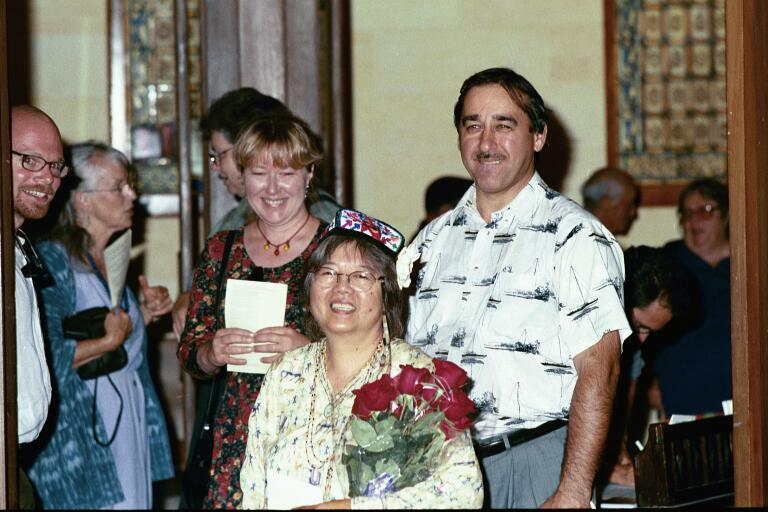

Betty Wong, following the 2000 premier of her orchestral work

"Dream of the Desert" at San Francisco's Old First Church

World Beat Report

Santos Delgado

Tanaka Goerlitz

Quon Vitale

Almeida

Gaffney Directory

MUSICAL

MEANDERINGS

ON THE SILK

ROAD

Betty Wong, following the 2000 premier of her orchestral work

"Dream of the Desert" at San Francisco's Old First Church

BETTY

ANNE SIU

JUNN WONG

boodwong@pop.mindspring.com

Professional credits for San Francisco=s Betty Anne Siu Junn Wong run the full gamut from producer and arranger to composer and multi-instrumentalist and with her first cd release, this year=s In Xinjiang Time, her combined talents in these fields have operated to place a stamp of Ashowcase@ over each of the 17 tracks comprising this rich mix of classic Asian folk instrumentals and Asian-inspired original compositions presented with unfailing virtuosity either by the full complements or by various members of two of the Bay Area=s most distinguished musical aggregates, Wong=s own Phoenix Stream Ensemble and the Melody of China Ensemble.

Xinjiang is a largely Islamic province of Northwestern China regarded traditionally as an autonomous governing region and home to a diverse community of ethnic groups that include Turkic Uygars, Tajiks, Kazaks, Mongols and Han Chinese. Occupying about a sixth of China=s land mass, the province historically served for more than a millennium as the central focus of the roughly 6400 kilometers of ancient Eurasian trade route that came eventually to be known as the Silk Road.

It is to the Silk Road that native daughter Wong turned for both inspiration and a unifying theme for an eight-year project that culminated in this ambitious and beautifully executed musical tapestry whose glistening threads echo sounds that centuries ago might have been evoked wherever caravans from the Middle Kingdom and the Mediterranean once crossed paths.

Regarding the Silk Road as much as a state of mind as a historical and geographic entity, Wong has, in her own words, created here a Adreamfield of American Eurasian nomadic music performed on a mosaic of international instruments from Xinjiang, Arabia, and China to America.@

Yet, on this journey of the Silk Road of the mind, the sensibility of the traveler is of an importance equal to that of the territory through which she travels. Born into a family that placed great emphasis on both politics and the arts, Wong began her musical training at age 7, emerging years later both with a master=s degree in composition from the University of California, San Diego and as an accomplished multiple talent on piano; guzheng, a string instrument resembling the koto; saz, a Turkish lute; kanjira, a South Indian lizard skin tambourine with a few jingles, and other instruments.

Her presence as a public performer began to be felt soon after as she became a founding member of the Flowing Stream Ensemble, likely the first regional troupe to bring traditional Chinese music to Bay Area audiences outside the Chinese community. She additionally gained recognition as a composer of film scores for the Academy Award-winning Allie Light/Irving Saraf movie producers and in 1988 received the Hollywood Dramalogue Critics Award for Outstanding Achievement for Original Music Theater for her work with the American Conservatory Theater=s production of Eugene O=Neill=s Marco Millions.

But yet again, for all her solid credentials and the accolades she has earned, perhaps both her greatest talent and achievement are reflected in her ability to draw a coterie of the most prominent figures in Bay Area world music into her projects, with the line-up of highly respected names joining her on In Xinjiang Time including Mary Ellen Donald, San Francisco=s maven of Middle Eastern percussion, and Mimi Al Khayyam (a.k.a. Mimi Spencer), renowned for her work on the qanun, a Turkish zither, and for her long performance history with two local Middle Eastern troupes, Jazayer and Yasha.

