World Beat Report Santos

Tanaka Wong

Vitale

Goerlitz Quon

Almeida

Gaffney

Directory

A LIFE

LIVED WITHIN

THE HISTORY

OF BAY

AREA WORLD

MUSIC

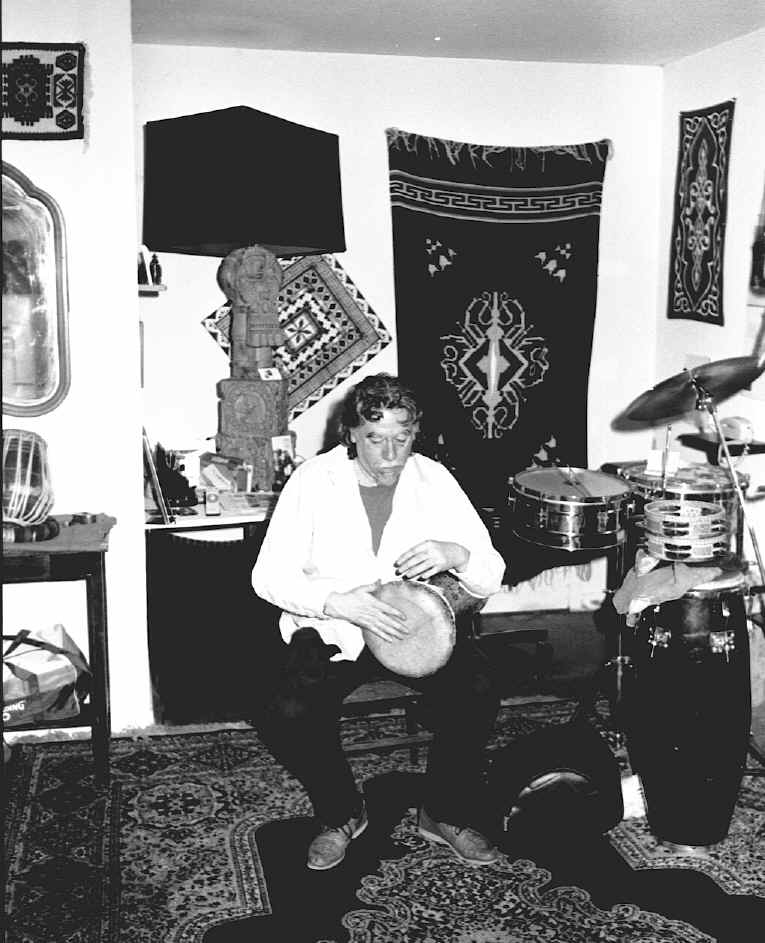

VINCE DELGADO

Few, if any, individuals, can rival Vince Delgado either in the immediacy and breadth

of his knowledge of San Francisco Bay Area world music or in the contributions he has

made to the same as a performer and teacher and through a short stint as

executive director of San Rafael's Ali Akbar College of Music. Longevity

certainly plays an important

role in his prominence: his musical progress has lasted for more than 50

years and shows no signs of abating. But the passage of the decades

would have had far less of an impact had not time and talent taken him on a road less

traveled and on a musical journey for which the term "odyssey" is

particularly apt. Though his travels were for the most part confined to

local settings, he experienced very early on how, within the greater Bay Area,

the cutting edge flavors of jazz and experimental music and the classical music

of Japan, China, Arabia, the Mediterranean and elsewhere could both be heard

live on a regular basis and studied under exceptional teachers. In his own

artistic and professional development, he eventually came to place the greater

emphasis on Middle Eastern percussion, but along the way to sterling

achievements in that idiom, some of which are captured on his Dangerous

Rhythms and Remembrances recordings, his pursuits took him along

byways leading to places as remarkable as they were rewarding.

WBR: You have an exceptionally long term perspective on the rise of world music throughout the greater San Francisco Bay Area. Pick up the story as early as possible.

DELGADO: I grew up in the mid 1930s in San Francisco=s Mission District down on 24th and Fulsom. It was heavily Latin, but not as heavily Latin as it is now. Those days you could find a German butcher on 24th street; in fact I worked for one, you know, kid stuff. There were some Irish, because I had Irish schoolmates. I knew some Greek kids in high school. So it wasn=t quite as heavily Latin as it is now. Now it=s just like going to a Latin country.

There weren=t any nightclubs on Mission Street that I knew of, just regular old bars and that stuff. See I grew up in the time of the movie theaters. There were six movie theaters on Mission Street between 16th and 24th. My mother would give me a nickel on Saturday mornings; matinees you know. That=s what kids did on Saturday morning. They=d go and hang out with other kids and make noise and go to those matinees and see a couple of features, the news, and 10 shorts--the next chapter of Flash Gordon or something like that.

WBR: So how did your musical education begin?

DELGADO: Mine begins from the radio. That was my heavy influence because there was a program that came from Oakland--I don=t remember the name of the station--but they use to play blues and jazz and swing a few hours every day. I just chanced on it. I listened a lot to Big Sid Catlin and Baby Dodds and all those people, Gene Krupa, Benny Goodman, a lot of black artists. Somehow I fell in love with that music. I don=t know why. My background certainly wasn=t that music. The music that I heard in my family was mariachi. But also, in those days, before the record industry was happening so big, you would hire a trio to go play. No matter how poor you were, if you had a big event, a Confirmation, or an engagement or something, you hired a trio to come and play in your house. To tell the truth, I can=t remember what kind of music it was, because I was so young, but that=s what happened. Right in our living room. We were, at the bottom of the economic ladder, real poor, but that was what was happening.

