Table of Contents

There are uses of symmetry in art and architecture that are not captured by the mathematical study of the symmetry of figures in a plane.

Some sets of designs exhibit identical combinations of symmetries. I call these combinations “constructs of symmetry”.

Constructs of symmetry are common in the art of all cultures; Islamic art is particularly rich in them, and consequently they deserve special attention, the more so as historians of Islamic art have not generally made a point of specifying either their component symmetries or their overall organization.

Figure 1. A modern Bukhara carpet, detail.

The modern Bukhara carpet of which I illustrate a detail is representative of a set of carpets that share the same combinations of symmetries. As an exercise, and to illustrate the concept of a construct of symmetry, I shall give a brief outline of them. The main body of the carpet is composed of a central field and a main border with “guards” on the inside and outside of the main border. The symmetries of these components are these (omitting consideration of them as two-color patterns):

The main field is composed of “guls” that have one symmetry of rotation but none of reflection and interstitial elements that have fourfold symmetries of reflection and rotation. The main field as a whole has only the symmetry of rotation of the “guls” and (if one considers it extended indefinitely) symmetry of translation along the long and short axes of the carpet and any diagonal that passes through the center of any two “guls”.

The pattern of the main border is similarly composed of two elements (distinguished by their color combinations) that have fourfold symmetries of reflection and rotation. Each of the four sides of the main border has symmetry of translation along its long axis. Note that the short sides are butted against the long sides rather than neatly turning the corner; as the elements of the main border are wider than they are high there is a difference between the long and short sides of the border. However, conceptually (and in other carpets, actually) the alternation of the two elements continues after a 90° reorientation. I have found no mathematical description of this particular kind of change, but there should be one; if the elements themselves are as wide as they are tall and have symmetry of reflection, turning the corner creates (ideally) a symmetry of reflection along the diagonal through the corner element.1

The guards are composed of a central strip that has symmetry of translation only (because of the distribution of colors in its elements) and turns the corner in the same manner as the main border. The central strip is flanked by identical strips of tuning-fork-like elements (choosing one view among several possible) of alternating color; they have symmetry of reflection and translation; the two strips considered together have symmetry of glide translation (because of the offset arrangement of the two colors of their elements). They too turn the corner in the same manner as the main border. The three strips of the guards are separated from one another, the main field, and the main border by very narrow strips of tiny alternating white and black rectangles, which have symmetry of translation and reflection; I believe that within each pair of these narrow strips there is no color offset (so they have symmetry of reflection with respect to each other and symmetries of translation along diagonals similar to that of the main field); however, pairs of these narrow strips may be offset from other pairs. Finally, the two guards have symmetry of reflection with respect to each other.

The point of listing these symmetries and their arrangement in the overall design is to show that it can be done and that multiple symmetries are combined within the same design. Investigation of a larger number of carpets of this type would determine what symmetries and arrangements in the list above are characteristic of the type rather than incidental in this example. As the group of symmetries of carpets of this type is likely to differ from those of other types of carpets, the construct of symmetry characteristic of this type probably can be used to classify it and differentiate it from other groups of carpets.

Of course buildings and art objects often have significant symmetries that disappear when one examines them rigorously. That is, at a certain level of detail there may be differences, either of execution or of design, which one may want to overlook in order to discern the symmetries (or possible alternate symmetries) intended by the designer.

In this article I am particularly interested in designs in which the symmetries involve sets of similar elements, rather than the dissimilar main field and borders of a carpet design. I am not concerned with the symmetries of individual elements, and I confine myself to architecture.

Returning to the Alhambra, and to the point of origin of this study, I want to examine a construct of symmetry peculiar to western Islamic architecture: the use of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms, in this case the bays of an arcade. I am interested only in cases in which the subsidiary axes of symmetry are distinguished by some change in the design of the elements.

Georges Marçais thought that the bays of the arcades of the Court of the Lions in the Alhambra of Granada (attributed to the Naṣrid sultan Muḥammad V, on the basis of inscriptions, 763–93/1362–91) have multiple overlapping systems of symmetry (of reflection), created by variations in arch profile and the choice of single or double columns as supports.2 A bay that participates in more than one system of symmetry he considered as a organe de liaison. In this context it is the bays that are the elements that are arranged symmetrically.

