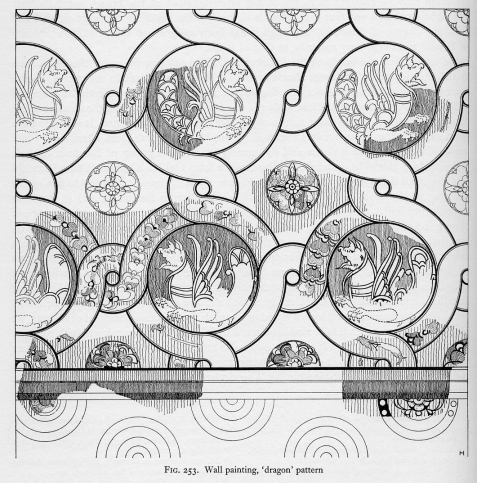

Figure 1. R.W. Hamilton, Khirbat Al Mafjar: An Arabian Mansion in the Jordan Valley, Oxford, 1959, fig. 253, copyright Oxford University Press.

An electronic publication ISBN 0-944940-18-8

Table of Contents

Among the fragments of wall painting found at Khirbat al-Mafjar were a group reconstructed to form a pattern of interlaced rings distorted to resemble guilloches surrounding disks filled with fantastic Sasanian animals usually called sīmurghs.1 The loops do not actually form guilloches but they appear to, so for convenience I call this pattern a guilloche net. The loops are filled with overlapping heart-shaped motifs. rosettes of four heart-shaped motifs arranged within borderless circles. Below a field of this pattern and separated from it by a horizontal border was a field of roundels bordered by “pearl” bands.

Figure 1. R.W. Hamilton, Khirbat Al Mafjar: An Arabian Mansion in the Jordan Valley, Oxford, 1959, fig. 253, copyright Oxford University Press. |

These fragments were excavated by Dmitri Baramki and published by him and, later, Robert Hamilton (in a contribution by Oleg Grabar). They have been revisited recently by Tawfig Da'adli, with the benefit of additional material recorded in watercolors painted at the time of Baramki's excavations.2

They came from the second floor of the northern half of the east wing of the palace, and were found in the debris of the ground floor, which had no wall painting itself.3

The guilloche net wall painting was discussed by Grabar under the heading “The ‘dragon’ motif”, along with three other patterns of which fragments were found in the same area (the “diamond” pattern, which is a lattice of rosettes alternating with fantastic flowers; the “rosette motif”, and the “rinceau motif”).4 Grabar did not identify all of the colors used, nor did he provide dimensions. Da'adli's article reproduces the watercolors in color, but they are clearly faded.

Grabar compared the guilloche net painting to Persian and Central Asian silks, among examples of other media:

As a decorative theme the motif of interlacing circles5 was a common one in Palestine. … It is found in Syria, and, although in a slightly different form, it was not unknown in early Rome. [References in notes 3 and 4 omitted.] It became a typical feature of early Byzantine decoration and of the art of Coptic Egypt. It also belonged to the Iranian decorative vocabulary, as it is seen on a stucco border from Hira [Note 2: D. Talbot Rice, “The Oxford Excavations at Hira”, Ars Islamica, v. 1 (1934), fig. 9 opposite p. 58.] and on some Sasanian textiles. [Note 3: Sarre, Dir Junst des alten Persien (Berlin, 1922), pls. 95, 99.]

However, the excavated ruins at Ḥīrah are dated to the eighth century by coin finds and their decoration cannot be assumed to reflect “the Iranian decorative vocabulary” (that is, repertoire) without further examination. In fact, the evidence shows that the guilloche is not Sasanian.

