Read this: The below is in three main parts: things related to style, spelling and grammar that get graded when you submit your essay (I), general rules about documentation (II-A) and a list of examples of how to cite things (II-B). This last part might seem long and detailed but that is really just me trying to imagine various situations you would want answers to so use it as a quick reference. It is not meant to send the message that I am super picky about citation details. Basic MLA is fine (but worse than that is not OK). BUT, Part II is important and the last sections having to do with footnotes is where students can score low and/or sometimes be judged by me as having been academically dishonest. We have several non-standard rules for footnotes and if you do not follow them you will not receive a good score. If you simply submit a paper in the way you are used to making footnotes you will not have followed these specific directions. Then, in terms of academic dishonest, my boundaries for fair and accurate use of source material are specific, spelled-out on the Academics Honesty page, and very important to me. They are probably more narrow and strict in definition than you are used to working with. If you do not read the Academics Honesty page and the instructions on this page, you may well be given an "F", or worse, for academic dishonesty. Read with care and ask questions ahead of time, not when I make such a judgment (since I rarely alter the penalty even after we have talked and come to an understanding).

Basic clarity of expression. Please reread and rewrite your paper for clarity. However, it is important that the essay sounds like you. Please do not have a friend rewrite it for better English.

Academic diction. Your essay language should be semiformal or formal. You can use “I” but please avoid causal phrasing and never use contractions (write “do not” not “don’t”). Stay decent: use “urinate” not “piss” and so on. Sound smart: use “two men in particular advanced the ideas of the shin-kankakuha movement” not “two guys …” Avoid being chatty, clever, etc. Sound balanced and reasonable but not cold and disinterested.

Spelling. Spelling should be nearly perfect through all parts of the essay, including footnotes and all bibliography components. Spelling should be 100% accurate for all important terms, all names, and so forth. This is true, again, for all parts of the essay, including footnotes and the bibliography components.

Just about any type of romanization of Japanese words is OK, but be consistent. Macrons (the long mark over an "o" or "u" usually) are optional. All of these are acceptable romanization solutions: shinjū, shinjû, shinjuu, shinju. There are other systems, too, such as sinju.

I encourage students who can work with Chinese characters to include them in their paper but always include an English equivalent and/or a romanized version, in case the characters do not display correctly.

Punctuation. I am not strict about punctuation. If you give it a decent effort you should meet my common sense standards. The one on error that students frequently make that does bother me some: ignoring the difference between a dash and a hyphen. Hyphens show word breaks (hyphen, where “phen” is on the next line) and word combinations (pre-wash); dashes set off clauses (“He trembled — not that he wanted to — every time she offered to make his drink.”) Hyphens are created with a single key on the keyboard; dashes are often created with the combination shift-option-hyphen. Check your computer. You can also triple-hyphen to represent a dash: --- . (A double hyphen actually is a different type of dash, used in serial numbers: 108–219. It is longer than a hyphen and shorter than a dash. I don’t require this distinction.)

Treatment of titles. Please get this right! Academic readers want to know the nature of your source, and this is indicated, in part, by how you style it. Many students read more journalist prose (in newspaper, online) than academic prose. The New York Times, for example, uses quotation marks for books. Please note the distinction between language environments. We are working with academic language, with its own specific expectations.

Treatment of foreign terms. Foreign improper nouns (that is, not names of places and so on) that are not common should be italicized: chashitsu (not part of normal English usage) but sushi (part of normal English).

Note: It should be "Emperor Suzaku" not "Emperor Suzaku", "Heisei period" not "Heisei period" and so on.

Treatment of proper nouns. Proper nouns are place names, names of people and so on. Please be rock-solid accurate with these! Capitalize them, of course.

Treatment of individuals you mention or cite. There is no standard way for how scholars and such should be mentioned in an article. But I would like you to follow these three rules, all of which are mentioned to deliver essential information relevant to the reader in a clutter-free way:

1. Lean towards using the last name of someone only, unless there is reason to mention the full name (in other words, last name only would cause confusion because there are two different scholars with that name, etc). So:

NOT: Helen C. McCullough claims that ...