I prefer to illustrate the construct of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms with a simpler example from the Alhambra: the courtyard side of the arcade on the north side of the Court of the Myrtles, in front of the Sala de la Barca and the Hall of the Ambassadors (datable by inscriptions in the entry behind it to after 770/1369).3 While restored, it retains the decorative patterns it bore in the mid-nineteenth century.4 I shall consider only a few of its many decorative details.

Figure 2. Alhambra, Court of the Myrtles, north arcade, general view and detail of two stucco patterns.

Figure 3. Alhambra, Court of the Myrtles, north arcade, detail of west side and capitals of west side.

Figure 4. Alhambra, Court of the Myrtles, north arcade, muqarnas and foliate capitals.

The arcade has seven bays. The central bay is larger than the rest and rises to the top of a framework of rectangular strips. This framework divides the area above the tops of the lower side arches into fields corresponding to the bays. Each of these fields is filled with relief decoration in stucco, as are the spandrels of the central arch. These spandrels share one pattern and the side fields are filled with one of two other patterns, in the following order:

B C B A B C B

Here there are three axes of symmetry of reflection: one in the center, relating to the entire arcade, and one in the center of each of the two wings, relating only to the individual wings and not involving the central bay. This arcade is an example of a construct of symmetry because there are three instances of symmetry of reflection. In order to consider only coördinate forms—bays of the same size—one must either disregard the larger size of the center bay or omit it from the set of coördinate forms considered (the symmetries are the same whether it is included or not). As all three symmetries involve a set of similar elements (“coördinate forms”), this is an example of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms.

The arcade also illustrates another kind of arrangement that I want to investigate.

The eight capitals of the columns supporting the arcade, two of which are engaged, are of four types. The centermost two are muqarnas, and the others are variations of a foliate capital type common in the west. To mention only a minimum of distinguishing differences (there are many others), the capitals of the columns next to those supporting the central arch have shields centered in each side; the next pair out have pointed ovals in the same place; and the outermost, engaged, pair have shells there instead. Combined with the patterns of stucco decoration in the fields above, these two design choices yield the following arrangement:

B C B A B C B U T S R R S T U

The symmetry of the arrangement of the capitals consists only of symmetry of reflection, but the decoration of each half of the set of capitals is an example of a design principle I call “variation in coördinate detail”. This principle is that, given a set of like elements, one should make each of them different from the rest by varying the details of their decoration while maintaining the same overall texture of that decoration—including such characteristics as scale, degree of linearity, and degree of detail—across the set. This design principle is not a construct of symmetry (it might be called a “design principle employing symmetry”), and it is not necessarily at work in sets of elements that bear some iconographic significance, as variation in such sets may be dictated by their iconography.

The combination of variation in coördinate detail with symmetry of reflection constitutes what I call “variation in coördinate detail with reflection”, which is not a construct of symmetry either, as only one symmetry occurs. This design principle is common in western Islamic architecture, as will be seen.5

The variation in coördinate detail with reflection seen in the capitals coincides with one of the symmetries of the stucco fields in the central axis of the facade, but the arrangement of the capitals does not conform to the triple axis of the stucco fields. That is an aesthetically interesting complication of the overall design of the arcade, but I shall ignore it here. Instead I shall considering separately the construct of symmetry I call subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms and the design principle I call variation in coördinate detail with reflection.

As it happens, at least before 1400 A.D., the arrangement of the decoration of the bays of an arcade so as to produce subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection does not occur in Islamic architecture in the central Islamic lands or in the eastern Islamic world, and I believe that with rare exceptions the more general construct of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms does not appear either.6

The only antecedants I have found for the use of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms in the Court of the Myrtles are three mosques built for the Almohad caliph ʿAbd al-Muʿmin several centuries earlier. The most elegant of these is the mosque at Tinmal, Morocco.

