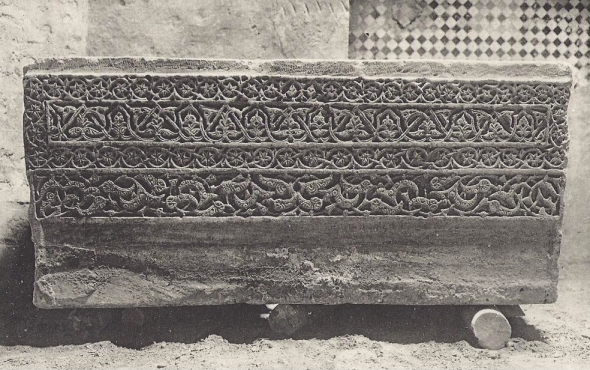

Figure 37. Carved stone fragment from Madīnah al-Zahrā', unlocalized; Velázquez Bosco, Medina Azzahra, pl. 31, top left.

Table of Contents

The main entrance frieze, the palmette frieze of the sixth register of the cylindrical section of the northern minaret, and the window frames of the seventh register of that minaret are characterized by what I call “direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament”. In the main entrance frieze a geometric design formed by a flat band is integrated directly with foliate elements. The flat band both grows from palmettes and sprouts their grooved stems. In the window frames the geometric and geometrized shapes are formed by stems that also bear foliate elements or grow from them. Samuel Flury seems to have noted the same characteristic in the palmette frieze of the sixth register, as he remarked on its “organic combination of foliate and geometric motifs” (organische Verbindung der vegetabilischen und geometrischen Motive).63 This integration is both thoroughgoing and consistent.64

This integration is unusual in Islamic art and almost unknown in Antique and Late Antique art. The arabesque, as I see it, is essentially the shaping of foliage and other decorative forms into geometrically determined curves and cusps. But foliate arabesques generally do not include angular geometric forms such as five-pointed stars, and in Islamic art angular geometric frameworks do not generally grow leaves. I have found significant parallels for this direct integration only in Umayyad Spain.65

Figure 37. Carved stone fragment from Madīnah al-Zahrā', unlocalized; Velázquez Bosco, Medina Azzahra, pl. 31, top left. |

Direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament occurs generations before the Mosque of al-Ḥākim in Umayyad Spain, in the mid-tenth century at Madīnah al-Zahrā', which has been heavily reconstructed. Published material includes photographs of the fragments in which the carved stone was found, the reconstructions into which the fragments have been assembled, and analyses of what portions of those reconstructions are original. The photographs of fragments are important in showing that the characteristics of the designs I discuss here are not figments of reconstruction, whether or not the reconstructions are entirely correct.

There is some quite complex and inventive stone decoration at Madīnah al-Zahrā', but in the rest, despite some variation in quality and some increase in complexity over time, the same forms occur from beginning (the mosque) to the end (the Salon Rico), nearly all executed in the same technique: shallow relief in which the forms are sharply grooved. I conclude that the bulk of the stonework at Madīnah al-Zahrā' was the output of a single workshop. Throughout, the foliage grows from grooved bands that form geometric or clearly nonfoliate patterns. The designs used varied according to the elements of decoration: a pilaster base, fields, borders, and pseudovoussoirs.

Below I list substantially all the published fragments from Madīnah al-Zahrā' I have found that include direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament, and in which the geometric design is angular rather than geometrically curvilinear—though there is a good deal of that too. In these fragments grooved bands form continuous geometric designs that also sprout stems and leaves directly (the foliage is not simply juxtaposed to the geometric design, and there is no dividing line between a geometric form and a foliate form connected to it). The geometric designs can be seen as geometrized stems or as angular frameworks; clearly foliate stems are generally the same width as the geometric bands and grooved the same way.

The unlocalized carved stone fragment published by Ricardo Velázquez Bosco and illustrated above, probably came from the Dār al-Mulk, for which see below.66

Two unlocalized carved stone fragments published by Henri Terrasse.67 As they were published in 1932, before the excavation of the Salon Rico in 1944, they too probably came from Velázquez Bosco's excavations in the Dār al-Mulk. Other fragments with geometrized stems are visible in the same photograph, laid out on the ground.