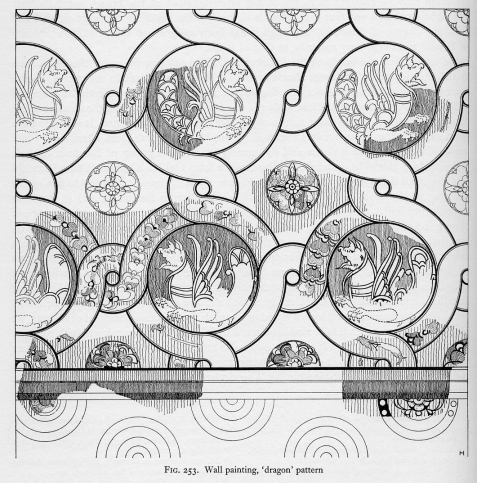

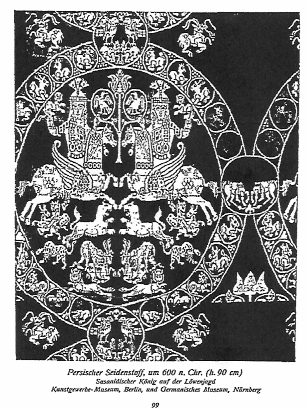

Grabar also failed to note that neither of the two Sasanian textile comparisons has a guilloche net as its frame. Sarre's pl. 95 is the “Sënmurw Silk”, Victoria and Albert Museum no. 8579-1863; his pl. 99 I reproduce below.

Figure 2. Sarre's pl. 99. |

In the textiles Grabar cited the roundels do not interlace. They are arranged in rows and columns perpendicular to each other and identically spaced. At the points where they would touch they are overlapped by small disks or other devices covering the borders of each pair of adjacent roundels. This is one of a variety of approaches to a roundel lattice found in Persian, Central Asian, and Chinese silks, large numbers of which have been published in the last few decades. In some such cases the roundels are entirely separate; the spacing can vary. In none of them is there any interlacing of roundel borders. In fact there is little or no interlacing in Chinese art up to at least the Yuan. The interlacing characteristic of Islamic art comes from its Late Antique roots, and the guilloche net is a venerable Antique pattern.

By contrast, Byzantine silks with guilloche nets (and Byzantine roundel fillers) are well published, and the difference between interlaced and not-interlaced roundel borders has been noted in the literature. For an example see the Annunciation silk in the Vatican Museums, no. 61231.

I conclude that the guilloche net pattern comes from an Umayyad textile in which the sīmurghs were domesticated in an Antique frame.

The field below the sīmurgh gullloche net, which is a lattice of roundels bordered by “pearl” bands. has parallels in Chinese silks, though I have found none that employ the same flowers or lack interstitial motifs.6

In the Chinese silks with roundel lattices that I have found the lattice is a square one: the roundels are aligned vertically and horizontally and are equidistant from each other. In both instances of the roundel patterns at Khirbat al-Mafjar the lattice is a rhombic or equilateral triangular lattice: the roundels are laid out at the intersections of a grid of two sets of diagonals meeting at angles of 60° and 120°, or, equivalently, at the intersections of a grid of three sets of lines, one of them vertical, that meet at angles of 60°. I have not found a Chinese example of roundels arranged in this way, but the rhombic lattice exists in Chinese textiles, so perhaps there was a textile source for the roundel pattern.

In summing up the decoration of the room above E2 Grabar wrote:7

We might therefore suggest that the Khirbat al Mafjar fragments represent a translation into painting of textile themes also found in stucco, stone, and even metalwork. … All that can be said with a fair degree of certainty about these four motifs is that they show—with one exception—essentially Sasanian textile influences and that they were probably meant to imitate the arrangement of a Sasanian palace room.

In that very guarded conclusion Grabar allowed for the possibility that textile patterns were imported via other media, and he referred to Sasanian stucco programs. But he clearly saw the origin of these patterns in textiles, and imagined them on walls:8

Although the evidence is comparatively slight, it is very likely that the decoration of ceremonial rooms in ancient and early medieval palaces often consisted either of huge tapestries hanging on the walls or of motifs imitating tapestries.

About another pattern, the rinceau, Grabar noted:9

it might have occupied part of a wall, or the whole wall, or the ceiling, or even the floor.

The question Grabar was dealing with is how the paintings were meant to be seen. One possibility that can be ruled out for the guilloche net pattern is that it was part of a figural painting that showed clothing or draperies, as there is nothing to indicate folds.