Therein lies much of the joy and accomplishment of In Xinjiang Time. As a producer, Wong emphasized supplying her coterie with an opportunity to display their best work. The result is that, altogether, 20 prominent world music performers each made significant contributions to a collection of stellar performances rendered according to the exacting standards that the artists have long demanded of themselves.

Six tracks are reserved for the classically oriented Melody of China Ensemble, or its various members, all recent arrivals to the United States who received their musical training from mainland China=s academies and conservatories. The Phoenix Spring Ensemble, or its various members, shines forth of the rest. Two of Wong=s original compositions are featured, one closing out the cd with a piece incorporating jazz lines, a testament to her outlook that the Silk Road can be followed as far as the traveler wishes to venture.

The lure of that ancient trade route was treasure. Centuries after the overland trek was displaced by sea trade, Wong has revisited its mystique and uncovered a measure of its bounty anew. In Xinjiang Time is obviously recommended unequivocally. The release may be obtained by mail order from Flowing Stream Ensemble, 1173 Bosworth Street, San Francisco, California 94131. Price information is a follows: $19.28, which includes the $15.00 list price and $4.28 to cover shipping, handling and sales tax. The title is also available at Amoeba Records in Berkeley and The Haight; San Rafael and San Francisco=s Borders & Books, and the City=s China Books, located on 24th Street.

Meanwhile, something more of Betty Anne Siu Junn Wong=s journeys:

WBR: So how did you begin to find your way to Xinjiang?

WONG: As a native San Franciscan who didn=t even realize that Cantonese was her first language. As an infant, I spoke English to the outside world and thought that was my first language. Well, it wasn=t. My parents never used English at home. So the first thing is that my bilingualism is really the seed for me to later accept music cultures that were out there.

But not only bilingualism. I was born of a generation when parents were still trying their best to keep an Asian connection alive with each child born on American soil. Both my parents were teachers of the Chinese language and my father was also a scholar and poet in the ancient tradition.

My mother dragged my twin sister, Shirley, and me as little kids to every Cantonese opera, every Cantonese black and white film. They were usually Acostumed epics,@ epic productions telling the great legends that are also the basis of Chinese opera. We learned a lot about Chinese history through the films. And like I say, never translated.

This is in the 40s, during the war years. We couldn=t get anything from China. And here=s the thing I didn=t know. As a kid, I gobbled up all the films thinking they were being made in Asia. It never occurred to us: where do you think they were made? But then it dawned on us after a while that in some of these movies, some of the people started wearing western clothes, while still speaking Cantonese. Well years later, to my shock, I learned that a lot of these movies were being made in Stockton, California.

WBR: Where did one see Cantonese opera in those days?

WONG: In the same bunch of theaters that are still standing today. One was called the Sun Sing and is now a mall on Grant right off Jackson Street. The whole time I was growing up it was one of the cultural places that the folks would bring their families to. But also embedded in Chinatown history are opera companies that are still very much alive to this day.

The culture of Chinatown was also radio, the Golden Star radio. I grew up with it. It was like the staple. Golden Star, as far as I know, was only a night-time radio. And it was only in Cantonese. It broadcast music, commentary, short stories, comedy. The comedy was very funny. The Cantonese can be very earthy, which is how I feel about a lot of Cantonese music.

My family lived in Chinatown, the seven-block ghetto. At that time it was from Sacramento street--which, by the way, in Chinese, wasn=t ASacramento@ street; it was called AChinese People@ street--Chinatown started from that point to Broadway; didn=t even go to Vallejo. That was the seven-block area. Everybody knew everybody on a first name basis, because it was so small.

My father was a grocer in Chinatown and very prominent in Chinatown politics. He was an official of the Chinese Six Companies, which is still one of the formal organizations that work with Chinese in America. Because of that we were steeped in Chinese culture. My father was also a great scholar, a poet and historian. His family came from journalists. My great-grandfather was one of the founders of the first Chinese language newspapers in America, the Young China Daily, which was supported by China=s own AGeorge Washington,@ Mr. Sun Yet-sen, the first president of China after the overthrow of the Manchu Dynasty. If communism had not taken place, he would have been a high official in Chiang Kai Chek=s government because he was a personal friend of Chiang Kai Chek. He became a state senator from overseas to Taiwan. So that=s part of my fascination and my sister=s fascination with China. Especially because we thought we=d never set foot in it.

My mother was imprisoned in Angel Island. In fact, my mother originally was not allowed to step foot in America because my great-grandfather would not pay a bribe. They sent her back to China on the pretense she had worms. She sailed here and had to sail back. She came a second time; she was only allowed into America the second time. She came over with my older sister, Sarah. She was born in Shanghai. The two of them were at Angel Island together for months before they were allowed here.

We always spoke Chinese at home and English because it was something we had to do. Shirley and I had older siblings and all of us had to go to Chinese language school after public school. My father wanted much more for us. He hired a calligrapher to come to our house and teach us how to use the Chinese brush. Our mother taught us the same ten poems for ten years. She wanted us to have culture so we learned ten poems from the Tang Dynasty; there are 300 of them that are printed. So our culture is not just music. It=s reading. It=s poetry. It=s calligraphy.