My family didn=t have any relationship to jazz, but that=s what influenced me early on. I wanted to be a jazz musician. This was when I was about 12. So I taught myself how to read music and play. I attended Mission High where I started trap drumming and continued from the 10th grade to the 12th grade. At that time there were no other drummers and I did everything. I did the dance band. I did the orchestra. I did the marching band. I played for the spotlight show, and all the operettas. We used to do Gilbert and Sullivan. At that time there was a teacher who really loved that stuff and once a year she would organize a show.

I was also playing in a big band in high school. We would work different high schools. It was a large dance band: four saxes, four trumpets, four trombones. The leader was an accordion player. He was just another young kid, but he was one of those guys who was an organizer type. So he was the band leader, he got this band together and he would get gigs at high school dances. We had a circuit. At that time there were other big bands, because there were kids who were into Stan Kenton and Woody Herman and Chevy Jackson. Then there was the Wilbur Brown Band. Wilbur Brown was the elevator man at Sherman and Clay on Kearny Street. There was a community center in Japanese Town--the area was Black and Japanese thenCand every Tuesday his big band would rehearse there. And he would get gigs. He would transport 20 people to San Juoquine Valley to do a jazz gig. He would do Dizzy Gillespie stuff, Dizzy Gillespie had a big band for a long, long time; Woody Herman stuff. I don=t know how he did it, but he managed to get all those people together.

So we were just emulating these people. All these kids would get together and try to have a big band. It wasn=t just the combo thingCthat was happening tooCbut it was also the big band thing. The band I played with did not do that kind of music, it was more for dance. I played professionally a bit with local big bands. I played bongos with some jazz groups, >cause that fit. I was doing bongos because, see, when there was a better trap drummer than me . . . there=s always somebody better than you . . . then I would do hand drums.

So I always had that hand drum thing. And even then my interests were becoming more and more inclusive of the other parts of the world. Somehow, early on I realized that the music I was hearing wasn=t the only music. There had to be music from everywhere. Everybody has their own music, like they have their own food and own clothes. And my interest never stopped, so that=s why I later ended up studying music from India, which I studied because I actually loved listening to it. A lot of people listen to it and don=t like it. I loved it; I don=t know why. When I first heard the sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan play, his music made me think of some many things. I heard in it flamenco. I heard in it jazz. I heard all these things in there. That=s when you know nothing, when you don=t know what a raga is. You just experience the music. That=s what I heard and that intrigued me too. How come I was hearing all this stuff in there? But it=s interesting that I lost that after I got to know the music, what the raga was and what was happening. Then I lost that other thing.

WBR: Did you encounter jazz in the Fillmore District then?

DELGADO: Yes. What happened was a few years later, when I was 14, I discovered bebop. I was totally enamored of it, just because of its avant-garde feeling. It wasn=t like Benny Goodman and swing anymore. I remember hearing the first albumCNew 52nd Street Jazz I think it was called. There were four 78s in this album. It was different groups with Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Max Roach. I had a very good friend who also loved music. Having listened to swing, the first time we listened to bebop, it was so new we could not figure it out what the hell they were doing with the chord progressions and stuff. The fact that we couldn=t figure it out made the music more intriguing. We ended up one night turning all the lights off and just listening to this music over and over in the dark. And you know what? Bing! The light went on and all of a sudden it made sense and we understood what they were doing. And when we understood it, we were so happy: we were going to play this music.

So I=d do all my high school music, and then in the after hours I=d go to the Fillmore. There were three major places: Jackson=s Nook, Bop City, and L. C.=s Breakfast Club. Jackson=s Nook was on Buchanan and Sutter. It was owned by an older black couple and during the day they served this different kind of food, like Chinese food but done in their style. But in the back room of this restaurant was a piano and a dilapidated set of drums. Some nights nothing would happen, but nothing would ever happen at all until after 2:00 a.m. A lot of famous people would end up going there. Jazz musicians would come through and they=d do their regular gig at some jazz club and they=d go there, eat, and if a session was happening, they=d sit in.

Wow! I=d just hang around and hang around and wait and wait. And once in a whileCif they were desperateCI got to play traps. But if a heavy came in, then I didn=t play traps. If there were some bongos around, I=d play those. But if a heavy bongo player came inClike Armando Peraza would come in once in a whileCI wouldn=t even play the bongos. But just the fact that I was in an environment hearing all these people play . . . .

Bop City was originally AVout City,@ and it was owned by Slim Gaylord. He made up that word. He closed it down and sold it and it became Bop City. Elsie=s Breakfast Club was an upstairs thing. Those were the places. You never knew when anything was ever going to happen in any of those places but you took your chances. You went to one. If nothing was happening, you went to another one. With redevelopment, all that got lost.