RATHER: McCullough claims that ...

2. On the first mention of an authority you are citing or in any way using information from, tag that name with a short phrase to let the reader know something about them. Too much is distracting, but a little information helps the reader interpret that person's words. So:

NOT: McCullough claims that ...

PREFERRED:

the gender studies scholar Schalow argues that ...

McCullough, a scholar of early Japanese literature, claims that ...

the premodern Japanese scholar McCullough claims that ...

WARNING: when the modifying phrase precedes the name make sure that it doesn't create a misunderstanding: "the Japanese scholar McCullough" isn't clear as to whether she is Japanese or she studies Japanese literature. Use common sense and when in doubt rephrase to avoid misunderstanding.

TRY TO AVOID:

Sometimes this method is just clunky. For example, if all of your scholars are Japanese lit folk, then "Japanese scholar A" and later "Japanese scholar B" and later "Japanese scholar C" just seems pointless. However, if you are mixing and matching, say comparing the analysis of a sociologist with that of a literary critic, it is helpful to know they are of considerably different backgrounds.

3. Do not mention the title of a cited article in the body of your essay unless there is a clear reason to do so (for example, you are using multiple articles or books by the same person, the book itself is so famous it should be mentioned, or knowing the title right then and there -- not later when looking at the footnote -- does bring clarity to what you are saying, etc.). So:

NOT: In “Vicissitudes in the Ordination of Japanese “Nuns” during the Eighth through the Tenth Centuries” by Paul Groner, he argues that “nuns ...

RATHER, simply: Groner argues that “nuns ... (the article and location will appear in the footnote)

BUT, when you want to emphasis the importance or status of the source:

De Rougement, in his famous mid-twentieth century work Love in the Western World, argued that ...

In Okada's controversial Figures or Resistance, he asserts ...

II-A. Overview of citation components, with specifics on what is required for this class

- Opening comment

- Documentation — ultra-basics

- Author stuff

- Title stuff

- Publication info

- Various things at the end of a cite

- Footnotes—general comments IMPORTANT!

- Footnotes—when to footnote IMPORTANT!

- Footnotes—accessibliy for graders IMPORTANT!

- Footnotes—Fair use IMPORTANT!

II-B. Examples of basic footnote and bibliography entries, with common situations in my classes

- Book, originally in print form but accessed online

- Book, in print form

- Article, originally in print form but accessed online

- Article, in print form

- Online publication never published in print form (not first something on paper)

- Source is a component of a larger work (anthology, etc.)

- Very common sources/situations for our class—JSTOR, but a review, not an article

- Very common sources/situations for our class—Source has multiple authors

- Very common sources/situations for our class—Source has editors and/or translators

- Very common sources/situations for our class—Which to list, author or translator?

- Very common sources/situations for our class—What to do when no one knows who the author is

Opening Comment. The information you as the author include to allow the reader to fully and accurately identify the material you used to complete your essay is called “documentation.” It appears either as a reference note within the essay or as an item on a bibliography list at the end of the essay.

Anything that has appeared as a reference note, in our case, must reappear as an item on the bibliography. However, not everything that is listed in the bibliography, in our case, must have been a footnote, since we make a bibliography titled "Works Consulted", not "Works Cited".

There are extensive comments on my academic honesty page about footnotes. You should read them with care. Errors in the areas discussed on those pages result in, at minimum, miserable grade results, and can quickly be seen by me as academic dishonesty that I will prosecute. I very much would like you to not get tripped up with any of those specifics. Please read the page.

Documentation ultra-basics, as I see it.

