Essay

There are two essays to be written for this class. The only three differences between them are:

- The first essay may or may not receive a grade, but in any event that grade is not part of the final, course grade calculations.

- The first essay is when we give you considerable feedback on your work. The grade on the second essay is the grade for the Grade Category "Essay" which is a substantial percent of your final course grade.

- The first essay covers material up through the first portions of the class. The second essay covers material from any portion of the class except that it cannot be a repeat of the topic of the first essay.

- The first essay is due near the middle of the term. The second essay is due near the end of the term.

- We will not be checking whether the first essay meets good academic honesty standards. There are severe penalties for not doing so. We design the submission of the second essay in a way that it is difficult to submit work that is not yours. If you are a non-native speaker, I suggest you read my policy on that found at CROSS-COURSE (click on the button on the Announcements/Start Page).

Below are extensive comments and instructions. While it might seem like a lot, the specificity is because this is a teaching module on writing a good academic essay. If you are already a strong writer of essays, perhaps my comments will help fine-tune your writing skills. If you are early in the stages of writing a college-level humanities academic essay, perhaps this module will provide some guidance.

Please read this module keeping in mind the basic assignment:

Write a credible and interesting analytic essay of about 1800-2400 words, on a well-focused topic relevant to the content of this course. Turn it in on time and in good form.

To accomplish this you will do research and read the ideas of others, while writing and re-writing your essay. I expect the essay to be the result of some thoughtful time not a quickly written affair, and certainly not a first draft. I very much hope that you will enjoy exploring a topic as well as polishing your writing skills.

The below should help you understand what I mean by "credible", "interesting" "well-focused" and "good form" and will tell you how to "turn it in". You should also consult the Key Concept & Terms page since those general comments about my expectations for essays whether as a paper or on an exam are relevant.

I have developed a one-page PDF that presents what I see as the basic parts of an academic essay and their relationships. It includes a grading rubric. It should give you a good sense of where you should set your writing goals. Go here: The working parts of an essay.

Overview

• length

• how to submit

• academic honesty

• basic essay goal

It should be APPROXIMATELY in the 1800-2400 word range, but effective length is determined by the essay goals and the expressive style of the student (some use concise language, others are not — please be concise where possible). There is no real correlation between word length and grade: accomplish the goals of the essay with prose that has been tightened by a rewriting.

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

— William Strunk Jr. in Elements of Style

Reading Strunk fundamentally changed my approach to writing. He convinced me that it is the responsibility of the writer, not the reader, to resolve clarity issues, including concise expression where appropriate. Please rewrite your essay to improve its clarity, organization, and conciseness. Ask yourself whether that word(s) is needed: "in approaching this subject I would like to suggest that we need to reconsider whether giri-ninjo is central to the play" could better be written as "I will suggest that giri-ninjo is not central to the play." Note these resources:

Anonymous. "Writing Concise Sentences." Web. 21 Nov 2012. http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/concise.htm.

Weber, Ryan and Nick Hurm. "Conciseness." Purdue OWL. Web. 21 Nov 2012. http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/747/08/.

Also, please do not take us on a journey as you "think aloud," writing your way towards a conclusion.

The essay has specific style requirements. See below.

It is submitted electronically, with severe late penalties. How to submit:

*If there is the option to submit a draft before the official ESSAY TWO deadline, follow exactly the submission guidelines below for ESSAY TWO except that both file a) both the subject line and file title should be J7AFa13 LASTNAME classname ESS02 earlydft, b) there is no need for scanned material that supports your cited sources, and c) there is no need, of course, for the additional copy of your essay that would have only your codename, not real name.

- File Formats — You will be submitting digital version(s) of your essay.

ESSAY ONE: You must use MSWord .doc or .docx as the file type. (This is because we use the comments feature of MSWord to send you our feedback.)

ESSAY TWO: You may use MSWord .doc, MSWord .docx or PDF. Make sure that your footnotes are visible. For the accompanying scans, if any, you may use JPEG, PNG or PDF. - File titles —

ESSAY ONE: J7AFa13 LASTNAME classname ESS01

ESSAY TWO (for the essay itself): J7AFa13 LASTNAME classname ESS02

ESSAY TWO (for the essay itself, anonymous version *see below): J7AFa13 codename ESS02

ESSAY TWO (any scans that are part of your submission): Title it like this author - short title - page; so, for example, Ueda - Interpreters - 22-25.