When I was about 18, I began the study of classical Japanese music for five years. I was interested in Oriental philosophy and that kind of thing. I found this wonderful 80-year-old teacher who taught the Samisen, a three-string, long-necked, banjo type of instrument that is used for everything from folk music to pop to classical. she married a farmer in Japan and they immigrated to California; they were down in the San Jose area growing strawberries. For 30 years this woman never played music. And then he died. Then she remarried, to a man who owned a Japanese newspaper in Japanese Town. Her house was on Sutter Street. So now she didn=t have to worry about money, she didn=t have to work in the fields. She knew everything. She knew flower arrangement. She knew tea ceremony. She knew classical Japanese music. And she knew all the partsCthe two koto parts, the shakahasi part, the samisan, and all the wordsCall by rote. She had nothing written down. It was all something she had learned as a child. And then she went for 30 years and did none of it. She raised her kids. By the time I met her she already had grand kids.

I had never heard her play. I didn=t know anything about her, but a friend and I heard that she was teaching. She required you to come three times a week and she charged $10.00 a month. It was something I could afford: right? Her way of teaching was that you came, you sat down, she didn=t tell you that when you tuned your instruments they were tuned to fourths or fifths. She just said, Athis note.@ She never said what they were; it was just one of the tunings. She would teach you a piece of music until you could play it. AYou can play it? Ok, bye.@ After you learned it, you got the next little section. So you kept doing this. Pretty soon, before you knew it, if you practiced at home, you=re playing a piece of music. Some of the pieces were really long, 15-20 minutes long. And you had to sing. I didn=t know Japanese. I had to write all the syllables down phonetically. So I learned how to play that way and ended up performing with her at Japanese events, little Japanese classical musical concerts.

Then I got into San Francisco State, where I got my Bachelor degree in art. I almost became an ethnomusicologist, almost. But I didn=t because academia didn=t quite agree with me. My best buddy, Robert Garfias, did. He went on but he doesn=t even play music anymore. Which is one of the things I was afraid of for myself. I enjoyed playing music so much and the academic thing just took away too much time. To study and to learn how to talk about music takes a lot of time. I would have had to have gone for a Ph.D, because that=s how far you have to go if you=re going to be a ethnomusicologist.

But S. F State is where I met some Arabs, one of whom became one of my best friends. Again, it was luck on my part because there=s no real space for Americans to do what I did. If you go to a Middle Eastern nightclub anywhere, they=re all going to be Arabic, or Turkish, or Armenian, or something like that. Normally, they=re not going to be Mexican. The refugee and immigrant experience had gotten big because of all the turmoil in the Middle East and many accomplished musicians came to this country. So the clubs weren=t desperate for some guy who knew how to play a little. The reason I got to play with the two Arabs I got together with in beginning is because we liked each other and we used to jam during lunch time. I=d play bongos and they=d play their traditional drum . . .

WBR: . . . the name of the drum?

DELGADO: It has many names. In Egypt, it=s called Atabla.@ ATabla@ means Adrum.@ But it=s a particular kind of drum, derivative of a clay pot with a skin across the opening. This is the drum used in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Palestine, Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Libya. But, of course, that word Atabla@ appears in India too. I think it=s an Islamic word, but Zakir thinks it=s not. See, we don=t know if the word came to India from the Middle East or from the Middle East to India. The Indian tabla and the Egyptian tabla, however, are distinctly different drums.

WBR: OK, so back to San Francisco State.

DELGADO: The basic thing was that my Arab friends and I liked being with each other. I learned their music from them and it was like on-the-job training. They could say, ok, this song has this rhythm, but couldn=t tell me how to play the drum. That I had to figure out by myself. When I was lucky enough to see bands that was passing through playing for the Arab community and I got to watch the drummers, that=s how I learned the techniques. It was all part of my education. If you see a drummer from the old country, then he knows how to play the traditional way. That=s how I learned. By watching them. As the clubs increased and there were more musicians, I was in on the ground floor. That was my training, at least for that kind of music. Though I didn=t know anything about Middle Eastern music at all, I never stopped. To this day, Eastern Mediterranean-Middle Eastern music has been my main focus. Though my training was originally in jazzCmy peers in high school were people like Vince GuaraldiCI didn=t stay in jazz that long. I did it about 10 years professionally and then I got sidetracked into Middle Eastern music and performed in Arab nightclubs for about 25 years, the Baghdad Cabaret, the Casbah, and Gigi=s Port Said.

I was in the first Arabic group that existed in the Bay Area, The Najibaba Trio. That=s just the name of the guy I met in college. His name was Naji and he was into being a personality, so he called himself Najibaba. We went to North Beach and jammed in The Cellar on Sunday afternoons. Then some person came up to us and asked if we would be interested in working his club, which was The Vagabond on Polk street. We played there Fridays and Saturdays and all the Arabs around would come and party. Later, we went to a club in North Beach. Then someone opened another club there. Before you know it, there were three or four nightclubs of Middle Eastern music and dance.

I eventually hated working the clubs. You end up playing six nights a week, five hours a night. Same music. Same musicians. You end up doing the same riffs. Pretty soon I hated my own playing. I didn=t have time, I was too tired after six nights, to go home and woodshed. So I would quit. I was at one place for six years, night after night with one night off. And I just left, I couldn=t take that anymore. They were all shocked. What are you quitting for man?; you=re making good money, you=re getting union scale. They couldn=t believe it.