1) Documentation information is chunked (and presented in the following order):

author stuff | title stuff | publication info | a variety of things at the end

2) Footnotes and bibliography entries are different animals. They treat chunks and punctuation between chunks differently. The overall principle is that a footnote is considered a sentence while a bibliography entry is considered an ungrammatical item/object on a list. Two basic differences flow from this:

a) the author's name is treated normally in a footnote but switched to last-name-first in a bibliography for A-Z ordering reasons, and,

b) a footnote links its chunks like phrases in a sentence, while a biblio entry links chunks with periods. (Parts inside a chunk, if any, are not usually separated by periods, which represent a strong break, but rather something else, usually a comma.)

So,

Footnote Firstname Lastname , ( ) . Biblio entry Lastname, Firstname . . . . 3) Footnotes give full information the first time they appear, and shortened information every time after that.

Author stuff. Three frequent situations: multiple authors, authors that do something besides write the text of the source, and Japanese names.

1) Multiple authors:

For footnotes, everyone gets listed in normal order: Bob Doe, Annie Doe, and Dim Doe,

For the biblio entry, the first, and only the first, lists last name first: Doe, Bob, Annie Doe, and Dim Doe.2) Authors can be something besides an author, and we need to know. So (role — usual abbreviation):

editor — ed.

editors — eds.

translator — trans.

translators — trans.

compiler — comp.

compilers — comp.*Noodletools has an extensive list: http://www.noodletools.com/helpdesk/index.php?article=127&action=kb

Click here if the link is broken: MLA 7th ed. abbreviation list

And these are listed like this:

For footnotes: Helen C. McCullough, ed.,

For biblio entry: McCullough, Helen C., ed.*Please notice that one period can work double duty, it is not ed..

*Please also notice that a comma follows the name, before the role indicator.

3) Finally, it is better to treat Japanese names like Western names for our essay, though often in the real world there is an editorial comment at the beginning of a book or such that states that Japanese names will be presented in their traditional order. So, for us, in the case of Yukio Mishima, where Yukio is his first name and Mishima is his last, we do this:

For footnotes: Yukio Mishima,

For biblio entry: Mishima, Yukio.

Title stuff. This information comes in two basic types: just the source itself, like a book, or a unit of some sort inside a larger work (vessel, container), like an article in a journal, a chapter or essay in a book, a poem in an anthology, and so on. First I want to make a note about foreign titles, then make a couple of comments for times when the work is inside the container.

1) When you have used a book in a different language, we simply must know that, and, in the case of this class, I also require an English translation of the title in the bibliography. Place it in brackets after the title. It does not need to be italicized. So:

Komatsu Tomi, trans. Izumi Shikibu nikki [The Izumi Shikibu diary]. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1985.

2) Please read this biblio entry:

Sōgi, Shōhaku, and Sōchō. "Three Poets at Yuyama." Wind in the Pines: Classic Writings of the Way of Tea as a Buddhist Path. Comp. and ed. Dennis Hirota. Fremont, Calif.: Asian Humanities Press, 1995. 180–187. Print.

This is a poem inside a larger work. It has three authors. The larger work was complied and edited by Dennis Hirota. The poem appears on pages 180 through 187. Please notice:

a) that there is nothing between the work title and its larger source except the usual period (no "in" or "inside" for example),

b) that the role indicator for Hirota comes before his name (and has no extra "by" or such),

c) that Hirota's name is in normal order, and,

d) that the bibliography includes the range of pages where the work is located.

Here, by the way, is the same information as a footnote where you want to refer to the entire poem such as this comment in your essay: "The full translation of "Three Poets at Yuyama" has been translated, among others, by Hirota." (If you were referring to a specific spot, such as this quote, "The dew is so chill / it holds the moon's / light / altered." then the page number should just read 181, the exact location of the line):

Sōgi, Shōhaku, and Sōchō, "Three Poets at Yuyama," Wind in the Pines: Classic Writings of the Way of Tea as a Buddhist Path, comp. and ed. Dennis Hirota (Fremont, Calif.: Asian Humanities Press, 1995) 180–187.