*If, as a native speaker, you are submitting the original plus and edited version, indicate this in the title by adding at the end ORIGINAL-VER and EDIT-VER.

- Send it as an attachment(s) to an email. We separate the submission from the email (and never go back to the email) so if there is something important you want to say or ask, put it INSIDE the document, at the top, not in the email.

Send ESSAY TWO in two forms, in the same email. The first form is the usual essay, with your name on it. The second is exactly the same essay but you have removed your name from inside the essay and from the document file name. The first has a file title with your name on it; the second has a file title with a codename you have invented. I make a record of the pair (they arrive at the same time, one with your name and one with the codename, so I am able to create a list), then I separate the sets and distribute to the second reader(s). They will grade your essay purely for its credibility and interest, reading through it just once, in 5-15 minutes. They do not know who you are and you do not know who the grader is. (Obviously in semesters where I have only one GSI some of this is not true—you will know who was the second grader.)

ESSAY TWO attachments: If you have any scans of sources, they also go into this email. PLEASE SCAN INTELLIGENTLY AND KEEP FILE SIZES SMALL: scan only what you need, send us only what we need, and keep scan quality readable but not ridiculously large. - SUBMIT ON TIME! I do not offer extensions except for extreme situations.

- Destination of the email — Send it to me, Wallace. If your mentor is the GSI, send it ALSO to him or her using that same email by putting his or her address on the "To" not "Cc" line. Do NOT send two separate emails.

ESSAY TWO: Send it only to me, Wallace. I will distribute to the GSIs once it has been OKed. - Submission rejections and bounce-backs — You have NOT submitted until I have received from you an open-able, non-corrupt, document. I am, in other words, the gateway for submission. If I OK your document, then I give the OK to the GSI to begin working on it. If you send something I can't open, or use another file type, it is likely you will receive late penalties. Of course you cannot work on the essay any further after you have submitted, even if bounced back, except for the changes I specify. "Fixing" your essay, even a little, after the initial submission will definitely incur full late penalties and might be considered academic dishonesty. Also, avoid double submissions. Before submitting make sure you are ready to submit.

- Subject line —

ESSAY ONE: J7AFa13 LASTNAME classname ESS01

ESSAY TWO (for the essay itself): J7AFa13 LASTNAME classname ESS02

Academic honesty is important. Be sure you understand the "context is king" and "fair & accurate representation / over-the-shoulder" and "no forgiveness" rules as described on my Academic Honesty Web page. Do not have others edit or otherwise contribute to your essay, including outside reading for improvement. If you do have editing or other advice, submit an original and the edited version. The original will need to be submitted early (see details below). The original will be graded, the edited version will be referred to if your meaning is unclear.

The basic goal of the essay is a credible, interesting and well-focused exploration, elucidation and/or interpretation (in other words, "analysis") of a cultural entity using, if possible and useful, a course concept (such as kotoba-kokoro) or extensions from them.

"Entities" can be texts of some sort, or concepts such as "mappo" or "sabi", for example. This class covers literature and culture. If your essay would be appropriate to a history, sociology, anthropology, political science, etc., course it is not right for this class. Rethink things.

Using course concepts: there is no plus to using a course concept if it wasn't helpful, there is a slight minus if you force the use of a concept when it clearly isn't fitting well with the topic, and there is a grade minus for not using a course concept with a specific topic when it is clear that would have been a better path than the one you took.

Basic procedures

• getting a topic and mentor

• note for non-native speakers

I will assign a general topic. (See list at the end of this document.) You need to find a specific topic within it or you can simply go your own way with a different topic. You might want to run the idea past your mentor first, however. Specificity is an essential element of good essays. "About the tea ceremony" is a terrible essay idea for this class. "About Korean influences on the tea ceremony" is specific and immediately interesting. "Sumo in early Japan" — nope. "Sumo's use of nawa and its Shinto implication" — much more promising. The basic rule of thumb: avoid at all costs the "About [general topic]". Take us on an adventure to something specific. You cannot create a specific topic just by thinking. You will need to do a little research, think, do some more research, and so on, working you way to an excellent, specific topic. (You might consider looking over the section below where I comment on the quality of various titles. It gives a good sense of topics, too.)