A carved stone pilaster base from a door in the east wall of the Salon Rico illustrated by Henri Stern.68

Salon Rico, carved stone ornament published by Natascha Kubisch.69

Salon Rico, carved stone ornament published by Christian Ewert, in various states of restoration.70

Carved stone fragments from the mosque, the Salon Rico and adjacent areas, the “Palacio de Don Ricardo” (which I believe is the area marked “A” on Velázquez Bosco's map, thus the Dār al-Mulk)71 and unspecified locations, published by Pavón Maldonado, some more than once, in El Arte hispanomusulmán en su decoratión geometrica and El Arte hispanomusulmán en su decoratión floral.72 I do not accept all of Pavón Maldonado's localizations without reservation, and even if they are correct findspots, the site was disturbed by looters from the eleventh century onward, so the findspots of some fragments may not correspond to their origin. Some of the decoration published by Pavón Maldonado was subsequently republished by Kubisch and Ewert.

D.F. Ruggles and Natascha Kubisch have separately summarized the chronology of Madīnah al-Zahrā' and the distribution of the excavated remains.73 The complex was begun in 325/936 and work continued for forty years. The mosque was built in 329/941 (although not necessarily completely decorated then). Three capitals excavated in the Salon Rico are dated in the years 342–45/953–57, during the reign of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III (300–350/912–961). Two capitals with the name of al-Ḥakam II were found in the ruins of the Dār al-Mulk, which should date at least part of its decoration to his reign, 350–66/961–76. Madīnah al-Zahrā' was sacked in 401/1010.74 Kubisch believes that palace building at Madīnah al-Zahrā' ended in 366/976 with the accession to the caliphate of al-Hishām II, as al-Manṣūr, his hājib, built Madīnat al-Zāhirah as a competing princely development in 368–70/978–81.

Other, less angular examples of direct integration are fairly common in Umayyad Spain; they generally involve segments of circles.75 Below I consider the more outstanding comparative material involving angular forms.

Direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament involving simple frameworks occurs in the mosaic intrados of four of the eight interlaced arches of the antemihrab dome of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, 354/965.76 Here a series of squares is set diagonally, corner to corner, joined by small circles; the squares sprout internal foliage and the remaining triangular spaces contain foliate fillers not connected to the squares. Contrast the other four arches,77 which are simply interlacing foliate scrolls with fillers.

A single casket from among the group of Spanish Umayyad ivories has a design in which an angular geometric framework is directly integrated with foliage. It is in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris (no. 4417), and is dated 355/966.78

Figure 38. Marble water trough, Gallotti, pl. 1 and 2. |

A Spanish Umayyad marble water trough also has a zigzagging angular geomtric framework that sprouts foliage, like the ivory casket and the Madīnah al-Zahrā' column base already mentioned. It was found in the Madrasah Bin Yūsuf in Marrakesh, and is now in the Matḥaf Dār Sī Saʿīd in Marrakesh.79 It dateable to the years 392–98/1002–07 from the inscription in the name of ʿAbd al-Malik, son of al-Manṣūr, who were both in succession the hājib of al-Hishām II.80 The original publication of this object was by Jean Gallotti, “Sur une cuve de marbre datant du khalifat de Cordoue (991–1008 J.-C.)”.81 Gallotti disengaged the item from the location where it had been immured and noted the phenomenon of a central origin of ornament in the framing band's intertwining foliage, which then runs to either side with symmetry of reflection.82

The carved stonework of Madīnah al-Zahrā', some other Spanish Umayyad art, and the carved stone ornament of the Mosque of al-Ḥākim share the unusual feature of direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament. This apparent connection could have come about from derivation from a common source if direct integration had been a Late Antique design characteristic or an early pan-Islamic one. In this section I survey what little evidence there is for this possibility.

In some capitals in Hagia Sophia foliage may be seen as growing in some places from geometric frameworks, but this effect occurs rarely and inconsistently; most often these might be called “attached filler elements”; that is, I believe these foliate elements were intended to be “fillers” (more respectfully, interstitial components of design) and that the apparent connections with geometric frameworks are accidental. The same is true of contemporary capitals and window grilles from Ravenna in the same style and, I believe, the same material. There are, however, some cases in Hagia Sophia in which the effect is clearly deliberate.83

In the plates of Ernst Herzfeld's Der Wandschmuck der Bauten von Samarra und seine Ornamentik one can find stems of foliate ornament that appear to grow from the framing bands. An example from the Third Style is pl. 92, top, orn. 274, in the lower register (cf. pl. 94, orn. 274). While this could have been deliberate, it could also have been sloppy execution or an error by the carver in interpreting the design as it had been scratched out for him.84 In addition, these stems are not the width of the full border band but only of one edge, and they grow from the edge of the border band only occasionally. In the case of the First Style (the Bevelled Style), there can be deliberate ambiguity between border and field, as in pl. 33 and 34, orn. 94, and p. 53, orn. 144, where the border band, not obviously foliate, extends into the field between forms that in other cases abut each other directly (cf. pl 34, orn. 95). Neither case seems to be related to the direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament of Madīnah al-Zahrā'.