2) When shortening the information for a second citation, use the source title, not the container title, so:

Sōgi, Shōhaku, and Sōchō, "Three Poets," 181.

not

Sōgi, Shōhaku, and Sōchō, Wind in the Pines, 181.

Publication info. Elsewhere in the document I discuss how to find this information. Here I simply want to identify a very common problem I see in student submissions.

For books, publication information is "place: publishing company, date" so:

Berkeley, Calif.: U of California P, 1988

Whereas for journals and other periodically published things, publication information is "volume number.issue number (date)" not the name of the publisher, so:

34.4 (1993) — old citations styles might list this as Vol. 34, No. 4 (Winter, 1993)

Various things at the end of a cite. What comes at the end of a citation is different between footnotes and bibliography entries. They have at least this in common though: both are finished with a period at the very end. And the basic difference is this: the footnote has only a page number or numbers that point exactly to the location in the source you are referring to, while the biblio entry, has a wide range of information about the source.

So, as a biblio entry:

Hillenbrand, Margaret. "Doppelgängers, Misogyny, and the San Francisco System: The Occupation Narratives of Oe Kenzaburo." Journal of Japanese Studies 33.2 (2007) 383–414. Web. (28 April 2010) PDF file.

Please note that all of the below information is given in the biblio entry to provide the reader a full picture of the nature of the source:

As a footnote, we have simply:

Margaret Hillenbrand, "Doppelgängers, Misogyny, and the San Francisco System: The Occupation Narratives of Oe Kenzaburo," Journal of Japanese Studies 33.2 (2007) 399. (or whatever page you are referring to for that footnote)

A small note: I am not particular whether it is (2007): 383–414 or (2007) 383–414, that is, with or without a colon. I've seen it both ways. I don't use it—not because of MLA style rules but rather from a Chicago style habit to keep things as clean and simple as possible. MLA probably actually requires it, but still ...

Footnotes—general rules for my classes

A reference note can appear at the end of an essay (or chapter, or entire book), and in that case is called an “Endnote”. It can appear only within the text itself, and it is called an “in-text citation” or "parenthetical documentation" or something similar. Or it can appear at the bottom of the page and is then called a “footnote”. We use footnotes, so, the note should appear at the bottom of the same page where the reference number is in the body of the essay. In-text citations are more common and generally more useful but aren't useful for the way student essays are graded for this class.

Footnote reference numbers begin with the number 1, then 2, and so on straight through to the end of the essay.

Footnotes should use the full citation the first time, then a shortened citation the next and all subsequent times.

A full citation means the publication data AND a page number(s).

If a quote (or a passage referenced but not quoted) stretches over more than one page be sure to include all pages, not just where the quote or passage ends:

187–190

If a quote (or a passage referenced but not quoted) stretched over more than one page but not continuously, that is, midway the topic shifted to something else then returned to the discussion, include all pages but like this:

187–188, 190

When a footnote is followed by another footnote that uses the same reference and page number, it is possible to use Ibid. However, this is not much easier on the eyes than just repeating the note:

Walsh, 21.

Walsh, 21.as opposed to:

Walsh, 21.

Ibid.

Footnotes—when to footnote in my classes. This is a very common question from students and it is a judgment call. Too many footnotes clutter the work, too few degrade the academic quality of the work. Here are common scenarios when I would like to see footnotes:

The idea (conclusion, analysis, speculation) or information was generated with some effort by the scholar and that scholar deserves credit for it. "Forty percent of individuals who use ivory chopsticks while less than 10 years old develop arthritis earlier than average." That claim would have been the work of someone, obviously not you, and that person needs to get credit for it. Not to do so is a serious error in citation, one that is punishable. It is plagiarism even if you just messed up and forgot to cite it. There is very little room for forgiveness.

The idea (conclusion, analysis, speculation) or information is such that it is likely the reader would like to know more. You point them there. Your paper is serving the function of enhancing scholarship by making resources accessible. "There have been many studies on young children using light sabers as chopsticks." Wow, I'd like to know more. You really should give us a link via a footnote that points us there.