Topic list Fall 2013 You will be assigned a number that corresponds to a topic. However, you can propose a different topic. These are the general areas—you must find something specific within it. Specificity is important.

- Haiku, concepts behind haiku, haiku poets, haiga composed between 1600-1850

- Heian period nikki but including the Pillow Book and Confessions of Lady Nijō (which is later but in the style of Heian period words)

- Nara period texts: Kojiki, Nihon shoki or any other literary prose written before 750

- Recluse literature

- Renga before 1700 (for Essay Two, renga before 1868)

- Things associated with the imperial poem anthologies such as the Kokinshū or Shin Kokinshū

- Things associated with the Man'yōshū

- Uta-monogatari written before 1100

- Any example explored with care of the impact of Buddhism on an art form

- Something in the arts related to the Tale of Heike

- Something in the arts related to Northern Hills culture

- Something in the arts related to Eastern Hills culture (if it is listed on the PDF outlining the basics of Northern Hills and Eastern Hills culture it is acceptable, other things might also be acceptable)

- Something in the arts related to Genroku culture including but not limited to Matsuo Bashō, Ihara Saikaku and Chikamatsu Monzaemon

*You are welcome to try Tale of Genji but proceed with care.

You will have a mentor. Work only with your mentor on the essay unless you are having a problem with your mentor. Then you can contact me.

We will give you advice on ideas you bring to us but we will not give you ideas or advance your ideas.

We will give you schematic suggestions on how to research but we will not give you article or book suggestions.

To the extent possible use office hours, not emails, to ask questions. That means planning ahead. This isn't a hard and fast rule but, in general, it is better to talk than exchange emails.

If you are a non-native speaker you must write the essay yourself, with no editing help. If you are concerned we cannot follow your English, you can submit a second essay that is edited. You need to identify who edited it, when, and how much editing. You will be graded on the essay you wrote, we will use the edited essay only to help clarify a point where necessary. Not following this rule will be considered academic dishonesty and you will score an "F" and you might be reported to the University. Furthermore, if the individual who helped you is in the class, that student will be considered by me as facilitating academic dishonesty. That student might be reported to the University as well. You will also be asked to write another essay, with at least a portion of it completed in the presence of me of the GSI, in order to pass the class. Therefore, please just submit your work. We will be happy to give you some advice on good English style. You will not be "graded down" because of poor English style as long as it is clear that you are making an effort. We will focus on the concepts.

Position your project on the research – analysis spectrum

Research papers carry out experiments to produce information or gather information, organize and present it. Purely analytic essays offer the writer's idea on how to think about something. Most academic articles are a combination of these: some information is gathered (and information can include what other scholar's have offered as their analysis) and the writer uses this to draw conclusions or offer ways of thinking about something. I request that your essay be positioned towards the analysis spectrum in most cases but I have received some excellent research-intense papers. If you lean towards research it must be high-level, not the basics about the topic. If you lean towards analysis, we as graders understand that you are new to the topic and we will grade leniently on that point. We will be watching more carefully whether you have proceeded in a credible way, and have conveyed something interesting about your topic. It is OK to take some risks in your claims as long as it seems you have given your ideas a good critical evaluation before committing to them.

Advice: Trying to credibly apply one of the frameworks I have offered in class (soto-uchi; kotoba-kokoro) to a literary work, or exploring the role of one of the other concepts (mono no aware, for example) in a literary work sets up an analytic essay approach. Comparing two objects, if it gets beyond "this is how they are the same, this is how they are different" simple outlining, is also an analytic approach. (Read, however, Key Concepts & Terms: compare.)

Below are instructions, advice, and grading comments on all aspects of the essay.

Checklist

Your essay at minimum needs:

- It must follow the above submission guidelines. Please note that ESSAY TWO requirements are different, and more extensive.