Figure 39. Balkh, Mosque of Ḥajī Piyādah. |

Samarra-style stucco in the Mosque of Ibn Ṭūlūn in Cairo85 and the late ninth-century Mosque of Ḥajī Piyādah outside Balkh86 offer other examples of foliage growing from one edge of a border band.

This meager group includes all the examples I have found of direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament before Madīnah al-Zahrā' and none of them is thoroughgoing and consistent in the way the direct integration there is. I conclude that there was probably no early Islamic source for direct integration;87 there could have been a source in Byzantine stonework, but if so all intermediaries are lost. So almost certainly there was some direct connection between Madīnah al-Zahrā' and Cairo.

Aside from a single comparison of palmette forms by Creswell, which he did not follow up, I have not found a connection between Cordoba and the Mosque of al-Ḥākim suggested in the literature. Marianne Barrucand, writing on the topic, ironically, in Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā', considered only Byzantine, Aghlabid, and Fāṭimid sources.88

Certainly if building activity declined in Cordoba when Madīnat al-Zāhirah was completed in 370/980–81 or there was a period at the beginning of al-Hishām II's reign (before al-Manṣūr took power) when building ceased, or work was scarce in the latter years of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān's reign following the completion of his expansion of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, Cordoban stonecutters might have looked elsewhere for work. And it is an interesting coincidence that this is just the time when the caliphal palace in Cairo was being built—of stone, if Nāṣir-i Khusrau can be believed.89 As I remarked at the outset, the Fāṭimids had no previous record of fine stonework before the foundation of Cairo, and Islamic Egypt had no fine stonework either. The Fatimids must have obtained workmen from somewhere by the time the Mosque of al-Ḥākim was built. They could have come from Syria or Jerusalem, but at least some of them might also have come from Spain.90

It is worth considering how workmen from Cordoba would have gone about finding work in Cairo. Had they simply shown up there without introduction they would have faced the problems of determining whom to approach, how to demonstrate their competence, and possibly the professional jealously of their peers. As political relations between the Spanish Umayyads and the Fāṭimids were hostile, it is unlikely, though not impossible, that they were referred from one court to another by some important figure.

Two principal possibilities occur to me. It is possible that Spanish masons were established in Egypt even before the Fāṭimids conquered it; a continuous series of transfers of workmen from Cordoba to Egypt (rather than one mass transfer) would have given the newcomers intermediaries to rely on. However, there is no evidence of the work of Spanish masons in Egypt or the Fāṭimid lands before the Mosque of al-Ḥākim, with two exceptions: the marble panels lining the niche of the mihrab of the Great Mosque of Qayrawān and similar panels in the Great Mosque of Tunis.

[Link: Great Mosque of Qayrawān, mihrab (an image on the site of the Museum With No Frontiers, Brussels).]

The marble panels of the Qayrawān mihrab, some of which are partly openwork, are well known if not well studied.91 There is some controversy over which phase or phases of the mosque the mihrab belongs to, and hence its date, as well as the intent behind the openwork, but these disputes are not relevant here. According to any dating the marble panels belong to the second half of the ninth century.

Creswell thought the best source for dating the mihrab was the Maʿālim al-īmān of Qāsim b. ʿĪsā b NāJī (d. 837/1433–34), who cited Abū Bakr al-Tujībī, d. 422/1031. This text, with translation, was first published by Georges Marçais.92 In Creswell's transation, Ibn NāJī reports “and he [the amir Abū Ibrāhīm Aḥmad] had the mihrab brought from Iraq in the form of panels of marble”, which is also where the wood for the minbar (or the already fabricated panels of the minbar) are supposed to have come from. The text clearly says the marble panels came from Iraq, although possibly it is corrupt in some way. However, the panels can hardly have come from Iraq.

The central column of panels, and some others, are carved in the form of horseshoe arches on columns in rectangular frames, with rosettes between the columns. A very similar panel from the Great Mosque of Tunis was published by Slimane-Mostafa Zbiss.93 It differs in having a broad decorated frame and a tier of crenellations above the arch (so it is not somehow from the same batch as the Qayrawān panels). Zbiss wrote that this and other plaques are in the arcades below the ceiling, mostly in the center aisle. He was not able to distinguish the designs of most of them.