Eventually we did visit China, right after my father passed away. He was a renowned poet. The same year my father died, he had visited Taiwan and had been honored there. He was one of the founders of the main university in Taiwan and had always been a heavy contributor to causes like that. Well, he had written a poem about the visit and what it meant to him. After he died, we all went to Taiwan as a family to present this poem to the university. We then went to the mainland to pay honor to my parents= villages. We went to my father=s village first, which is the same village of Sun Yet-sen. After we paid homage there, we went to my mother=s. It was all in the Guangdong province. That was our first and last visit to China.

WBR: That provides a glimpse into the Cantonese side of your Abilingualism.@ How do you get to the other side?

WONG: You have to realize that certain seeds were being planted. It was not our decision. At night, my mother had Chinese music. Every night. During the day, my father had European classical music on. Every day. So during the day we did European music and at night we did Chinese music. And to us it was natural: AEverybody does this.@

My sister and I started learning piano at seven years old. It was a prestige thing in those days. And we were recognized as sort of like prodigies. We started with a Chinatown piano teacher whose daughter was a genuine child prodigy. She taught us until at some point she said, AI can no longer teach you. I have to bring you to this Russian teacher.@ His name was Lev Shorr and her daughter was studying with him. But we were so ghetto oriented. . . . It was outrageous: how she talked my father into letting the two of us leave Chinatown. We were scared to death. She literally had to put us on the bus, one on each side of her, to take us to Sutter Street, which is at the end of the Stockton tunnel. We couldn=t even find our way out of the Stockton tunnel.

But we got to the Russian teacher=s studio. We were too young to realize what we had. Lev Shorr was the Symphony pianist and a classmate of Sergei Prokofiev, who he studied with in the Petrograd Conservatory. He fell in love with us because we were so cute: pigtails, the whole trip. By that time our first teacher had taught us to play AStars and Stipes Forever@ as a duet. We played that for him and he just got such a kick out of us that he took us on immediately.

He also used to listen to Chinese music. Lev Shorr. Now for God=s sake!, what was he doing listening to Chinese music? You have to see the loop of this thing! It=s not linear. He got a kick out of telling us, AI love that music.@ I think it was aired over KPFA, of all things.

My brother Zeppelin--he was named after Graf Zeppelin--was going to Stanford at the time. He adored the violin and played in the Stanford orchestra. So he was very influential and brought Shirley and me to hear Artur Rubinstein and the Pops concert with our first piano teacher, Mrs. Eva Chan. I also developed a great love for jazz because my older sister, Sarah, was steeped in jazz. So we had Chinese music and western classical music in our ear as well as jazz, which was pop music at the time; Rosemary Clooney.

So ask us what our music is and I have to tell you I can=t tell the difference. Later, Shirley and I got our bachelor=s at Mills College. Mills had some of the great teachers of the time, such as Darius Milhaud, one of the most influential French composers of our century. My twin sister Shirley ended up majoring in harpsichord and got her master=s in it. I ended up majoring in composition and got my master=s in it.

I have to mention another musician who=s been such a great influence in my life. Her name is Pauline Oliveros. She is recognized as one of the major composers in the world. And she used to give incredible theatrical productions. She was a composer who once did a theater production that involved the reproduction of the celestial sky. And she did it with little Christmas lights. She was a major force in the beginning of electronic music. And when she did a musical production, it wasn=t just sounds. I was a student in graduate school and I saw all this and it was like Christmas. Pauline told me once that if you want to be successful in your endeavors, you have to learn how to do everything yourself. And so what I did was I gathered around me all the graduate students I could find who would do my kind of theater thing. And I got really facile about involving people in large groups.

WBR: China=s a big place. Was the Chinese music you identified with from a particular region of China?

WONG: The kind of Chinese music we knew in those days was totally from the southern area, the Cantonese speaking people of Guangdong Province. And I would say that the first thing that gives the music its distinctiveness is the instruments. The hammered dulcimer, the yang qin. If you look at, say, every 50 Chinese homes in America, one will have yang qin in the basement. Literally. Because immigrants brought over the yang qin.

Also there is a nasal quality that comes with Chinese music, with the bowed and even the blown instruments. It=s very particular to Chinese sound; not only southern. North and south, Chinese musicians tend to have their Asacred@ repertoire and they=re always reprising it over and over and over. But there=s so much more, with the minorities.

WBR: Where along the line do you begin to transit from being solely a student to performing?

WONG: That began in 1971. My sister and I were not brilliant students of Chinese culture despite our parents= efforts, but all that changed when in 1971 we discovered Chinese music. We had just finished 2 2 years of graduate work in music, so discovering our roots through Chinese music came easily. We took a grand detour from the previous 20 years of European musical training and spent the next ten years steeped in the music of our parents, Guangdong music in particular.