- It must be entirely your own work.

- It must in all aspects be academically honest in its content.

- It must have profited from good research.

- It must have an informative title (see below).

- In 99% of the cases it must have a thesis.

- It must use footnotes, not in-line parenthetical citation format.

- It must have a bibliography.

- If it is ESSAY TWO, it must include the special requirements for footnotes and bibliographies as outlined below, and must have accompanying, appropriate scans for the sources it your sources are not digital. See below.

- It must use proper style (MLA or Chicago) throughout, in its basics.

- It must treat book titles and article titles correctly in the body of the essay and elsewhere, in other words: book titles | "article titles".

If any of these components are missing, the essay invites a very low score.

Other requirements set out in this module are highly valued and if they are not present they can degrade a score but they are less serious than the above.

General comments, late penalties, academic dishonesty penalties

I again refer you to a one-page PDF that presents what I see as the basic parts of an academic essay and their relationships. It includes a grading rubric. It should give you a good sense of where you should set your writing goals. Go here: The working parts of an essay.

Your essay must be on time, and must have followed the submission instructions.

*Good essays require time. There is no magic way to make that disappear. However, strong core ideas tend to lead to successful conclusions more quickly than struggling to make an average idea work somehow. So, value the time put into getting the one or two good ideas that will be the heart of the essay.

*Effective writing processes are almost always non-linear: some research, some writing, return for more research, continued writing and rewriting. Formal matters can perhaps be taken care of at the end but allow time. I budget about 30% of my total writing time for all the picky details involved in getting the form correct.

*Time management. There simply must be time to do the above non-linear work (some research, some writing, further research, etc) because this is how you clarify your ideas and an essay without clear ideas is not a finished essay. It is a draft. BUT, besides finally getting to the ideas you really want to say and that you understand well is not the only time intensive portion of the work. You simply must allow time to critically evaluate your work, to organize and polish it to convey your ideas.

If your essay is on time and has been submitted according to instructions, it will be graded on some specific issues with this over-arching question always present: Is the essay credible and interesting?

Grading component that affects the overall score—Timely completion:

- 0-1 hour late, 5% deduction applied, after grading is complete, to each of the three core area scores (research, content, form)

- 1-48 hours late, 30% deduction applied, after grading is complete, to each of the three core area scores

- 48+ hours late, 50% deduction applied, after grading is complete, to each of the three core area scores

- never submitting an acceptable essay, "F" for the course grade, including those who are taking the class P/NP (this grade is not used for the first essay)

Grading component that affects the overall score—Academic honesty:

- Doesn't meet the "over the shoulder rule" (fails in being "fair and accurate"): one full letter grade deduction regardless of the number of times it occurs (A becomes B, B+ becomes C+ etc).

- Plagiarism that is the result of lack of attention (intentional or unintentional, it makes no difference) to "context is king" rule, two full letter grades deduction.

- Other more severe forms of plagiarism and other acts of academic dishonesty (having the paper edited or written by another, purchasing essays, etc), "F" for the course and a report to the University.

Research and your use of it

You will be graded on the judicious selection of resources, and judicious, accurate and honest use of them. "Judicious" means that you have used good judgment in selecting credible, valuable-to-your-topic sources as well as how they have helped improve your essay.

Good ideas are grounded in knowledge, both factual and conceptual. Research of facts gives texture and interest to your work and can help with credibility. However, reading and understanding relevant concepts is the most powerful way to give depth, breadth and sophistication to your work.

What sources you find says a lot about how carefully you have approached your work. Your credibility rests on it. Find excellent sources: you are generally safe if you find articles in academic journal (including online repositories of such journals such as JSTOR and MUSE), or monograms published by academic houses but even there you should make sure the work appears solid.

How you use those resources is equally important. You simply must understand the context of your material. This might require reading a book's introduction, or the full article, and so on. Google Preview and Snippet material is NOT acceptable except when you are simply harvesting a particular fact. Be very careful that you understand the context.