The guilloche net pattern could have been intended to be seen as a representation of a textile hanging, with the roundel field part of its border.10 Most surviving hangings from the Umayyad period seem to be figural, but a possible hanging in the David Collection suggests remotely that the guilloche net pattern could have been seen as a picture of a hanging if it had been framed appropriately.

Hamilton's reconstruction drawing of the guilloche net above a field of rosettes looks to my eye like a dado of fabric (rosettes) and a main wall surface of fabric (guilloche net) above it. Was the viewer supposed to see the painted fields as depictions of real yardage installed permanently? temporarily?

I believe there are no Early Islamic depictions of fabric as dadoes. Early Islamic architecture followed Late Antique precedent: the dado was typically marble or a depiction of it, and above the dado the usual decoration was figural painting,

In any event, trying to see the guilloche net and roundel patterns as representations of fabric is too literal an approach. The use of textile patterns in Byzantine decoration was described insightfully by Anna Gonosová:11

The south vault [of the Church of St. George in Thessaloniki] has already been considered as inspired by late antique silks. H. Torp, for example, compared it to a kind of baldachino that was placed over the entrance of the newly converted church. But neither Torp nor other scholars were concerned with the formal peculiarities of the south vault itself. They did not go beyond pointing out a general model for the decoration, which was identified as a textile, most likely of Sasanian origin. I believe that a textile, specifically a patterned silk, was imitated here mainly for its intrinsic formal and visual characteristics. …

In conclusion, the appearance in the MEditerranean area of the structured floral semis and the diagonal diaper in mosaics and other media furing the fifth century coincided with a more frequent use of the patterned silks themselves. Clearly, then, the influence of the textiles went beyond individual imitations and may have directly influenced the very formation of these patterns. The Early Byzantine floral diaper apptern and the structured floral semis can be considered, therefore, if not always direct imitations of textiles and silks in particular, certainly as a timely attempt in the area of ornament ot achieve a similar effect: the effect of all-over surface definition. Extant Early Byzantine monuments suggest that the visual appeal of all-over, surface-defining patterns was a more general one, and that the ornamental effect produced by patterns such as the two discussed here can be considered a characteristic mode of the period.

That is, the pattern is independent of the medium. Just as a textile pattern could be rendered in mosaic, so too in paint, giving the entire surface a substantial or insubstantial quality. Gonosová wrote of vault and floor decoration, but there are Byzantine examples of all-over or field patterns derived from textiles applied to vertical walls, too.12

It was characteristic of Late Antique architectural decoration to apply field patterns to walls to give them a rich and continuous visual texture, They were used inside the entries to both the palace and bath at Khirbat al-Mafjar in fields of carved stucco, although those are not all textile patterns. And, unlike in Byzantine architecture, Umayyad architects applied field patterns on exteriors, as on the entry to the palace at Qaṣr al-Ḥayr al-Gharbī and the Khirbat al-Mafjar bath porch, in association with figural sculpture.

Da'adli reconstructed a large painting of a triumph, placing it in the second-story room over the palace porch. That would have been a room where the owner of the palace met with visitors. The room with the guilloche net painting would have been private, and it had painted decoration in other textile patterns (possibly excluding the rinceau). We cannot know how they were arranged,13 but the effect must have been rather novel: not that of a room “hung with silks”, but a room of expansive patterns of different sorts. Given the high degree of originality in Khirbat al-Mafjar's deccoration this collection of patterns must have been varied intentionally.

1. Matteo Compareti

has argued that these animals have been wrongly conflated

with true sīmurghs and calls them pseudo-sīmurghs,

“Ancient Iranian Decorative

Textiles”,

Silk Road Newsletter, v. 13,

2015, pp. 36–44, available as of November 2020 at

http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/vol13/Compareti_SR13_2015_pp36_44+PlateII.pdf.

