; and is associated with water, earth, the moon, femininity and nighttime.

Yang, by contrast, is fast, hard, solid, focused, hot, dry, and aggressive; and is associated with fire, sky, the sun, masculinity and daytime.

- Comment: quoting Wiki: Yin and Yang which is quoting Osgood, Charles E. "From Yang and Yin to and or but." Language 49.2 (1973)—

- A full circle of perpetual change

- Three treasures (ching/qing, chi/qi, shen/shen)

- Five elements (wu hsing/wu xing, 五行: wood 木, fire 火, earth 土, metal 金, water 水)

- Non-action (wu wei 无为・無為)

Major principles:

- Principle of Change

- Principle of Contradiction [complexity]

- Principle of Relationship / Holism [interpenetration, interrelatedness]

Further comments

The scholars of "Naive Dialecticism" have connected very well basic Daoist principles with our course question "What might be the context that helps explain a Chinese romantic narrative?" I would like to add, however (these will be discussed in class):

- Layering & correspondences

- Blending

- Codification of gender differences

- Comment: I would like to add a side note: Daoism shows a preference, in my opinion, towards yin when it comes to action; that is, to yield or to be flexible is a stronger position than to insist and be inflexible. At a crude level this appears to be an admonition to take a passive rather than active position. But this is thinking in "Western" terms with Western conceptual predilections. I would suggest that "yin", as a nuance in Chinese (or Japanese), sounds much more likely to be tied to a successful outcome than "passive" in English does — so we should proceed wtih care.)

SOME THOUGHTS ON BASIC BUDDHIST PRINCIPLES

Opening comment

Love that has a strong carnal element manifesting as the desire for someone, extreme attachment to someone, issues of possession of another and possessive jealousy and so on are not celebrated in the Buddhist tradition. Unlike Greek philosophy that sees passion and desire as a movement towards truth, even if misguided, passion, in Buddhism, is decentering and desire is based on an ignorant view of the world. Romantic love still has power and mystery, and still is compelling, but it almost certainly will be clothed in trouble and suffering. The Buddhist teaching that this is a world of illusion leads quickly to metaphors that use dreams and dreamstates to describe the experience of love. This makes love not powerful and healing as a positive presence but rather quick to dissipate, unreliable and ultimately void. ***Please select an accurate term when you are talking about this phenomenon: dream, dreamstate, dreaminess, and so on. Dreamlike is not the same as dreaminess, for example.

Main point

Buddhism offers a penetrating critique of reality and desire in ways that subvert optimistic, transcendent romantic narratives but can deepen romantic narratives that turn on anxiety, insecurity, loneliness, lack of trust and so on.

Details

I argue that the type of "love" affirmed within classic Buddhist ideology of China (and Korea / Japan) and on which it bases its ethics is benevolence and is represented by the figure of the bodhisattva. Romantic love, our topic, is not embraced although selfless sacrifice for another can be seen as supported by its positions. Family is not particularly important in strict Buddhist ideology, although it has been embraced over the centuries in Buddhist practice.

Generally speaking "being in love" is viewed as one of the many ignorant states of humans lost in an illusory world that is characterized by suffering as a result of, or response to, change (dukkha). (The Four Noble Truths: ) This emphasis on ignorance manifests itself in stories of love as romantic caution, narratives of the unreliability of romance, states of despair, distinct lack of exuberance, emphasis on tears, and so on.

Desire itself lacks the positive valence given by Greek philosophy where the desire for the beautiful leads eventually to the desire for truth. In this system, desire has karmic results that perpetuate states of suffering. Ironically, the concept of karma (cause and effect that links one state to the next, often explicitly stated) and the related assertion of the cosmic interpenetration of all things (rarely explicitly stated but seems to be atmospherically present in some depictions of intimacy) can serve to underpin/explain/suggest notions of fate, inexplicable attraction, sense of intimacy and bondedness to one's love. While notions of destiny and fate are familiar to Daoist metaphysics, Buddhism has had a strong role in enhancing "fate" as a way of viewing the future, and understanding one's situation, and guiding one's actions. Karma has been used to explain human bonds (love at first sight, a sense that two people already know each other, a promise to meet again in the next life).