Your essay becomes vastly better with even a few hours spent reading quality sources that offer concepts, ways of thinking, about your topic. Your essay becomes excellent when you can find a way to use those sources in fashioning your essay (and I don't mean quoting from them, I mean using the concepts in them). This takes time. Your goal should be to find one or two high quality works (articles or books or portions of books) on your topic that have concepts relevant to your topic, not summary information alone. You should read them well. That positions you to write effectively, interestingly, and in a time-efficient way.

Suggestion. Get out of the virtual world at some point. DEFINITELY avoid general search engine searches (that is, searches of the whole WWW, not academically-oriented subsets of it). Go to a library for part of your research—it will almost surely be more time efficient and more nurturing to your project. I'm not suggesting that you not use online resources; I am suggesting that you avoid the basic search-engine research approach, which generally provides a scattered view of things, and opt for a good combination of library research or search-engine use that is tied to specifically academic resources.

Content (information, the ideas of others, your ideas)

The body of your essay—the information you offer, the ideas of others you have encountered and conveyed to the reader, your own ideas on how to think about the topic (conclusions, observations, interpretations, speculations)—should be credible and interesting.

Credibility comes not just from the sources you have found and how you have used them, but also from the tone of your essay: it should be even-handed, objective, not salesman-like or strongly rhetorically pushing a point, it should be reasonable in how it offers of balanced, careful claims. ("Reasonable" might mean you have to argue your point, sometimes not but bald assertion is rarely acceptable.) *If the reader feels you have rushed through your thinking, your credibility is dead in the water.

Interest. You need to be interested in your subject, and convey that. You will have less of an uphill battle if you spend some time thinking about what might be interesting to others before you decide your directions. You do not need to be entertain. Offer "food for thought".

Organizing the roll-out of your information and ideas

Good organization includes an orderly and reasonable presentation of your ideas so we can follow easily and can, with little effort, find your main points and distinguish them from your minor points.

Orderly and reasonable presentation is extremely helpful in credibility since we will not puzzle over the steps in your presentation. Sometimes "orderly and reasonable" means "logical"—and you should of course avoid errors in logical argument—but it also means just what works at a common sense level. Therefore, always, always step back and critically evaluate your work to see if it really makes sense.

Good organization includes staying on topic (since this is a short essay), and that implies that there is a thesis that organizes the essay tightly. It is very helpful if the thesis is in the first or second paragraph and that there is a final paragraph summarizing what was just said (this would follow a conclusion paragraph if you have one—conclusions are the final result of your analysis, summary paragraphs are restatements of the essay, including a conclusion, if any). I know it sounds redundant but it is a godsend to tired readers/graders and a great way to check whether you know what you just said.

"Container" style requirements (form)

Standard style requirements that must be part of your essay

General

Style requirements are relevant to ALL components of your submissions. That includes prose comments in footnotes, "How I used this source" sections, etc.

Use MLA style for your essay. (Go to CROSS-COURSE > Key Concepts & Terms "style, documentation (citations) & bibliographies" for links to sites where you can learn MLA style online.)

You will be submitting online and we will be returning your essay with comments on it, in its digital form. We use the comments function of MSWord to write our comments. Therefore, your documents must be MSWord .doc or .docx. Beware of pirate editions of MSWord or MS Open Office. They sometimes create corrupt files.

Spelling, diction, treatment of terms and some other basic formal matters

Font choice. Please use fonts and font sizes that work well on-screen since that is where you essay will be read.

Basic clarity of expression. Please reread and rewrite your paper for clarity. However, it is important that the essay sounds like you. Never have a friend rewrite it for better English or in any other way consult with anyone beyond your research material. This is academic dishonesty under the rules of this assignment since I wish to see your analysis. Contacting others or having them polish the English will result, at minimum, in an "F" for Step 03, no exceptions. I might also convert the Step 02 score to "F" and I might disqualify you from submitting Step 04 and I might give you an "F" in the course and I might report you to the University. If you feel your English will not be well understood by us, you can include a SECOND, edited version. Make sure you do NOT edit the original except by yourself. Keep a separate copy of that work, before you begin to consult someone else. It is unlikely I will have time to contact you about a problem at Step 04. I might be able to contact your at Step 03. However, I reserve the right to make my own conclusions about your work without contacting you, if time is limited.