2. Dmitri Baramki, “Excavations at Khirbet el Mefjer. IV”, Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine, v. 10, 1942; Robert Hamilton, Khirbat Al Mafjar: An Arabian Mansion in the Jordan Valley, Oxford, 1959; Tawfiq Da'adli, “Reconstructing the Frescoes of Khirbat al-Mafjar”, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, v. 46, 2019, pp. 247–90.

3. Exactly where is unclear. According to Grabar's contribution to Hamilton's Khirbat Al Mafjar they came from E2 (p. 296, second heading; p. 297), which was Hamilton's designation of the room in the northeast corner of the palace on the ground floor. According to Da'adli they came from the next room south (number 4 in his incomplete enumeration of the rooms), corresponding to Hamilton's E4. Baramki, op. cit., pp. 157–58, listed all the rooms on the east side of the east block except the southernmost one as findspots of “stones with frescoes” and added that as there were “no signs of frescoes” on the walls of the ground-floor rooms “it is thus safe to assume that these frescoes came from the rooms and galleries of the collapsed first floor”. He did not indicate what designs were found where.

4. Pp. 297–99.

5. Circles do interlace in this pattern, but they are not the circles enclosing the large filler motifs. Instead, they are circles deformed as squares with concave sides and rounded corners that interlace with other such forms, actually enclosing the small filler motifs.

6. Grabar described another instance of a similar pattern as the “rosette motif” and conflated it with the instance below the guilloche net (pp. 299–300):

That fragment is illustrated on pl. 70, 6, which matches the lower left fragment of the guilloche net pattern as shown in fig. 253.The rosette motif (Pl. LXX,7–9; Fig. 254). Six fragments from this area in the palace show an all-over motif of large rosettes (c. 18 cm. in diameter[sic]) within rings set in a diaper pattern over a light background, now discoloured. [Note 1: Among the fragments found in the same area there is one which shows a smaller and simpler rosette, not unlike those of the “diamond’ pattern and apparently set within a hexagon. A similar type is also found in Samarra: Herzfeld, Malereien, pl. xliii, no. II.] The rings are of a very common Sasanian type, black with white dots. [Note 2 cites Sarre and Herzfeld, Am Tor von Asien and Malereien.] One fragment shows that the rosette motif touched the lower edge of the dragon pattern (Fig. 253).

The scale of pl. 70, 7–9 appears to apply to all three of those fragments, and possibly to fragments 1–6. But the rosettes on fragments 7 and 8 are respectively a bit under 17 cm. and a little over 19.5 cm. in diameter. According to that scale the disks painted with sīmurghs in the guilloche net are about 22.5 cm. in diameter. If that is so, then the rosettes below the guilloche net pattern in the unscaled fig. 253 are a bit under 17.5 cm. in diameter.

7. P. 306.

8. P. 305.

9. P. 302.

10. Sabine Schrenk discussed how to determine whether a textile could be a hanging and surveyed extant hangings in the Abegg-Stiftung collection in Textilien des Mittelmeerraumes aus spätantiker bis frühislamischer Zeit, Riggisberg, 2004, pp. 459–62.

11. Anna Gonosová, “The Formation and Sources of Early Byzantine Floral Semis and Floral Diaper Patterns Reexamined”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, v. 41, 1987, pp. 227–37, pp. 236–37.

12. Philipp Niewöhner and Natalia Teteriatnikov, “The South Vestibule of Hagia Sophia at Istanbul: The Ornamental Mosaics and the Private Door of the Patriarchate”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, v. 68, 2014, pp. 117–56.

13. Ignacio Arce has reconstructed the pattern of a wall painting of noninterlacing sīmurgh roundels with “pearl” borders from Qaṣr al-Ḥallabāt, but there is no clue to its disposition (“Hallabat: Castellum, Coenobium, Praetorium, Qaṣr. The Construction of a Palatine Architecture under the Umayyads (I)”, Karin Bartl and Abd al-Razzaq Moaz, eds., Residences, Castles, Settlements: Transformation Processes from Late Antiquity to Early Islam in Bilad alo-Sham, Rahden, 2008, pp. 153–82, fig. 20).