Then I=d go back. In six months I=d need the money and work in another club with different musicians. Fortunately, when I worked the clubs in North Beach, I had a high school buddy who was the doorman at The Jazz Workshop. I=d get 20-minute breaks. For years, every break that I got I=d run over there and I got to hear everybody. I got to hear Coltrane and Miles and Aretha Franklyn. Mose Allison was there all the time. I got to meet Ben Riley, he was the drummer for Thelonious. That was something I really loved, hearing those people live. Just so many people.

WBR: Was there an extensive Arab-American community in the Bay Area then?

DELGADO: Yes, but they were largely refugees. That community didn=t get big until Israel happened. It also happened elsewhere. For instance, in Mexico, there=s a big, wealthy Lebanese community there. The people who owned the movie industry and textile industry in Mexico were Lebanese. About 20 years ago I toured down there with an Arabic band and met these people. They were very nice. In San Francisco, I worked in a nightclub called the Baghdad Cabaret, when the owner of the club got the gig. He was an Armenian-Arab violinist from Iraq. He took down an oud player-singer and me, the drummer, and couple of dancers, for a small tour of Mexico. We went to Yucatan and then we went to Mexico City. In Mexico City, the Lebanese have a center, a Lebanese club, which is a square block of Mexico City. Inside that square block is a park, with a swimming pool, stuff kids can play on, with buildings all around it. They have an auditorium, a dining room, bar, a place for classes to teach kids Arabic.

I=m sure it happens in other South American countries too. I worked in Bogata, Columbia for two months with an oud player, maybe 10 years ago, and I lived there, ate Arabic food everyday, in a really fancy Arabic club. The owner was originally from Palestine.

Before Israel, there were just a few Lebanese in the Bay Area. When Israel formed, that=s when it started to happen. There=s one particular town called Ramala, which many of them came from. So there was this big community of people from Ramala in the Bay Area. They had their own center on Ocean Avenue, where they had their wedding parties and all kinds of stuff. I=ve played there many times.

Now they have an Arabic Cultural Center. They teach Arabic there and they bring scholars over to talk, or authors, so that the Arab community is still able to function as Arabs. They do an Arabic festival once a year and the community=s gotten more organized. They wanted to have more of a voice. Americans have stereotypes of Arabs and Arabic culture. I think that=s what bothers them the most. They are also gathering to help each other in political ways too. Most of these people in the Bay Area are from Palestine. So they=re interested in improving their image, and also communicating with each other. That=s what the Arab Cultural Center is about.

WBR: Around this same time, you also connected with one of the more idiosyncratic figures in Bay Area music, Harry Partch, who achieved legendary status not only for composing especially innovative music but for inventing original instruments as well. How did that come about?

DELGADO: A friend I grew up with heard that Harry Partch was going to be performing a concert. We were teenagers at the time. He went to the concert and said, AMan, you should hear this guy=s music, it=s so far out.@ He went and met Partch who said, Ayeah, I=m looking for musicians to play my music.@ My friend said, Alet=s go meet the guy and see if we can play.@

So we went. Partch lived in Sausalito. He was a good friend of Alan Watts. There was this scene there. He was a very nice man and he was hot to get musicians. He liked us and we could read his music, which had some really weird time signatures, 10 over 16, and all kinds of funny things. Everything he did was distinctive. The instruments were not usual instruments. The way you=d hit them was totally different. You just had to practice his music. You had to go to Sausalito to work on it because you couldn=t take the instrument home. It was as big as a room sometimes. So I worked with him for a couple of years just learning his music. Then he made a record of it, Plectrum on Percussion. It was on see-through green vinyl, kind of thick. He had good musicians on it: jazz musicians, dixieland musicians, even a classical singer. He drew from everybody who was interested in what he was doing. He didn=t care what your particular background was. If you could do his music, that=s what he was interested in.

WBR: If it was hard enough to hear jazz on the radio in those days, was it at all possible to hear world music anywhere?

DELGADO: On KPFA. In fact, a man who later became another of my best

friends had a program on KPFA. His name was Henry Jacobs. He was a collector of

world music. He put a lot of African and Indian music on the air. No one else

was doing that. He would tape it at home and take the tape to the station and

play it. It was a regular program, every Sunday. He didn=t

know much about the music but h e knew he liked it. He would just give you the

title and where it came from, what label it was on.

e knew he liked it. He would just give you the

title and where it came from, what label it was on.

Later, I went to a party at the Academy of Asian StudiesCI think it was the name of it. It was a University of The Pacific extension and the Dean of the Academy was Alan Watts. People like Gary Synder were there. Alan was bringing people from different countries to teach. He had a calligrapher from Japan who was a monk, who actually started the Zen Center; his name was Tobase. Then there was a Chinese scholar who taught Chinese philosophy. Everyone was curious and you had these scholars from different countries.

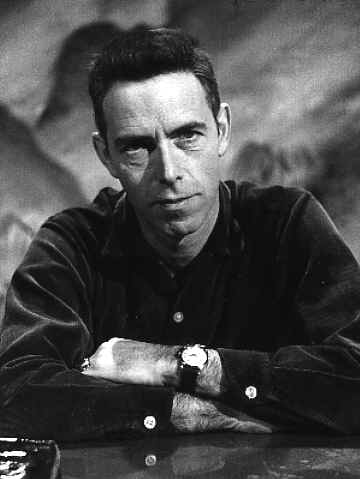

Alan Watts (1915 - 1973) The value of Watts' contribution to the

confluence of thought, experiment and social action that manifested

so vividly during the middle 20th Century is difficult to overestimate.