Academic diction. Your essay language should be semi-formal or formal. You can use "I" but please avoid causal phrasing and never use contractions (write "do not" not "don't"). Stay decent: use "urinate" not "piss" and so on. Sound smart: use "two men in particular advanced the ideas of the shin-kankakuha movement" not "two guys …" Avoid being chatty, clever, etc. Sound balanced and reasonable but not cold and disinterested.

Spelling. Spelling should be nearly perfect through all parts of the essay, including footnotes and all bibliography components. Spelling should be 100% accurate for all important terms, all names, and so forth. This is true, again, for all parts of the essay, including footnotes and the bibliography components.

Just about any system of romanization of Japanese words is OK, but be consistent. Macrons (the long mark over an "o" or "u" usually) are optional. All of these are acceptable romanization solutions: shinjū, shinjû, shinjuu,shinju. There are other systems, too, such as sinju.

You are welcome to use foreign scripts but when you do so, always include a romanized version since some computers might not convert the script properly. Ex. 大阪 [Osaka].

Punctuation. I am not strict about punctuation. If you give it a decent effort you should meet my common sense standards.

Treatment of book and article titles. Please get this right! Academic readers want to know the nature of your source, and this is indicated, in part, by how you style it. Many students read online prose (in blogs, etc) than academic prose. The New York Times, for example, uses quotation marks for books. Please note the distinction between style environments. We are working with academic language that, in theory, will be in print form, not online; it has its own specific conventions.

- Articles, book chapters, short stories, and films use double quotation marks: "A short essay on commas" or "Star Wars".

- Books and web site titles are italicized: The Tale of Genji and Wikipedia.

Treatment of foreign terms. Foreign nouns that are not names of places, people or historical periods and that are not common should be italicized: chashitsu (not part of normal English usage) but sushi (part of normal English), "Emperor Suzaku" not "Emperor Suzaku", "Heisei period" not "Heisei period" and so on.

Use just the last name of a scholar when you explicitly mention him or her in the body of the essay. Do not mention him or her in the body of the essay unless s/he are of particular import. (If they are key to your essay, mentioning them signals the reader that your work has taken special note of that scholars work.) Sometimes it is helpful to say a bit more. If you are writing about Japanese poetry and the scholar is know for Japanese poetry there is no reason to say "the scholar of Japanese Poetry Suzuki" or whatever. However, if Suzuki happens to be considered one of the most famous scholars on the topic it is fine to say something like "the widely respected scholar of early Japanese poetry, Suzuki ..." And, if your topic is sumo there are not a lot of sumo scholar so saying "Takahashi, a scholar of the origins of sumo, say ..." since the reader is probably assuming that sumo is a secondary topic to any scholar. So, it is a judgment call: a) decide how important it is to identify the scholar in the body of the work rather than just in the footnote, b) decide if details about the scholar are needed given your guess regarding the expectations / assumptions of the reader..

Documentation (cites / bibliography)

First, footnotes—NOT in-line parenthetical citations—are required. While in-line citation is now standard, for various reasons I need the details possible in the footnote.

Therefore, you cannot write:

Strunk insists "that every word tell" (Strunk, 62).

You must instead insert a reference number, then a footnote (not endnote—that is elegant for hard copy essays but requires lots of scrolling for reading on-screen).

Footnotes are going out-of-fashion and it is not as easy to find Web-based examples of footnote form. Here is a good Web site that has examples of most types of source material, giving for the first and subsequent citation forms: Footnote/Endnote Citation Form: A Short Guide by Steve Volk. This is based on the Chicago Manual style, not MLA, which has a clean, simple approach. Feel free to use it. ... Here is a link to an old MLA style sheet (—by the way, please do not underline titles; please italicize them. Underlining was the required form before the days of word-processing): MLA Style Sheet for Bibliography and Footnote/Endnote Citations. ... If you want to practice converting raw bibliographic information as you would encounter it online in various locations (Amazon, JSTOR, etc) I have a short exercise: Practice Making Citations.

If your citation is a direct quote, footnote markers come directly after the quote.