Similar to the interest in balance that we see in Daoism and order that we see in Confucianism, Buddhism avoids extreme states and teaches the value of poised, balanced, calm contemplation (the Middle Way, the Golden Mean). It is only through practicing contemplation that one can find one's way out of suffering. Extreme states and extreme actions simply blind one to the truth and further entangle one in karma. Perhaps it is only through extreme sacrifice that one is allowed to show one's passion for someone?

For example, "to be passionate about something" is a positive phrase in English, a concept foreign to Buddhism. Here are some excerpts from the Oxford English Dictionary, tracking the development of the work "passion" (notice the religious origins of the word, and the sacred pairing of pain with good acts): sufferings of Jesus (end of the 10th cent.), narrative of the sufferings of Jesus (1119), physical suffering (beginning of the 12th cent.), strong emotion, love (beginning of the 13th cent.), fact of being acted upon (1370), enthusiasm, zeal (beginning of the 16th cent.), etc.

Thus, romantic love happens either outside the boundaries (non-cognizant) of Buddhist truths or in recognition that romantic love must be closely tied to suffering, and will be transient in nature. This makes it difficult to find soaring, transcendent romantic love within the shadow cast by Buddhist influences, unless it is either transgressive (which is not usually an exuberant state for premodern individuals who ultimately accept the normative value of their society) or grounded in, for example, a celebration of sexuality or such arising not out of Buddhist practices but rather other indigenous beliefs. I might, however, mention the important exception of tantric Buddhism although this has not provided the dominant ways of thinking about love in premodern, Buddhist, general, cultural environments.

Given that Buddhism posits this world we experience as a world of illusion,

... and given the visceral affective quality of being in love as disorienting and being transported into a "special" world,

...

and given that Buddhism uses the metaphor of dreams to depict this world (and this was true of early Daoism to some extent and very much true of the Daoist-Buddhist merged thinking that was common in China as the two traditions developed and interacted),

... it is not at all surprising that "dreams" or "dreaminess" in a multitude of ways appear in narratives of love.

Managing Buddhist concepts

Managing Buddhist concepts in this class is a bit tricky. Clearly in premodern times Buddhism functions primarily as a subversive element in romantic narrative, suggesting that being in love is a state of ignorance (since we live in a world of illusion and romantic love is very much of that world), or weakening / debilitating (since desire, even desire for stability and security causes suffering) in some way, or unreliable/fleeting (since everything changes). However, in modern times we are confronted with narratives that might include existential angst, or simple ennui, or urban malaise, or a whole host of other negative values which subvert or problematize romantic feelings. It is very tempting to say these are Buddhist narratives since it seems to be the answer I might want. But this is not the case. We are looking at what of traditional values remains, or not, in modern romantic narratives. Make your own decision on how "Buddhist" a narrative that seems uncertain and painful really is. This is important. Further, not all sadness in premodern texts is "Buddhist" sadness. Please be careful not to quickly assert that Buddhist concepts are what are behind the unhappy feelings of any given situation. Further, try to understand the distance between classical Buddhist teachings and the more "lay" or generic or popular understanding of Buddhist teachings as they appear in narratives.

SOME THOUGHTS ON BASIC CONFUCIAN PRINCIPLES

*There is probably a sidebar tab that leads to a page where many of the below terms are pronounced, in case they are new to you *Just for your review: The "five relationships" of Confucianism are ruler/ruled. father/son, husband/wife, elder/younger. friend/friend. The "three bonds" of Confucianism are ruler over ruled, rather over son, husband over wife or a woman submits to her father, husband and son. Confucianism pervades all three of our East Asian cultures. The larger points are consistent but the finer points have always been debated. Confucianism is relevant to use both in what it has to say specifically about love between husband and wife (and its essential silence on love between lovers) but also the type of societies it generates which are the context for our love narratives (such as the near encoding of the inferiority of women into the system as it is actually practiced). Since we operate in an English environment, we must, unfortunately, deal with messy translations of basic terms. "Loyalty" in particular might be zhong 忠 or xin 信, and xin might, inaccurately, be translated as devotion rather than faithfulness, etc., etc. Below are my thoughts on some of these terms, written with our course themes in mind. They are not ordered in any particular way, and it is not a complete list, but it is a good start, I think. Please remember that as soon as we start to work within the English linguist sphere, we are invoking Western principles that color these terms in a certain direction. Also, the over-arching Confucian virtues of moderation, prominent place of family relations, value of education (and life goals in general), high regard for morality are very relevant to our class as well as some of the "in-practice" effects of insistence on conformity, acceptance of authoritarian rule, hierarchy (inequality) between individuals, society over individuals, dominance of men over women, and so forth.