Principally through an extensive body of writings and taped

lectures, Watts reigned as one of the foremost interpreters of

Oriental tradition to individuals open to spiritual inquiry. Among

Watts' great strengths was his ability to make his offerings engaging

to a degree that a reader or listener often felt impelled to look

elsewhere for more. One could go from Watts' The Way of Zen

to a classic such as The Zen Teachings of Huang Po because

Watts made movement in that direction so inviting. If he

accounted for your early exposure to varing ways of thought and

differing world views, you were well placed and in good company.

At the time, I wasn=t enrolled because I was kind of young still. But I went to this party and I heard this voice and I said AI know that voice.@ I saw the back of this guy. He was in an Ivy League suit. It turned out to be Henry Jacobs and the reason I knew the voice is because I had heard him for years on the radio. He was kind of a charismatic character. He had met Mongo Santamaria, Willie Bobo, and they used to hang out at his studio. You'd pass through and there would be Mongo Santamaria recording.

So I went to talk to him and eventually we became real good friends. He turned me on to Ravi Shankar when nobody knew who Ravi Shankar was. In fact, he got Ravi Shankar to go to his house and make a special recording for him. If you can imagine that Ravi Shankar would even do that. But in those days Ravi Shankar would do a concert at the Museum of Modern Art, or wherever, and 90 people would come. And he did this for years, Ravi Shankar did, before he blossomed with the world's awareness of that music.

WBR: Did that mark your transition into your association with San Rafael's Ali Akbar College of Music?

DELGADO: Not quite. There was this Society, these wealthy people who had money and who brought Ali Akbar Khan here. They knew who the Bay Area people were who were interested in ethnic music. So there=s that connection. There was bunch of people who were interested in Eastern European, or Balkan, or Macedonian music, and Greek, and Turkish. So this Society asked them, if they brought these musicians from India, would they be interested in studying? Some people said yes, though not many.

In 1965 they were having Indian music and dance taught in Lafayette at the Scripp=s home. They had a dance teacher from Southern India, very famous, Balasara Swati was her name. She brought a drummer and a singer and a dance master and she taught dance. And they brought Ali Akbar Khan and a tabla player, Shankar Gosh. Ali Akbar Kahn had five students. For a whole month, Shankar Gosh had nobody. Then I showed up for a month. I had gotten into Indian music from records that I had heard, so when the Scripps brought those people over, I went, but I was the only drummer, because people didn=t know. Then the dancers and musicians left.

They came back in >66. What made it successful is that that year Ravi Shankar connected with George Harrison and the Beatles. All of a sudden, everybody knew. So whereas in 1965 Ali Akbar Khan had five students, in 1966 he had 60. Whereas Shankar Gosh had one student, me, the second year he had 30. Boom!, it went just like that. One of the people in my drum class was Richard AlpertCBaba Ram Dass. Nice guy. He used to drive one of those fancy old cars.

Then in 1968 Ali Akbar Khan started his college in San Rafael. I was on its board of directors and became its first executive director by default. Everybody else on board either didn=t want to do it, or got sick, or something happened. So Ali Akbar Kahn asked me. I said Aok.@ I didn=t have any experience running a school, but I did it. I didn=t play music for a year and a half. All I did was . . .

WBR: . . . it was your academic nightmare come true.

DELGADO: Right! And I just like collected money and sold instruments and bought instruments, and took teachers shopping and gave them their pay, and took care of the books, and all that kind of stuff. After a year and a half, I said Await a minute.@ And by then there was somebody else willing to do it. I studied Indian music for about 13 years very seriously. And though I had learned a lot of Middle Eastern music, I feel like Indian music is where I got my real knowledge of rhythm.

WBR: What are some of the key distinctions between the Middle Easter and Indian styles of drumming?

DELGADO: In Indian music the goal is improv. You have set rhythm cycles and rules, and you have set things about the melodies, the ragas. It isn=t like jazz, where you can blow a note that=s not even in the scale. In Indian music you can=t do that. But what you=re supposed to be doing is making it up as you go along, within the rules. So in that sense it is akin to jazz. In Middle Eastern music, you have parts where you do improvise, but a lot of it is set music. They=re tunes. Some of them are complex tunes, or maybe in weird times, but nevertheless it=s set music. Whereas in Indian music, you go through all this stuff to learn what you can do. There are a lot of ways to approach improvisation. But improvisation is the goal. That=s the big difference between Indian music and Middle Eastern music. In India, they don=t just say, Aimprovise.@ They say, ALook, if you want to improvise, instead of doing four hits per beat, you can do five, or seven, or nine, or eleven. Or you can do five beats over two.@ They have explored the mathematics of its extensively, because the tradition=s been around two to three thousand years. The teaching is all oral. They show you how to do all these far out things and you don=t even know you=re doing them, because the teacher just says, you do this, you do that.@ It=s not theoretical, it=s practical. You learn how to do it, and when you analyze it, you learn that you=re doing some pretty far out stuff, which if you wrote down in western notation, you wouldn=t even be able to read the notation.