If it is not a direct quote, footnote markers usually come at the end of the sentence, but sometimes come at the end of a clause. THE IMPORTANT THING IS THAT A READER CAN EASILY UNDERSTAND THE BOUNDARIES BETWEEN YOUR IDEAS AND THOSE OF THE INIDIVUAL TO WHOM YOU REFER. Locate footnotes accordingly and WRITE IN A WAY THAT HELPS KEEP THE BOUNDARIES CLEAR. For example, add phrases such as "While O'Brien argues, xxxx, in my opinion, yyyy."

Footnote markers occur outside the quotation marks, not inside them except is special circumstances. Also, they come after punctuation, not before it.

One footnote per footnote marker.

Accurate attribution. Please remember, if you are quoting Ralph who is quoting Minnie Mouse as saying that all holidays are depressing, critique Minnie Mouse NOT Ralph! It is her idea. Further, make sure we know this is going on.

Citations point to specific locations in a text. Do not cite "Chapter 1" or the book as a whole or "in the first half of the book". Give an ACCURATE page number.

When to cite

General comment. When you are quoting someone either directly or in paraphrase, cite the source. When you are offering an idea that relied heavily on the idea of another, cite the source. When you think the reader would like to go to the source later on her or his own, cite the source. When in doubt, cite the source.

When to cite—details.

It is a judgment call. Too many footnotes clutter the work, too few degrade the academic quality of the work. Here are common scenarios when I would like to see citation:

The idea (conclusion, analysis, speculation) or information was generated with some effort by the scholar and that scholar deserves credit for it. "Forty percent of individuals who use ivory chopsticks while less than 10 years old develop arthritis earlier than average." That claim would have been the work of someone, obviously not you, and that person needs to get credit for it. Not to do so is a serious error in citation, one that is punishable. It is plagiarism even if you just messed up and forgot to cite it. There is very little room for forgiveness.

The idea (conclusion, analysis, speculation) or information is such that it is likely the reader would like to know more. You point them there. Your citation is serving the function of enhancing scholarship by making resources accessible.

The idea (conclusion, analysis, speculation) or information is counter-intuitive or for whatever other reason is likely to generate doubt in the reader's mind. "There is a much greater quantity of water on the moon that was believed to be true previously." This is a true statement; however, there are probably readers who wouldn't think so. You protect yourself by documenting it. On the other hand, "There is considerable racial diversity among students attending Cal" won't be questioned by your readers. However, if you lived in a country that did not know much of the outside world and didn't have racial diversity, they might not believe you and you would need to cite this. See how it works? There are no definitive rules; there are lots of judgment calls to make.

Direct quotation AND paraphrasing of course absolutely must have documentation. Further, the quote, whether direct or in paraphrasing, must be accurate, not modified to support your argument. Not doing so is also a serious type of plagiarism that can have the most severe of penalties.

Not every sentence needs a cite. Good judgment can be used here. When a scholar is cited and there is other similar information mentioned in something of a prose flow that could link all the comments together, the reader is likely to conclude that the other pieces of data are from the same source. (Ideas are a bit trickier. It is better in the case of including a scholar's ideas — conclusion, analysis or speculation — to cite, to be on the safe side.) However, if more than one scholar is being cited in a back-and-forth manner or, for example, if one scholar is cited at the beginning of a paragraph and a different one at the end and the middle data is not cited, then it is hard for the reader to make a decision on the source. Plagiarism intentional and unintentional very frequently happens when the data is cited but not the analysis, leaving the impression that the facts come from someone else but the conclusion is yours. Be very careful to avoid this type of readerly misunderstanding.

Finally, and this is a very serious problem, plagiarism occurs sometimes when you have forgotten that something wasn't your idea. It slipped into your head while reading, it interested you, time passes, and you begin to think you own the observation or conclusion. Good research reading (not jumping all over the place, such as what happens when reading a number of web pages at a time), good note taking (because if you write it down, even once, it is less likely for you to forget that you learned it from someone else, not from your own brain workings), and writing drafts from notes are ways of reducing the chance of this slippery problem. Remember that you have no defense: if you present an interesting idea as your own and it appears in a work you are likely to have seen (even if you didn't), no one will believe that by coincidence your idea matches what is written. Nearly everyone, including the courts, will conclude that you have forgotten, intentionally or by accident, that you read it somewhere first.