The idea (conclusion, analysis, speculation) or information is counter-intuitive or for whatever other reason is likely to generate doubt in the reader's mind. "There is a much greater quantity of water on the moon that was believed to be true a year ago." This is a true statement; however, there are probably readers who wouldn't think so. You protect yourself by documenting it. On the other hand, "There is considerable racial diversity among students attending Cal" won't be questions by your readers. However, if you lived in a country that did not know much of the outside world and didn't have racial diversity, they might not believe you and you would need to cite this. See how it works? There are no definitive rules; there are lots of judgment calls to make.

Direct quotation AND paraphrasing of course absolutely must have documentation. Further, the quoting, whether direct or in paraphrasing, must be accurate, not modified to support your argument. Not doing so is also a serious type of plagiarism that can have the most severe of penalties.

Not every sentence needs a footnote. Good judgment can be used here. When a scholar is cited and there is other similar information mentioned in something of a prose flow that could link all the comments together, the reader is likely to conclude that the other pieces of data are from the same source. (Ideas are a bit trickier to make this conclusion. It is better in the case of including a scholar's ideas — conclusion, analysis or speculation — to cite, to be on the safe side.) However, if more than one scholar is being cited in a back-and-forth manner or, for example, if one scholar is cited at the beginning of a paragraph and a different one at the end and the middle data is not cited, then it is hard for the reader to make a decision on the source. Plagiarism intentional and unintentional very frequently happens when the data is cited but not the analysis, leaving the impression that the facts come from someone else but the conclusion is yours. Be very careful to avoid this type of readerly misunderstanding.

Finally, and this is a very serious problem, plagiarism occurs sometimes when you have forgotten that something wasn't your idea. It slipped into your head while reading, it interested you, time passes, and you begin to think you own the observation or conclusion. Good research reading (not jumping all over the place, such as what happens when reading a number of web pages at a time), good note taking (because if you write it down, even once, it is less likely for you to forget that you learned it from someone else, not from your own brain workings), and writing drafts from notes are ways of reducing the chance of this slippery problem. Remember that you have no defense: if you present an interesting idea as your own and it appears in a work you are likely to have seen (even if you didn't), no one will believe that by coincidence your idea matches what is written. Nearly everyone, including the courts, will conclude that you have forgotten, intentionally or by accident, that you read it somewhere first.

Footnotes—accessibility by graders. All your cited sources must be accessible to your graders, either in the form of a hyperlink that works properly, or if necessary a file(s) such as screen captures, scanned material, or such. We much prefer digital files that can accompany your Step 03 and, if necessary, Step 04. Please contact us if you would can find no solution to this and simply must submit a hard copy.

If the cited source passage cannot be viewed by us, it will not count as part of your essay, and I will also wonder why it is not there.

Foreign sources can only be used if they are web pages that translate into English in a reasonable way (check it with Google translate) or if you have contacted us about the source and received an OK for each specific instance. I have had problems in the past with academic dishonesty that involved non-English articles: the quote didn't exist, the quote existed but was on the book cover flap not in an academic article, the quote didn't say exactly what was claimed and the accurate version contradicted the essay's thesis, and so on.

Footnotes—Fair use. Quoting from my own academic honesty page:

Imagine the author of the source looking over your shoulder, watching you compose your essay. Will he or she accept readily how he or she is represented by you? If so, you are being both accurate and fair. If that individual is inclined to say things like “You’re quoting me out of context.” or “That’s not what I meant.” or “You are making me look stupid by dumbing down my idea.” or such, then you are probably taking too many liberties with how you are presenting the source ideas.

There is, however, quite a bit else involved. As already noted above, please read my academic honesty page.