Shirley and I both had been in graduate school at U.C. San Diego at the time and were still steeped in Euro-centric music. We were coming home for summer vacation and my brother Zeppelin said, AYou know the Chinese Cultural Center is giving an eight-week workshop in Chinese music, why don=t you try it out?@

Well, by God, we did. We walked into this little old, black, back-lit, incense-filled Buddhist temple in an alley. That was a real stroke of genius, to start people off in Chinese music in a place like that. I don=t care if you=re Chinese, you don=t walk into a place like that. And here it was, this guy, David Liang, and his father. His father is a very great Chinese musician, very revered in Taiwan. David Liang was our teacher. He spoke perfect English and was doing a lot of research in western music.

We couldn=t believe it! This was the music we had always heard in the movies. You mean, we can learn to play this stuff? My first instrument was the guzheng, which is the one that looks like a koto. I still perform on it a lot. Shirley=s first instrument--=cause we did everything together--was the Chinese mouth organ, the sheng. And between those two instruments, we thought like we were holding on to relics, stuff you find in tombs. Because you do find them in tombs, from the Han Dynasty. Now we were holding these things, playing them. We were transported to a land that we had only heard of.

We were locked in there every day for eight weeks. Then shock: What do you mean its over? We had just gotten started. So we formed a group immediately under the name Flowing Stream Ensemble. We started meeting at my father=s store. The amazing this was that among us there were only two people who knew any Chinese music. They had studied at UCLA as graduate students. They were our historians; the ones who beefed up what we didn=t know. When the Flowing Stream Ensemble started giving concerts, they were the ones who played the main body of these concerts. Shirley and I played the only piece we knew. The only reason we had the audacity to do that was because we were graduate students and we felt like we knew the music.

The Flowing Stream Ensemble performed its first official concert at the Music and Arts Institute in San Francisco in 1972. It was sponsored by the Artists Embassy International, the first organization to bring Ravi Shankar to America. Their founder has passed away, but they=re still very strong. We were playing exactly at the moment when Nixon landed in China. We had a television and when Nixon stepped out of the airplane, we stopped all proceedings and played a piece called AOpen The Gates@ to commemorate that. It was quite theatrical.

WBR: At the time, were there other traditional music ensembles in Chinatown?

WONG: Yes, the Abasement clubs.@ My father once said to us: ADon=t you go near those basement clubs.@ Because he was hinting that there were some real sleazy characters down there and that they all gambled. Of course they did. Mahjong was the favorite pastime. We didn=t know that whole families visited the basement clubs. There was one club two doors from my father=s grocery store. We used to try to look down there.

What it meant was that they were like lower; you had to go from the street down the stairs. Well, they had basement clubs down there that were social clubs that were meant for Chinese immigrants who kept to themselves and who needed a place to hang out. You=d pay dues and get a key probably. And there=s maybe be a little kitchen, a mahjong table, and newspapers. And it was like family. You didn=t have to be a musician, but they incorporated music as part of their pastime. There was always music going on.

But the way the basement clubs were like, you didn=t have to know anything about music, so it wasn=t daunting like that, and they would pass on what they knew to the younger kids, who were enticed to learn it. That was how the tradition was passed on. So they kept it as a kind of family, and this is true of many cultures, of course; the Irish for instance. So it was mixed up with all the other things that Chinese love to do, which is eat, gamble, read newspapers, converse, listen to music. All this would be going on at the same time. There was nothing formal about it. Every once in a while, musicians would be asked to do a function. Then they would sort of throw together a more serious rehearsal.

The truth is some of them were not in the basement. As it happens, there is another very famous basement club on Waverly Place, which is the alley with the most history, at least the most written up one. The club is upstairs; you have to climb up three or four flights. You know the best time to go to Chinatown to catch the flavor by standing there and listening?: July 4. A lot of these clubs use July 4 for their founding date. So on July 4 you hear Chinese music pouring out of upstairs or downstairs.

We copped our first music director from the basement clubs that was in the basement at Portsmouth Square. His English name is Leo Lew. The guy was the real deal. From China. Learned as a kid. The whole oral tradition. This music was in his every pore. We hung out with him for years. It all started in his basement club. He saw that we were really serious. He knew that his basement club music was just another side of their social scene. He was always having to wait until everybody was through with their mahjong playing, eating, conversing, reading newspapers, and then they might play some tunes. He got tired of it and became our music director.

That was a coup. That=s when the Flowing Steam started taking off. We started playing in venues that at that time hadn=t been open to Chinese music. We played at every museum in town. We started playing universities. We started moving out to territories where classical music is usually played. Old First Church.

We got into a folk festival at Fort Cronkite where we got to know these Irish musicians. They listened to our music and said, my God, we sound like them and they soun like us. And we holed up in a cafeteria and played for each other. What happened was that it was very funky, very folksy. We tried picking up their stuff and they tried picking up our stuff and it was amazing. Kind of a jam session. So that=s how we got out there and got known. The Flowing Stream Ensemble was probably the most visible Chinese music ensemble outside of Chinatown.