Part of the vehicle for that is the language of the drums. In Indian music, the language is very specific. The sounds are articulated. In tabla, every stroke you make has a specific sound. There are about 20 different sounds. So the teacher tells you which sounds and you know how to hit the drum. It=s a way of transferring rhythms, this particular language, which is actually very standardized. Through these sounds you make verbally, you can converse with any drummer who has studied tabla or classical Indian music. You don=t need a drum. You can pass compositions to each other without drums.

Arabic music is a non-harmonic music and is music based on what they call Amakam.@ That word is the same word as Amode.@ A mode is based on a scale. You can have a scale, but you can derive different modes from the same scale using all the very exact same notes. The raga system is kind of the same. But you make these rules. For example, you say, in this mode, when you go up the scale, you don=t play the third note. When people first hear Arabic music, they say, AOh, it=s in a minor key.@ Well, the truth of it is that in Arabic music and Turkish music, minor is one mode that they use. Major is another mode that they use. And then they have 30 others. And the way they do that is the way they work with the scale. They play notes that are Ain between the cracks of the piano@; that=s the way I like to explain it. There are other notes. The piano is based on whole steps and half steps. Well, you have a half step, then you can have a quarter step. In Arabic music, they use these quarter steps. They do not exist on the piano. They do not exist on guitars, because of the frets. But they do exist on a violin, because you can play any note you want on a violin: there are no frets; it=s just where you put your finger. It=s the same thing for cellos; for basses; for ouds: none of these instruments have frets. The kanun is built to play quarter steps. The point is, if you know an Arabic song and you try to play that song on a piano, it will drive you absolutely nuts. Because the quarter tones can=t be played, the song will sound completely out of tune. It=s a complex subject. There are many scale and many modes.

WBR: How does the Grateful Dead=s Mickey Hart become involved with the Ali Akbar Khan College of Music?

DELGADO: Actually Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann. They just showed up at the school one day. I was still executive director and had to raise money, that was one of my jobs. So out of that meeting came this benefit at the Berkeley Community Theater. One night was Ali Akbar Khan and Shankar Gosh, his drummer. And the other night, the Ace of Cups, the Steve Miller Blues Band, and the Grateful Dead. At the time, there was a tabla student at the College who was the girl friend of Owsley, who does sound for the Grateful Dead.

One of the things we did at the concertCwhich, by the way, was actually f ilmed by someone from Crosby, Stills & Nash; one of those guys actually sent two cameramen up for this concert, and I would love to get my hands on that film but I don=t know where it isCbut anyway, at the end of the last song the Grateful Dead did, the platforms they were on were separated and I and my teacher, Shankar Gosh, were moved forward. Shankar Gosh played tabla, I played the doumbek, and we did a jam with Bill and Mickey. We had put it all together beforehand, said ok you=ll do this, I=ll do this, we took turns, we did a unison thing, the whole trip. That was the last number the Grateful Dead did. The Dead were not yet superstars but the place was packed. We did this unison thing and stopped. And the crowd went absolutely wild. I felt like my childhood dream: I finally made it as Gene Krupa. It was the beginning of that kind of fusion: a Middle Eastern drummer, an Indian drummer, and two rock and roll drummers, all on the same stage jamming with each other.

WBR: Which shortly thereafter continued in a world rhythm band called Diga, yes?

DELGADO: I=ve always thought of Diga being a unique event that will never happen again, because of the way it was done. We had one Afro-American conga drummer, Jordan Amarantha; the Middle Eastern influence was mine, the Indian influence was Zakir Hussain and his students. Mickey Hart brought rock-and-roll and jazz. That=s what it was: everybody threw in everything. Zakir threw in classical Indian drumming, plus folk Indian drumming. Joy Shulman also played tabla. She eventually gave that up and went on to become a conga drummer with a band called Mapenzi.

Delgado, with Zakir Hussain

Where Diga really came from was my teacher, Shankar Gosh, who wanted to have a class that just involved drummers. At that point, we had about 20 drummers. Everybody brought the stylings they were studying before they played tabla. But it didn=t quite work as a cohesive group because of so many people and because we didn=t spend that much time on it.

But when Zakir came to teach, we started to do it again. This time we had a smaller group. That enabled us to start working on things seriously. We started to perform. It just developed. Then Mickey came along. He took this school orchestra, joined it, and because he had all the connections with record companies, we went to work seriously to make a record. Mickey got some money. Then he had us come to his barn five days a week to practice. Getting the money out front, allowed us to go to the Grateful Dead=s ranch and rehearse all day and part of the night in the barn. Everything was rehearsed thousands of times. We did this for months, in order to make this record. Five days a week for months, because nothing is written down. Once you had an idea, then you had to convey it to everyone else. Then they had to work it out so that it fits. I can=t imagine 12 drummers ever getting together again and putting as much work as we did into that album. It was really a lot of work. It has so much to it. It was overwhelming, >cause we had to memorize everything, riff after riff, knowing where to put it in. Some of the pieces are very complicated and we had to remember everything. I could never be in a project like that again, that takes so many hours, so much memorization, coordinating, synchronizing everybody. It doesn=t seem possible.