I conclude that there was a workshop making these panels, perhaps most commonly in mihrab form. The openwork at Qayrawān suggests that the workshop may have been composed of artisans who made normally made window grilles. This could well have been an export industry operating in Cordoba. If so, then in the nineth-century Maghrib Cordoba had a reputation as a source of fine stonework. The Fāṭimids may have known this and may even have recruited masons from Cordoba.

63. Flury, op. cit., p. 46 and pl. 20, reproduced in Creswell, op. cit., pl. 25 b.

64. It was anticipated in a minor way in the Mosque of al-Azhar, 359–61/970–72. On the northeast wall of the original prayer hall the upper part is covered with carved stucco, which is probably original; it was discussed by Creswell, Muslim Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, pp. 57–58, with reference to a small variation in dating by Samuel Flury, “Le décor épigraphique des monuments fatimides du Caire”, Syria, v. 17, 1936, pp. 365–76. The relevant plates in Creswell are 9, a, and 11, a, where the frieze above the lower inscription band appears original; Creswell's figures 18 and 19 reproduce drawings from Flury's article. At the bottom of the frieze above the lower inscription band segments of a straight thin band or stem run immediately above a similar band that is the lower border; on every other axis of the design they rise around a foliate element and curl around to turn into two half-palmettes that grow together with each other.

65. In the following discussion I shall not try to coördinate terminology with my 1988 description of the arabesque and its development (Terry Allen, Five Essays on Islamic Art, 1988, pp. 5ff.), but rather describe things as I see them today. I emphasize angular geometric forms here, as opposed to curvilinear forms such as guilloches, to make my point clearer.

66. Medina Azzahra y Alamiriya, pl. 31, upper left.

67. Op. cit., pl. 10 (see footnote above).

68. Les Mosaiques de la Grande Mosquée du Cordoue (Madrider Forschungen, v. 11, Berlin, 1976), pl. 50, b. A fragment of this base was published in an oblique view by Pavón Maldonado, Decoratión floral, pl. 5-15, 115.

69. “Der geometrische Dekor des Reichen Saales von Madīnat az-Zahrā'”, frieze below the ceiling, pl. 55 a; and framing band of arcade, pl. 56 and 57.

70. Ewert, Dekorelemente.

71. The Dār al-Mulk is labelled on a plan at the web site of the Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra, which in September 2010 was at http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/cultura/media/fotos/CAMA_recorrido_popup2_2.jpg.

72. A cautious selection includes: El Arte hispanomusulmán en su decoratión geometrica, 2nd ed., Madrid, 1989, pl. 31 (two fragments), 32 (upper right), and 40 (lower left); idem, El Arte hispanomusulmán en su decoratión floral, (photographic plates, using the full weird plate numbering) pl. 1-2, 5, 13; 1-3, 20 (left fragment); 1-5, 47, 49; 3-10, 84; 8-9-18, 142-2 (five fragments); 8-9-19, 144, 145, 148; 8-9-20, 154, 155; 22-74, 461; 22-75, 467, 468; and 8-9-128, 658 (left).

73. Ruggles, Gardens, Landscape, and Vision in the Palaces of Islamic Spain, Univ. Park, Penna., 2000, pp. 56–85; Kubisch, “Geometrische Dekor”, pp. 303–05.

74. Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., s.v. “Madīnat al-Zahrā'”.

75. A short list: Cordoba, Great Mosque, jamb of mihrab doorway; Madīnah al-Zahrā', Salon Rico, fields 29, 51, and 57, Ewert, “Dekorelemente”, pl. 58, 111, and 114; ivory pyxis, New York Hispanic Society, Ernst Kühnel, Die Islamischen Elfenbeinskulpturen VIII–XIII. Jahrhundert, Berlin, 1971, pl. 14, no. 28 e; ivory pyxis, Madrid, Museo Arqueológico Nacional, from the Cathedral of Zamora; op. cit., pl. 12, no. 22 b, c.

76. Henri Stern, op. cit., pl. 20, b, and 21, a, each shows the lower sections of two different arches. Stern's pl. 62 and Barrucand, op. cit., p. 78, shows the arches from below.