WBR: Do the basement club ensembles continue?

WONG: Oh my God, yes, and they are distinguished between the northern style, so they=re Mandarin speaking, or the southern style, so they=re Cantonese speaking. But some provinces in southern China aren=t Cantonese. There are fishing villages, for instance, that have a whole different kind of music, and a whole different dialect and even a different kind of eating.

WBR: Was the Flowing Stream comprised only of students from this eight-week class?

WONG: No. That=s another great story, how we met Noel Jewkes and Bill Douglass. We were walking around Chinatown. At that time we were living upstairs above my father=s Chinatown grocery store, right on Stockton street between Broadway and Pacific. We were walking up upper Grant and we went and hung out at this thrift shop and this guy walks in and he=s got bamboo flutes in this archery leather bag. We said, oh, you play bamboo flutes. And he looked at us and said, well kind of, I=m a jazz musician, you know, I=m learning how to play from my bass teacher, but I don=t know a thing about Chinese music. We said, AOh, we=re just forming an ensemble.@

This is 1971. Summer=s coming to an end. We only have a handful of players. He said, AOh, can I bring my friend Noel?@ We said yes and for the next six or seven years, the Flowing Stream survived on great flute playing by Anglos. Because of that introduction, Bill Douglass is now one of the premier players of bamboo flutes in the music industry, because his friend Mark Isham, a great soundtrack composer, always uses Bill. He=s in a lot of major commercial films, Wayne Wang films. If you listen to Black Stallion, Never Cry Wolf, his work is on the soundtrack.

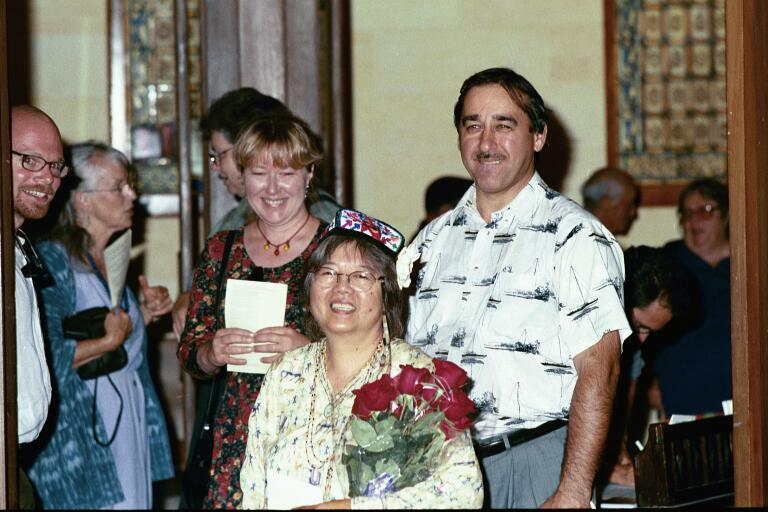

Betty Wong's Phoenix Stream Ensemble, formed to practice

the art of collaboration between musical styles.

WBR: With so much success, why the need for Phoenix Spring?

WONG: I formed a separate Phoenix Spring Ensemble in 1977 because I wanted to branch out. The musicians in Flowing Stream had such a depth of musical styles that we were not tapping into. We were staying with traditional music, always, although we allowed a few western instruments into it. The Phoenix Spring Ensemble was formed to practice the art of collaboration between musical styles and cultures. The Ensemble is gifted in musical resources as its members are proficient in European classical styles, in American jazz improvisation, in extended instrumental techniques, and can incorporate conceptual approaches in composition as well.

I also have my background in jazz, although it=s as a composer. You see, I can=t improvise worth a damn. I am so solidly trained as a classical musician that all I can do is compose. All the jazz licks and jazz parts on the piano are composed. But it works. While I was studying jazz, my teacher asked, AYou know what, you ever thought of doing the McCoy Tyner kind of arrangements? He=s really into fourths and fifths. And you know what was amazing was that overnight I composed a la McCoy Tyner and it came out of me just like that. I couldn=t believe it. I played at the Asian-American jazz festival, which was one of the highlights of my career. And Jon Jang comes up to me and says, AMcCoy Tyner.@ That absolutely confirmed to me that it really happened; it wasn=t my imagination. When somebody who is a jazz musician comes up and says AMcCoy Tyner,@ he recognizes a connection.

Because of the backgrounds of my musicians, I think Phoenix Spring gives them a chance to have their first collaboration of their whole being. So it=s kind of like the music is what holds us all together. At the same time, the Phoenix Spring Ensemble is not a fixed body of musicians. It=s any musician who responds to my projects and will come forward and play my pieces. The Phoenix Spring Ensemble basically exists to play my pieces.