WBR: Nonetheless, from then forward, you=ve managed to find time to continue to cultivate your music in all its variety, appearing with Zakir Hussain and the Rhythm Experience, which is something of a successor to Diga, and performing with your own Middle Eastern group, Jazayer, pursuing solo projects, and more. How does all that sort out?

DELGADO: Zakir Hussain and the Rhythm Experience rarely performs. I think because we=re such an unwieldily group; there=s so much baggage because we have so many drums. If it=s not local, Zakir likes to have three or four gigs, like a little tour, and that=s a much more difficult thing to put together. If it=s local, it=s no problem. Some years we perform a lot, because that tour thing will come together, and some years not very much at all.

WBR: The Rhythm Experience followed from Diga. How did Jazayer come about?

DELGADO: Jazayer is my ex-wife Mimi Spencer, my daughter Devi-ja, and myself. The group=s forte is Arabic music and Greek music. Mimi plays an instrument called kanun, a zither-like instrument. Mimi sings in three different languages. She speaks pretty fluent Greek and can sing a lot of Greek songs, so we can do Greek festivals or Greek folk dances. Devi-ja is a violinist and plays mostly Arabic music, with some Turkish music. Some Arabic classical music has been derived from Turkish classical music, because the Turks were in the Arab countries for a long time. Jazayer is then also anybody else we want who knows our music. My present girl friend, Coralie, plays oud and at times also performs with Jazayer and also designs my cd=s for me. Tom Shader is an acoustic bass player we work with. He just happened to be our neighbor for many years, so we taught him the microtones and stuff that you have to learn in order to play Arabic music.

Mimi was originally a classical piano player. Then she got into folk singing; Joan Baez was her idol at one time. Later she went to University of Washington, where my best friend, Robert Garfias, was head of the ethnomusicology department. He had Japanese court music there. He had Indian music. He had all different kinds of African music. All with teachers from those countries. She was exposed to all that. She loved it, and then Garfias said, well, you know they also have an Indian music program going on in the Bay Area. So she ended up at the Ali Akbar College in 1968 and that=s where we met.

The thing is, what happened was that I was in the Middle Eastern thing for many, many years. I learned that music and played and knew the inner workings of it and everything like that and a dancer came up to me and said, I=m doing this big show at the Cow Palace and I had this Persian guy and his friend who were going to play and now they=re not going to play, can you help me out? And I said, ok, what can I do, I=m just a drummer. So I went to my daughter and to Mimi, who also played the sazCit=s kind of a Turkish folk instrumentCand said, hey you guys, you know you can make some money? All you have to learn half a dozen simple Armenian tunes and you can get--I don=t remember what the pay was--and they agreed: AJust this one time, we don=t want to do it anymore.@ Mimi said, AI=m very busy studying Indian music.@ It=s kind of funny, because they both ended up doing Middle Eastern music for a long, long time and really getting into it and making money. So that=s how Jazayer started.

We were the first American group to play Middle Eastern music to Middle Eastern audiences. At first it wasn=t classical. We=ll do small Arabic parties, with 20 or 25 people. It=s a folk-pop music. Early Arab pop in the >50s, >60s, and 70s was different than pop is now in the Arab world. Now there=s a lot of synthesizers, rhythm machines, clap tracks. Back then, it was the traditional instruments; that=s a difference now. And in those days there were very famous composers who did all these songs on the radio and who were also movie stars. All the Middle Eastern people saw the films that they were in. There was this whole body of music that originated in Egypt and was very popular throughout the Arabic-speaking countries that had become standards that weren=t really Apop music@ in the sense of a short, little jumpy tune. The earlier popular music was more involved; a little more complex; that kind of music.

There=s also Arabic classical music, which has even way less audience, but used to have an audience in the >20s, >30s, and >40s. We play that Arabic classical music, although most people don=t know what Arabic classical music is. But we love it and that=s what we work on. We=re not learning anything else.

So it=s kind of an interesting situation here. When we get hired for parties, somebody always wants some jumpy stuff, but we don=t know any jumpy stuff. So we can=t play it. We present classical works. People hear us play and they like what we do, but they don=t realize that=s even classical. But they hire us for another little party, and we keep presenting them with the kind of music that was popular maybe 50 years and which goes back quite a ways. That=s where our interest is.

WBR: Where do you find Arabic classical music?

DELGADO: A lot of it is written down. Some of the forms come from Turkey and Turkey has a vast repertoire of classical music. So does Egypt and Syria and Lebanon, and it=s all written down in western notation. It=s a big body; of work, I got stacks of it, books; famous composers they come out with a book of their compositions; there=s a lot available.

WBR: Yasha? Hijaz? Kitka?

DELGADO: Yasha was like Jazayer joining with other Bay Area musicians who had an interest in Eastern European and Middle Eastern music, particularly Turkish music. It came about through a Turkish saz player and singer, Latif Bolat, who wanted to have a band, so he just called around to different people to see who was interested. Turkish music was something I had already done and we just got together. Hijaz was a jazz-based trio: guitar, bass and mostly hand percussion. I played congas, bongos, tabla, doumbek, and Egyptian tambourine in this group and composed a lot of the material. A lot of the pieces were in odd times, different modes, and had unusual twists to them.

WBR: And haven=t you presently also gotten back into jazz?