77. Stern's pl. 20, a and 21, b.

78. Kühnel, Elfenbeinskulpturen, no. 25, pp. 55–56, pl. 15.

79. The secondary literature I know of is: Terrasse, op. cit., p. 167, pl. 37; a remarkably negligent entry by Juan Zozaya, in the exhibition catalogue Al-Andalus, the Art of Islamic Spain, ed. Jerrilynn D. Dodds, N.Y., 1992, p. 255 (photograph mirror-reversed; the text, never proofread and missing most of the literature on the object, incorrectly states that the inscription is unpublished, and that the basin “has not been moved in centuries”); Natascha Kubisch, “Ein Marmorbecken aus Madīnat al-Zahīra im Archäologischen Nationalmuseum in Madrid”, Madrider Mitteilungen, v. 35, 1994, pp. 398–417, p. 409 (with full bibliography), pl. 53.

80. E Lévi-Provençal, Inscriptions arabes d'Espagne, Leiden, 1931, pp. 194–95.

81. Hespéris, 1923, pp. 363–391 (pl. 1 reproduced by Kubisch, pl. 53 a).

82. Pp. 366–67.

83. For attached filler elements see Rowland Mainstone, Hagia Sophia, Architecture, Structure and Liturgy of Justinian's Great Church, N.Y., 1988, fig. 74, and Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann, Ravenna, multiple volumes, Wiesbaden, 1969–89, several reprints, v. 1, fig. 66, 77–83; v. 2, fig. 37–56, including some comparative material. For a clearly deliberate example see Christine Strube, Baudekoration im Nordsyrischen Kalksteinmassiv, 2 v. (Damaszener Forschungen, v. 5 and 11, 1993–2002), v. 2, pl. 9, d. The geometric framework of interlaced zigzags that appear to form parallelograms occurs at Khirbat al-Mafjar in the right side of the dīwān apse, Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture, 2nd ed., v. 1, pt. 2, pl. 109, c.

Attached filler elements also occur in floor mosaics in Anatolia; see Sheila Campbell, The Mosaics of Aphrodisias in Caria, Toronto, 1991, pl. 115 and 116, the House by the City Wall.

84. Herzfeld, Wandschmuck, pl. 30, orn. 156, shows such a scratched design.

85. Stern, op. cit., pl. 53.

86. Lisa Golombek, “ʿAbbāsid Mosque at Balkh”, Oriental Art, v. 15, 1969, pp. 173–89. Barbara Finster, Frühe Iranische Moscheen (Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, Ergänzungsband 19), Berlin, 1994, pp. 175–81; pl. 9–13 are good views of the ornament on the intrados of the arches.

It is interesting that the Antique geometric frameworks seen in the soffits of the arches in the Mosque of Ibn Ṭūlūn are absent at Samarra.

87. Also interesting is that there seems to be no bevelled style ornament in any medium in Islamic Spain.

88. Creswell, Muslim Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, p. 70; Barrucand, “Le premier décor de architectural fatimide en Egypte”, Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā', v. 5, 2004, pp. 405–62.

89. Creswell, op. cit., v. 1, p. 33. Some of what Nāṣir-i Khusrau wrote about Cairo is entirely incredible, however. I assume that the palace was not completed or at least not completely decorated at the time it was first occupied in 362/973.

90. Bloom, “Mosque of al-Ḥākim”, p. 26, wrote without support that the motifs of the carved stone decoration of the main entrance are “undoubtedly the products of a local main d'oeuvre”.

91. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture, 2nd ed., v. 2, pp. 308, 314. The latest academic publication regarding the mihrab that I am aware of is Christain Ewert, “Die Dekorelemenete der Lüsterfliesen am Miḥrāb der Hauptmoschee von Qairawā (Tunesien)”, Madrider Mitteilungen, v. 42, 2001, pp. 243–431, who cited no literature regarding the marble panels. Ewert and Jens-Peter Wisshak, Forschungen zur almohadischen Moschee, v. 1 (Madrider Beiträge, v. 9), pp. 15–20, discussed the plan of the mosque and n. 98, pp. 15–18, reviewed the literature. Directly on the topic is Lucien Golvin, “Le miḥrāb de Kairouan”, Kunst des Orients, v. 5, fasc. 2, 1968, pp. 1–38, but Golvin did not deal with the provenance of the marble panels.

92. Les Faïences a reflets métalliques de la Grand Mosquée de Kairouan, Paris, 1928, p. 10.

93. Corpus des inscriptions arabes de Tunisie, pt. 1 (Direction des Antiquites et Arts, Tunis, Notes et Documents, v. 13, fasc. 1), Tunis, 1955 (no more published), p. 30 and pl. 3, no. 4.