In a way, I wanted an ensemble that reflected my experience in summer of 1974 with the Center for World Music, which was very instrumental in a lot of people=s lives, in my life, in Paul Dresher=s life, in Mimi Spencer=s life. For that one summer, the Center took over the Julian Morgan Theater in Berkeley. It was in that building and in every room, every nook and every cranny that there was a class going on, seven days a week taught by masters brought in by the Center. We could literally stay there from morning until night and, if we had the stamina, we could go from class to class all for one tuition. One of the classes was kanjira, a South India tambourine, something like a talking drum. The thing about the kanjira is that it=s made from skin taken from the tummy of a lizard. So to warm up the drum, you literally have to rub the lizard=s tummy. The class really changed me. I had always had some rhythm problems that I couldn=t fix. I didn=t have the rhythmic integrity I wanted. It just kept escaping me. But that summer, I started learning hand drumming. It was almost 30 years from the day I started piano lessons that I discovered the answer to how you fix your rhythm. You drum so that you=re doing nothing but. What an experience!

There were a lot of problems studying with these masters at the Center for World Music. People who maybe this was their first trip to America. They were shocked by us and we were shocked by them. They had a tradition of teaching and not everybody who came to those lessons was aware of the tradition. The teachers expected a certain kind of behavior and respect and they were treated with great awe and respect.

But there were certain cultural things. You were expected to serve your teacher. You were expected to address them in a certain way. You were expected not to be too pushy. And in some cases the whole idea of taking notes and recording was just shocking. They didn=t teach that way. It was oral tradition.

I arrived at the Center after my first experience in Asia, which was not in China, but in India, New Delhi, earlier in 1974. Suddenly my priorities shifted and I became totally immersed in Hindustani music. I have a lot of tapes; thank God the tape recorder was invented. We used to have all-nighters. We=d bring these huge reel-to-reel machines and all night long we would be dubbing for each other. We were just eating and sleeping the stuff. I was still leading the Flowing Stream Ensemble, performing traditional Chinese music, but my ears were taking in many, many new experiences from Chinese music to Indian music to Javanese music to Japanese music--all being offered simultaneously. The building virtually rocked with sounds of Asia from morning to night seven days a week for the entire summer of 1974.

Meeting every day is exactly the traditional way. And the thing that was so awesome about the Center for World Music is, yes, we met every day. That leads me back to the statement that if you really want to learn this: that=s what you have to do: immerse yourself. When I first started studying world music, I studied sitar for seven years. The Indians said, you really want to know our music?, ok, you start eating our food, you start spending all your time with us, you start dressing like us. You can=t just play the music.

That is so true. Shirley and I teach Chinese music at the Community Music Center. We started in 1973 and to this day we have never had a break. I will now say; the whole idea of Shirley and I teaching Chinese music, we=ve become very, very protective of the culture. When it came to Chinese music, we did not want students to come to us and say, hey, Ateach me how to hold this instrument.@ ATeach me how to play a couple of scales.@ AI have an idea.@ AI want to improv on this.@ AWe want to go back and jam.@ And we=d look at them and say, hey, you want to study our way you take the whole nine yards: you learn tradition, you learn the history; you learn the pieces written for this instrument. And that=s how you=re going to learn from us.

Through that we=ve kept this thing on the up and up. It=s kind of been an extension of ourselves. We keep to the music, to the mainland, to the community. And that=s how we do it. And from the beginning, we embraced the community. Remember the fall of the International Hotel? We were there playing for that. We did a gig playing the opening of the Chinese Cultural Center; all that kind of thing.

So we represent a different history than a lot of the mainland virtuosos who are here now. The difference is that we can=t compete with them in terms of how well they play. But we have a broader spectrum of Chinese music that they do.

Anyway, when I formed the Phoenix Spring Ensemble, which, by the way, is named after my mother=s name. It was in her memory that I formed the Ensemble, that we have a philosophy about this Ensemble. We want to perform in places where we transform the space. We=re not necessarily into concert hall space. We want to involve people who listen to this music and it=s almost like spontaneous combustion when listening to Xinjiang music. You can=t help moving. You can=t help listening. Because with the kind of music I feel so strong about, there is no AYou are playing; I am listening.@ It gets so involved. It=s a passion with me, as you can see.

And I=ll tell you the word: Xinjiang. I have gotten these guys to play Xinjiang music were they never introduced it into their repertoire . . .

WBR: But wait. How did Xinjiang music ever come to your attention in the first place?

WONG: Winston Wu, one of the founding members of the Flowing Stream Ensemble. He was fanatic and he was a natural. Everything he picked up he could play. But his mind-set: he was just like everywhere. And he was never in one place very long. And he was very daring: AOh I can play this instrument; would you like me to play this at your concert?@ And none of us would know how to play it, so we=d say, AGo ahead.@ It was amazing.

And one day he plays this cassette. Xinjiang music, from Northwestern China; my God. First, it=s not at all the pentatonic scale. It=s got any Arabic sound to it; what=s that? Then it=s got this rhythm: 7/8. It was a first taste of non-conventional meters. We played that cassette to death. We got the music off the record. We started transcribing it in number system--the Chinese notation system is a number system.