DELGADO: Not my big band swing jazz. I perform with The Murasaki Ensemble, which was was founded by Shirley Kazuyo Muramoto, a fourth or fifth generation Japanese lady who plays koto. Her mother is a classical koto player and she learned from her mom. Shirley=s very good and she also loves jazz. So for years she tried putting together some kind of thing in which she would compose music in an American style but she would use the bass koto--it=s a huge koto--and she tried it but it didn=t always work. Finally she decided that she would try to make a jazz group. I had already been playing with her but I was playing with a trap drummer. Then she had to decide: should I have Vince on hand drums or should I have the trap drummer? Well, she picked me. Then she got Matt Eakle. He=s a flautist who works with David Grisman. He=s wonderful. Then she got a bass player, Alex Baum, who plays with all kinds of blues groups and jazz groups, and an acoustic guitarist, Jeff Massanari, who does the same thing.

What she has are people who are knowledgeable in jazz, but with me and her as the odd ones. Right?, because I play all different kinds of drums. I play congas, and bongos, and I play my Egyptian tambourine and doumbek, in the group. We do a couple of jazz standards, but 90 percent of the repertoire is original music. Everybody gets to compose. So the group has all these influences, especially in my compositions. They=re not necessarily Middle Eastern, but they might have a Middle Eastern tinge to them. That group actually performs a lot. We=ve played Yoshi=s and sold out our shows.

I=m also playing quite a bit now with a piano player, Larry Vucovich. He=s originally from Yugoslavia. He studied with Vince Guaraldi. And a bass player, who=s also from Yugoslavia. We do a trio thing a lot and sometimes we do a bigger group. We did something at Bach Dynamite and Dancing Society with Eddie Marshall. Larry has written some tunes that have that Eastern European, Gypsy tinge to them. On some occasions, we=ll play a lot of Latin jazz, because I can play congas and bongos in traditional mambo style. If we pick a piece like ACaravan@ or ANight in Tunesia,@ I=ll play dumbeck and congas, to add those other flavors.

WBR: All the members of Jazayer, both individually and as the group, play regularly in Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern restaurants and festivals throughout the greater Bay Area. Share something of the more distinctive venues that all of you play at, starting with the annual Rakkasha Festival that=s been going strong for close to 20 years now?

DELGADO: You know what that is? It=s that belly dancing became so popular that at its peak that there are all these women who have studied the dance and who love making their costumes, but who have no outlet. There aren=t that many belly dance nightclubs. But if you=re interested in the art form and take classes, then what do you do? This woman, Shukriya, found the answer to that question. Once a year she=ll rent this huge auditorium in the East Bay for Saturday and Sunday and she=ll have dancers and dance troupes who want to perform sign up. So every 15 minutes is a new dancer who dances to either live or canned music.

Then there are vendors. So you walk into this huge auditorium filled with vendors selling glitter, scarves, bell dance costumes, cds, cassettes, drums, foods, kanuuns, flutes, videos. Hundreds and hundreds of people go there every day. There=s constant dancing. It=s a huge scene. Dancers come from all over the world. They come from Japan: belly dancing got big in Japan. They come from Germany: belly dancing got very big in Germany. The United States is saturated with belly dancers; there=s thousands of them.

WBR: I read that Mimi performs for the Mevlevi Order of America. What is that?

DELGADO: Mevlevi is connected with the Sufi tradition in Islam, which is the more peaceful, mystical side of Islam and, more specifically, the AZiker@ ceremony. I=ve attended this ceremony in Istanbul. Traditionally, what they do in Turkey, if you=re a serious Sufi is that everyone goes once a week to this ceremony. You go and there=s a Sheik there, which is the wise elder man. First, they sing religious songs expressing love and peace. After that=s done, five or six drummers come in, sit on the floor and pick a rhythm. The rhythm will be very simple. The people will sit there and chant AAllah, Allah, Allah,@ and they shake their heads and they=re all doing this in unison. They keep doing this and eventually they get more and more wild. These are common, ordinary people. These are dentists, store owners, whatever; this is what their religious ceremony is. The Sheik changes the rhythm as he sees fit. He=ll cue the drummers to go faster or slower. The point is you=re saying the word AAllah, you get into this kind of hyper-ventilated state and pretty soon people start to get pretty wild. The head gets looser and looser; the body gets looser and looser; and they leave. In another room, there may be whirling dervishes, another group of people spinning to the same music. Part of the congregation is sitting on the floor trying to go into trance. The other guys are wearing these outfits on a big dance floor, spinning around constantly, trying to go into trance. So that=s what Mevlevi is. They have them all over the world, wherever you have Sufis.

WBR: You=ve mentioned playing Mexico City; Bogata, and now Istanbul. Any other particular settings in which you=ve appeared?

DELGADO: This year (1999, ed.) Coralie and I went to Fez, Morocco, where they have a Sacred Music of the World festival every year, for a week. There is music every day in two venues. One venue is huge, four or five thousand people. It=s an old palace courtyard. The afternoon concerts are in another, smaller palace courtyard. These are very beautiful, outdoor venues. We got to hear lots of very fine music: Sufi music from Africa, Christian church music, religious music from Armenia. There was Moroccan music with 20 drummers and five singers. And Sunday night, the last night, was Clarence Fountain and The Blind Boys of Alabama.