When to quote

Assume that, as graders, we are somewhat impatient with quotes. They simply take up space where you could be offering your ideas. Use quotes only when very useful, never as decoration or to fill space.

Special style requirements that must be part of your essay

Your title is graded. Your title must be an "informative title".

Please write an informative title, not a general one. The title is the first thing any prospective reader will check and if it is not specific, you will be ignored. Please also avoid clever titles unless it is both clever and informative. Here are some examples from previous semesters, with my candid reactions. Please remember that they had an entirely different assignment, so your titles won't look much like these:

Construction of the Feminine Ideal in Edo Japan

This is rather nice (but would be better as a 40-page paper).

Okashi's Influence on Heian Serving Ladies in Sei Shonagon's The Pillow Book

This is troubling since okashi is a literary term and doesn't really influence real people ... or does it? I couldn't tell if the student was about to write something really interesting or was being a bit sloppy in language use.

The Meaning of Japanese Sword

WAY too general!

Marriage and Politics of the Heian Society

Not bad. Almost too general. Hopefully this is about the relationship of marriage and politics not just a list of "about marriage, about politics ....".

How the Hiragana Derived from Chinese Characters

Clear, but the project lacks ambition.

Warriors of Heike: For whom do they bleed?

Too clever to tell me much. Fun, however.

The Oni Within

Huh? Need more!

The women—for the Heian period of Japan

WAY too general.

Honor as Performance in The Tale of Heike

Almost good. It is a bit puzzling as a title, but intriguing.

Origin of the ninja popular culture

"Origin of ..." usually makes me nervous. It is not so easy to pull off such a topic in a few pages. Most "origins" are pretty complicated. And, what, exactly is "Ninja popular culture"? Something like "Possible origins of ninja as portrayed in the video game xxxx" would be more satisfying and believable as a title.

How Women Rule in Tale of Genji

Sounds a bit too pre-decided as an essay but has a certain appeal. Not bad.

Additional, special components for the footnote

*This is required ONLY of the second essay.

We check how you have drawn on your sources in specific places in your essay. In order to do this, we need to be able to go easily to the exact location that you refer to in your footnote. Therefore, although this is NOT part of proper essay form and should NOT be used in any other class, I require that each footnote have, below the regular citation, exact location information.

"Exact location information" means we don't have to read several pages or even a page to find your location. You point us to the correct paragraph or whatever is necessary so that we can very quickly locate your location.

- If it is a search-able, electronic source, you might be able to say "search 'it is believed he finished the work in 1694'" or such if there are no page numbers, but avoid generic phrases such as "he finished the work". Test your search string, carefully.

- If it is a hard copy you must provide the scan. Title it like this author - short title - page, so, for example, Ueda - Interpreters - 22-25. Then, as location, used that file title. For example, "Location: 2nd paragraph on page 23, in the scan Ueda - Interpreters - 22-25."

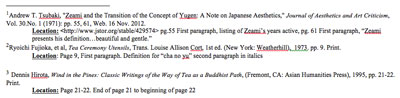

Example. You can deviate from this. The basic principles are four: 1) easy to read, 2) separate from the regular footnote, 3) accurate, 4) we can quickly find the exact location.

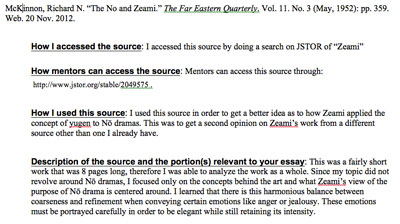

Additional, special components for the standard bibliography

*This is required ONLY of the second essay.

We check how you have found and used your resources. I therefore require that you tell us how you found your resource (be specific, don't just say "Web" or "Went to the library", instead say "JSTOR search" or "Found the call number through Oskicat then went to Doe"), how we can check your resource (its URL or if you have included scans, the title of the file or files), how you used the resource and a general description of the resource. Follow the format as in the example below.