human-ness (ren, jen, 仁) benevolence, love of humanity, deep understanding of human relationships — this is a very important category to us which includes sympathy, empathy, benevolence, and so on

propriety (li, 礼) upholding social order, especially by honoring customs, rituals, social norm; knowing one's place and acting accordingly (inferior respects superior, superior cares for inferior)

loyalty (zhong, chung, 忠) as commitment to the benefit of another, acting to enhance another (person, institution, ideal) NOTE: Loyalty not as relevant to us because it concerns actions that support through actions (with verbal advice counting as actions) a superior (different than simply being in a state of devotion to someone). Since the wife is not superior the man is faithful in his promises to his wife (and benevolent with regard to her needs) but doesn't engage much in actions that would enhance her power or warn her away from harm. And, considering things the other way around, in a Confucian context a woman is not very dynamic in actions; she is in a state of promise and secondary support to her man. There are exceptions, though.

faithfulness (xin, hsin, 信) as in keeping one's word (so, not "devotion"), trustworthiness, keeping one's word, fulfilling one's promise NOTE: Faithfulness is very relevant to our class and we can understand issues of fidelity / infidelity, betrayal, trust, trust-worthiness, deception (including seduction) as related to faithfulness in one way or another

*To help distinguish zhong and xin, note the Chinese characters: xin is more about word-based contractual matters and behaving in ways that one's words are reliable; zhong is more about attentiveness to principles, being in the center of a principled view. The primary problem is that we widely use, in English, the word "loyalty" to describe someone who is devoted, reliable and so on, within a romantic relationship. When we translate zhong as "loyalty" we need to keep in mind the more specific, action-oriented, loyalty of zhong and use "faithfulness" (xin) when discussing devotion even if, as an English turn of phrase, it seems a bit outdated.

duty (yi, 義) doing what is right

filial piety (xiao, hsiao, 孝) love within the family, recognition of one's debt to one's parents

IMPORTANT NOTE ON "LOYALTY" FOR THIS CLASS, PLEASE READ!

Students sometimes use "loyalty" when interpreting love relationships. Or, more precisely, use the word "loyal" in sentences like this: "She remained loyal to him." This means, I believe, that she maintained her monogamous relationship with him in terms of sexual intercourse and perhaps also in terms of private thoughts of monogamous commitment.

This is a misuse of the word "loyal" for this class. Please do not use it in this way. It is just fine in normal speech and even in most academic discourse; it just happens to be a poor word choice for us because of our need to separate clearly modern and premodern values.

The problem is that such a use of "loyal" is grounded in a modern construct and so confuses the issue when considering premodern values having to do with Confucianism. In modern times a man and a woman more or less choose to be "loyal", that is, to be monogamous even in the face of temptation. It is a natural and informative use of the English word "loyal".

Unfortunately, it mixes up, in traditional Confucian values, xin (信, our class English equivalent: "faithfulness" "keeping promises" etc.), yi (義, our class English equivalent: "duty"), and li (礼, our class English equivalent: "propriety" "upholding social norms" "social norms" "social order" "keeping up appearances", etc.) and has very little to do with zhong (忠, our class English equivalent: "loyal behavior" "loyalty" etc.)

If you want to talk about a modern couple's action of remaining monogamous or something along those lines, please use the less frequent English word "fidelity" to replace "loyalty" or consider "devotion". However, in the case of "devotion" use it in its strict sense. In other words, please don't use "devotion" to mean "He's really devoted to me" since that isn't very informative: it is just another generic way of saying "He likes me a lot" or "He loves me a lot". Use "devotion" when you mean, "he places me before himself" "he puts me on a pedestal" "he idealizes me". This ends the confusion with zhong (忠, loyalty).