One of the reasons why I think that the Phoenix Spring has had such success is because even though I=ve had many responsibilities for all its projects, the rehearsals are often communal. Mary Ellen Donald, especially, because her listening is 100 percent. She=ll say I think you need this here, I think you need that there. She=s always professional. Are you sure you don=t want me to use this drum? How about this other drum? Our sax players, Eric Crystal and Ken Rosen, being supreme jazz musicians, were adept at Islamic Chinese music of Xinjiang. It helped that Ken did a very steep gig in Klezmer. There some similarity between Klezmer and Xinjiang, because Xinjiang is basically Middle Eastern music, even though Xinjiang is in a different part of the world geographically. So it was like that, working and working and getting feedback. Always having respect for the original material. And I didn=t want to erode into the natural flow of how the music has to sound. So what I leaned on instead is virtuosity.

But my teacher, Mr. Lew, said: AI refuse to play this music, this isn=t Chinese music.@ I said, AWhat do you mean it=s not Chinese music?@ Winston says it=s Chinese music. Look at the record. It says it=s from China.

Well damn if Mr. Lew wasn=t right. It isn=t Chinese music. It is the music of Islamic China. Today the Chinese incorporate every music, even Tibetan, as national music. They consider it Chinese music. But to the Uyghar, of course, it=s not Chinese music. It=s their music. But I didn=t know it at the time. So I had the nerve to tell my teacher, AWell, you don=t have to play if you don=t want. We=re going to play it. We love it.@ And he never played it.

WBR: The Uyghur?

WONG: The Uyghur are the main body of people who live in Xinjiang. I have embraced the history of these people, which goes back to the ancient Silk Road. However, I began to realize that Xinjiang music meant more than the folk music of the Uyghurs. After some study, I realized that some of the music we play rightfully originates from Tadjikistan and Kazakhstan as well. So when we did this cd, I didn=t want to stop in Xinjiang because I wanted to trace the other influences from across the Soviet border, the music of the Tadjiks and the Kazakhs. So our description of our offerings as a Adreamfield of American Eurasian nomadic music@ extends throughout Central Asia.

This is, of course, the terrain that Marco Polo lived in for years when he was serving the Kubla Khan, but the Silk Road predates Marco Polo by centuries. At the time of the Tang Dynasty, or even before, China embraced musical representatives from Central Asia, especially Persia. Do you know that most Chinese instruments are Persian in origin? So are most of the Chinese instruments played on the cd. This is the whole trading of the Silk Road that people don=t really pay attention to. It was a trading of cultures, of religions. It was how Buddhism came into China. Forget the merchants! What about the monks? What about the philosophers? What about the historians? So we=re talking about an exchange that was much greater than commerce.

WBR: How does Mary Ellen Donald come into the picture?

WONG: That began with getting a commission from the American Conservatory Theater to provide original music for a production of Eugene O=Neill=s Marco Millions. And Eugene O=Neill is very specific about what kind of music he wanted, when it should come in, where it should come from. And he mentioned the Tartars. It was the era of Kubla Khan and Marco Polo.

I had been a teacher at the Community Music Center since 1973. A member of the Community Music Center=s board of directors knew me and knew about my interest and my teaching of Chinese music. And she was friends with the play=s director, the director of the play, Joy Carlin; she=s a director of ACT. In conversation I guess Joy said we=re looking for a musician who has the historical knowledge, the people to play, the library. Well, I had it all. By that time, 1988, I was steeped in Xinjiang music. I had been doing it for 10 years. I knew exactly what music I wanted to provide. And I knew I needed a drummer.