Book, originally in print form but accessed online

This is a screen capture of a book found through a Google books search. It is not the book in full, it is at the level preview, but it does include the copyright page. (This was the second page of the scan, when I scrolled down from the cover page.) This information is, of course, identical to the information you would find in the print version of the book, since it is a scan of that. You can also access this information through the Book Overview page, which appears when you have started your search inside Google Books, not just generally.

Note that I have boxed in red part of the Library of Congress info. The subjects listed there are a limited list published by the Library of Congress and used to categorize every book that is published in English. Authors might be asked what subjects they would like listed but the editors make the final determination of what will be listed here.

Note that also in that box is the call number. Oskicat allows for a browsing method where you list this call number then can scroll up and down to see what books are supposed to be on the shelf next to that book. This is a little like going to the library and looking at a bookshelf. Downside: you cannot open the book to see if it is useful. Upside: you can learn of book titles that are not on the shelf because they are either checked out, lost, or missing.

As a first footnote, this source should be listed as (pretending that you are quoting from page 133):

Donald Keene, Dawn to the west: Japanese literature of the modern era (New York: Columbia UP, 1998) 133.

As a second and subsequent footnote, this source should be listed as (pretending that you are quoting from page 185):

Keene, Dawn, 185.

As a item on the bibliography, this should be listed as (notice that page numbers are NOT listed):

Keene, Donald. Dawn to the west: Japanese literature of the modern era. New York: Columbia UP, 1998. Web. 21 March 2010.

Here is an example of the same book but in this case the student used the library book or a copy otherwise owned or borrowed. The footnote citations look exactly as above. The bibliography information towards the end of the cite, however, is a little different.

Keene, Donald. Dawn to the west: Japanese literature of the modern era. New York: Columbia UP, 1998. Print.

Article, originally in print form but accessed online

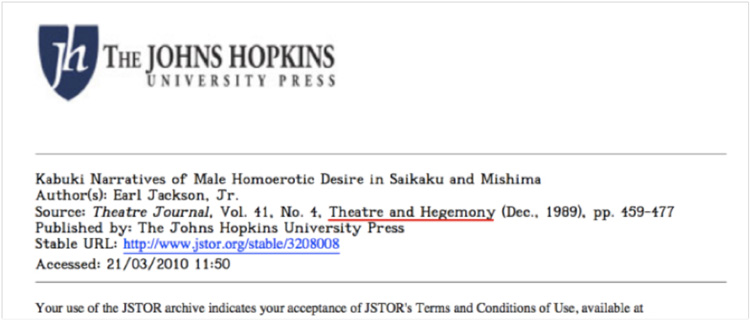

Below are two examples of where publication info can be found for a JSTOR article. The first is an information screen created by the JSTOR editors that you can see when onsite. The second is the information they place inside the PDF, before the article begins. Please remember that although they have listed the publisher of the journal, this is not including in a footnote or bibliography entry in the case of periodicals.

After accessing JSTOR and finding an article that you might be interested in, the initial screen for that article might look something like this. The bibliographic information is not quite complete on this screen. You need to click on the “PDF” button. Also, just for your information, the “Item Information” button might provides an abstract of the entire article. Very useful.

Onsite:

In the PDF:

Examples, using the "in the PDF" example, above:

As a first footnote, this source should be listed as (pretending that you are quoting from page 464):

Earl Jackson, Jr., “Kabuki Narratives of Homoerotic Desire in Saikaku and Mishima,” Theatre Journal 41.4 (1989) 464.

As a second and subsequent footnote, this source should be listed as (pretending that you are quoting from page 476):

Jackson, “Kabuki narratives,” 476.

As a item on the bibliography, this should be listed as (notice that the page numbers are those of the full article, not the pages referred to). Note how this includes the medium and when accessed. (In addition, I request the "stable URL" that is listed, as described elsewhere. Also note that you do not list the publisher in the case of journals even though that information is given on this page.) The month published has been dropped — (Dec., 1989) has become (1989) — because the issue number is included. One of the two needs to be there; for both to be there is seen as redundant and causing unnecessary clutter, though an argument can be made that it is more convenient to have both.