If you want to talk about a premodern couple's action of remaining monogamous, please remember that it is not necessarily about a romantic free-will choice to stay with one person that you love, to not sleep with others. It might be simply a strong sense the you must uphold social norms (li, 礼), or fulfill your duty as a wife or husband (yi, 義), or keep your promise of commitment (xin, 信). It might also be a marker for the presence of intense passions when no one else interests the lover(s). This is NOT a Confucian value ("one should ...") but it IS part of the East Asian world of romance: qing (情, Chinese), nasake (情, Japanese), jeong (情, Korean). Further, strong bonds might also be understood in terms of karma (sense of an invisible bound sense to another, fate).

If the premodern or modern couple's intimate closeness seems to include wanting to take care of someone out of a Strong sense of benevolence or sympathy, then ren (仁, our English equivalent: "human-ness") is part of the mix.

On the other hand, if the premodern or modern couple's intimate closeness seems to include wanting to be taken care of by someone seems to be an important characteristic, then amae (甘え, if the context is Japanese) or something similar to this (if the context is Chinese or Korean) is part of the mix.

Finally, don't forget that desire is usually the bottom line in all of these stories. The trick is desire for what? Desire is NOT in any of the above terms, strictly speaking, but is of course a premodern and modern characteristic. We usually do not discuss desire, we just assume it, because of the "high-low" rule. Sometimes, though, desire is meaningfully bound to cultural norms in some way such as high valuation placed on social status and so forth. (The irogonomi man is of high social status; the talented scholar is highly educated. Either of these can cause desire.)

DAOISM – CONFUCIANISM – BUDDHISM – AND BLENDING IN MODERN CINEMA

Modern films about romance don't usually take up as a specific theme an exploration of Daoism, Confucianism or Buddhism. They tell stories of cautious or naive hope, necessary or ill-intentioned betrayal, romantic joy, despair of loss, difficult choices, devotion, sacrifice and so on. Nevertheless, all stories work within a constructed world that includes a worldview of some sort and values (sometimes thought over carefully, sometimes only casually present). These worldviews and values come from somewhere. The question we ask in this class is whether premodern views are part of the mix. This never means "that is the Buddhism we encountered in The Tale of Genji. Buddhism, as a presence in modern societies, is a living object that has evolved and intermixed with many other ways of thinking. If a movie seems to focus on a fear that a romantic relationship is unreliable there are, no doubt, multiple reasons for this point of view including, probably, a modern acknowledgment (if not celebration) of the individualism that is so widely embraced today (individuals are likely to do what is right for them, not for others or their country). Even so, it is possible that a film can comfortably (in terms of audience reception) lean heavily on unreliability because, for centuries, Buddhism has argued for that point. When we are trying to understand the film, we are not trying to argue for an "either or" approach (it is a modern value that is causing the angst? is it the historic pressure of Buddhism?). I have suggested in this course that "blending" prevents making a choice on this point and leads to false analysis if such a choice is made. So, we are in the business of understanding narrative nuance by keeping in mind Daoism, Confucianism and Buddhism in their basic premodern interations to help sort through then many points of view involved in film-making / story-telling. If you were to tell a certain director "That's a Buddhist perspective you use in such-and-such a film" s/he would probably laugh, or contradict your claim. That doesn't make it incorrect. Generally speaking, we work instinctively within or worldviews and values. We don't think "Right now I'm being individualistic." If considering the Daoist element of a film seems to enrich its interpretation, and seems at some level credible, then the analysis, at least in terms of this class, would be seen as successful. "Blending" allows us to explore those "flavors" of a worldview or value without making unrealistic claims that substitute modern angst for a Buddhist view or "life is suffering" and so on. We allow the modern perspective; we explore within it possible nuances that have older roots than the 20th century. I do believe in history; I do believe not everything under the sun today was born just yesterday; I do believe that our understanding is more accurate, and more subtle, when we take history, the flow of culture, seriously.