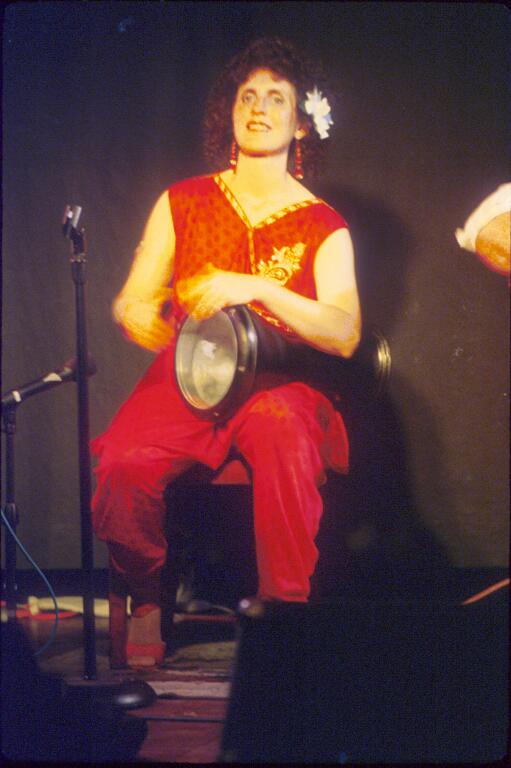

Mary Ellen Donald

Mimi Spencer

Now, what also was happening is that I had been studying recorder for some

years. Recorder music goes to Sephardic music and reflects Moorish-Asian

influence in Spain. So Spanish Renaissance music, believe it or not, uses frame

drums. I was studying recorder with a member of Ensemble Alcatraz, which was

really into Spanish Renaissance music. Their drummer was Peter Maund. Fabulous,

fabulous drummer. But he wasn=t

available for ACT. He said, AWhy don=t

you call up my teacher, Mary Ellen Donald?@

Now, what also was happening is that I had been studying recorder for some

years. Recorder music goes to Sephardic music and reflects Moorish-Asian

influence in Spain. So Spanish Renaissance music, believe it or not, uses frame

drums. I was studying recorder with a member of Ensemble Alcatraz, which was

really into Spanish Renaissance music. Their drummer was Peter Maund. Fabulous,

fabulous drummer. But he wasn=t

available for ACT. He said, AWhy don=t

you call up my teacher, Mary Ellen Donald?@

And that=s when I met Mary Ellen Donald. And Mary Ellen Donald, she just opened up an incredible world. That=s what started it. And that year we started going to Mary Ellen=s extravagant ATreasures of the Middle East@ that she produced once a year at Lone Mountain college. These were hours of belly dancing and this, that and the other thing. You want to talk about other producers of great extravaganzas, you=re talking about Mary Ellen Donald. So between the two of us, we just hit it off. And you can imagine, it was like Barnum and Bailey. We both knew exactly what it took.

With Mary Ellen, I got Mimi Spencer also. I never had Mimi play with me, ever, even though I knew her through the Center for World Music. She was there that same summer I was. Mimi is the foremost improvisational artist I know, one who could take Xinjiang music and bring to it her knowledge of Greek and Turkish and Egyptian music.

WBR: And Mary Ellen was your connection to Mimi?

WONG: Absolutely! Because they=re partners. Those two have been playing together forever. At the Amira Restaurant, at the Grape Leaf restaurant, at all the different Egyptian/Arabic festivals. As far as I=m concerned, they are like two peas in a pod. You don=t think of one without the other. So when you get these two partnerships going on, how can you lose?

So Mary Ellen Donald came from the ACT gig in 1988. And she was just a natural. And, with me, she basically only does Xinjiang music because it goes so beautifully into her Arabic training. I don=t have to ask her to stretch anything beyond what she already knows what to do. And along with her comes this whole array of percussion.

WBR: How does this come together with In Xinjiang Time?

WONG: By staying on the Silk Road. My first concern is creating this cd was to extend the utmost respect for the original Xinjiang material. I really loved the idea of preserving, as much as possible, the original inspiration. Having no access to indigenous instruments from the region, I chose traditional Chinese instruments, which had originally been imported from Central Asia thousands of years ago. But we couldn=t duplicate the original sound, so what we did was add our own instrumentation and our artistic sensibilities. Our version of Xinjiang music results basically from a group effort.

But on the Silk Road, which is a state of mind as well as a historical and geographic entity, Islamic Chinese music could be played; classical Chinese music could be played; Arabic music could be played. So I have musicians playing real music from Xinjiang or Chinese or American compositions inspired by Xinjiang culture. I have also gotten musicians who have recently emigrated from China to play Xinjiang music, which they had never before introduced into their repertoire on a regular basis.

The Phoenix Spring Ensemble brought its base of musicians trained in European, Arabic and jazz to create the American and contemporary arrangements and compositions. We also worked with the tradition-based Melody of China Ensemble, which I met through my own Chinese teacher, Ms. Liu Weishan, who is a very great teacher. Four pieces on the cd originated in 1988 with ACT=s Marco Millions production. Two of my own compositions are only the release. All the improvisations on AKanun,@ one of the selections on In Xinjiang Time, is pure Mimi and not steeped in any Central Asian tradition. There are pipa performances--pipa is a Chinese pear-shaped lute which is one of, if not the, supreme instrument of Chinese music--and Mary Ellen Donald provides percussion on all of them. On the last cut of the cd, AXinjiang Scintillating,@ drummer Anthony Brown overdubbed to intensify the jazz elements of the piece.

Wang Hong and Zhao Yangqin are founding members

of the Bay Area's Melody of China Ensemble

And now the reason why I credit the Melody of China Ensemble is that there

are pieces that I=m not responsible

for. And those are pieces that belong to the soloist=s

repertoire. And when you see that it says Melody of China, it=s

their piece.

And now the reason why I credit the Melody of China Ensemble is that there

are pieces that I=m not responsible

for. And those are pieces that belong to the soloist=s

repertoire. And when you see that it says Melody of China, it=s

their piece.

But I=ll tell you right now. Being a minority in the western world, I=m very sensitive to the struggle for keeping a culture intact. Xinjiang means Anew dominion.@ It is not their own term for themselves. I will not flinch at all saying that I am for Xinjiang independence. Their situation in Xinjiang is not that different from Tibet. I believe that our cd, In Xinjiang Time, is the first saying, AXinjiang exists; Xinjiang deserves to be recognized, deserves to be heard.@