Jackson, Earl, Jr. “Kabuki Narratives of Homoerotic Desire in Saikaku and Mishima” Theatre Journal 41.4 (1989) 459–477. JSTOR. Web. 21 March 2010.

This bibliography entry identical to the above, except the information towards the end of the citation changes:

Jackson, Earl, Jr. “Kabuki Narratives of Homoerotic Desire in Saikaku and Mishima” Theatre Journal 41.4 (1989) 459–477. Print.

Online publication never published in print form (not first something on paper)

This is fairly unusual for our class. I have taken an example from the MLA stylebook. This is a bibliography entry:

Dionisio, Joao, and Antonio Cortijo Ocana, eds. Mais de pedras que de livros / More Rocks Than Books. Spec. issue of eHumanista 8 (2007): 1-263. Web. 5 June 2008.

Source is a component of a larger work

Common situations would be an article in a book that is a collection of scholarly essays or a poem/short story/excerpt in an anthology of literary works. Notice that in this case the page numbers of the full section of the book used are listed. Yamanouchi is the last name, by the way.

Oe, Kenzaburo. “Japan, the ambiguous, and myself.” Trans. Hisaki Yamanouchi. The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature. Vol. 2: From 1945 to the present. Eds. J. Thomas Rimer and Van C. Gessel. New York: Columbia UP, 2007. 805-813. Print.

Very common sources/situations for our class—JSTOR, but a review, not an article

Students sometimes don’t cite these reviews correctly because of the way JSTOR lists the information. The reason this is important is that the incorrect way simply doesn’t tell us much. Here’s a screen capture of a review on JSTOR, followed by a common way students incorrectly list this, then by the correct citation:

Incorrect:

Starrs, Roy. "Review: [untitled]." Journal of Japanese Studies 29.1 (2003): 230-34. JSTOR. Web. 31 Mar. 2010.

Should be:

Starrs, Roy. Rev. of Kawabata, le clair-obscure: Essai sur une écriture de l’ambiguïté by Cécile Sakai. Journal of Japanese Studies 29.1 (2003): 230-34. JSTOR. Web. 31 Mar. 2010.

Very common sources/situations for our class—Source has multiple authors

Multiple names are listed in the order they are listed on the title page. If the item is part of a bibliography and the name would be the first words of the citation, the first author name, and only his or hers, is listed in the last-name-first order. So:

In the first footnote:

J. Thomas Rimer and Van C. Gessel, eds. The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature …

In the second and subsequent footnotes of the same source:

Rimer and Gessel, Modern Japanese Literature, …

In the bibliography:

Rimer, J. Thomas, and Van C. Gessel, eds. The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature …

But (when the same names are not at the start of the cite):

Oe, Kenzaburo. “Japan, the ambiguous, and myself.” Trans. Hisaki Yamanouchi. The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature. Vol. 2: From 1945 to the present. Eds. J. Thomas Rimer and Van C. Gessel. …

Here both are in first-name-first order because they do not start the citation. The ONLY reason a name is ever reversed in documentation is for the purposes of A-Z listing order. (Footnotes don’t need this, for example.)

Very common sources/situations for our class—Source has editors and/or translators

When it is an editor or editors:

Last name, first name, ed. Title …

or

Last name, first name, and First name, Last name, eds. Title … (when there are multiple editors).

When it is a translator, list the author of the original first and include the translator after the title:

Oe, Kenzaburo. The Silent Cry. Trans. John Bester. …

Very common sources/situations for our class—Which to list, author or translator?

List the author not the translator at the beginning of the citation except in very unusual circumstances, such as when the translator is more important than the original author by some measure and/or is the specific subject of your analysis (example: “A Comparison of Translations of The Tale of Genji” might list by translator).

Very common sources/situations for our class—What to do when no one knows who the author is (of a premodern work, usually)

Unknown. Yoshitsune. Trans. Helen C. McCullough. …