The Almohad mosque at Tinmal, in the mountains south of Marrakesh, was dated to 548/1153–54 through historical sources by Henri Basset and Henri Terrasse.7 The mosque was thoroughly documented and analyzed by Christian Ewert and Jens-Peter Wisshak, whose work this article intersects.8

The Tinmal mosque exhibits subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms in the arcade immediately in front of the qiblah wall. The arcade has nine bays where the nine aisles of the mosque, running perpendicular to the qiblah wall, intersect the aisle parallel to and immediately in front of the qiblah wall. The center and two outermost aisles of the nine are wider than the others, the center aisle being slightly wider than the outermost ones. In the qiblah aisle the outermost and center bays are domed. The remaining six aisles are the same width, with some minor but unsystematic variation.

Figure 5. Tinmal, mosque, arcade parallel to qiblah wall, outermost two bays on east, and west wing.

The center arch of the arcade immediately in front of the qiblah wall is a lambrequin. The outer two arches (assuming the were the same; only the one on the east survives) are similar but slightly different lambrequins. On each side the three remaining arches are of two profiles: in sequence, simply lobed, complexly lobed, and simply lobed. The arrangement may be diagrammed as follows:

B C D C A C D C B

Ignoring the outermost bays, the B's, this arrangement may be considered to have three axes of symmetry, like the arcade of the Court of the Myrtles.

Basset and Terrasse considered the arches of the bays on either end of the qiblah wall (my B's) to have the same profile as the center bay.9 The difference is clearly shown in Ewert's loose plate 10, but it is not unreasonable to imagine that the architect considered them to be the same design or expected them to be seen so, varied only to suit the different width of the relevant bays, in which case the arrangement should be diagrammed

A C D C A C D C A

Seen this way, the two sets of bays governed by the subsidiary axes of symmetry overlap at the center bay. As this analysis produces a tidier result, it may reflect the architect's conception of the mosque—or at least of this aspect of it—better than the one shown first above.

However the end bays are considered, this pattern of symmetry is not carried farther into the prayer hall, nor does it appear on the facade of the prayer hall on the courtyard, where the two outermost aisles on each side continue as riwāqs. There are other aspects of decoration that emphasize the three domed bays and especially, of course, the center bay.

Terrasse connected the multiple arch forms of the Tinmal mosque with the second Kutubīyah mosque in Marrakesh (for which see below), and thought that they were disposed in an “expressive hierarchy” according to the functional arrangment of the mosque's plan.10

Christian Ewert considered the first Kutubīyah mosque in Marrakesh (believed to have been begun in or soon after 541/1147 on historical grounds, also by the Almohad caliph ʿAbd al-Muʿmin) to be the immediate source of the Tinmal mosque in connection with its hierarchical articulation (hierarchische Gliederung), a concept that encompasses my construct of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms but does not entail it.11

Figure 6. Marrakesh, First Kutubīyah Mosque, qiblah wall, general view.

Figure 7. Marrakesh, First Kutubīyah Mosque, qiblah wall, central portion.

Figure 8. Marrakesh, First Kutubīyah Mosque, qiblah wall, east end.

The elevation of the qiblah wall is partially preserved in the north exterior wall of the second Kutubīyah mosque, which was built adjoining the first. This wall had been reworked considerably at unknown dates before the age of photography but has not been altered much since.12 My illustrations are from my visit in 1985. The remains of the qiblah wall show a center mihrab bay, wider than all the others, flanked on each side by three bays with applied horseshoe pointed arches, a bay with no applied arch, and two bays with applied horseshoe arches. Beyond these pairs of bays are two bays without applied arches. The bays without applied arches that are closer to the center show stubs that are apparently the springing of arches perpendicular to the qiblah wall; on the west, the outermost bay exhibits the same feature.13

Jacques Meunié and Henri Terrasse, reporting on excavations on the site of the first Kutubīyah mosque, interpreted the arch stubs in the remains of the qiblah wall as indicating that the bays bracketed by them were vaulted somehow, although they were unable to say just how. They noted that the two bays on the extreme end were narrower than the others.14 They also assumed that the outermost sets of bays with applied arches, which have been heavily reworked, were three bays wide,15 producing an arrangement like this:

C D D D B D D D A D D D B D D D C

where A is the center bay and B and C mark vaulted bays of different widths; if one ignores this variation in width the layout is:

B D D D B D D D A D D D B D D D B

Here again there are three axes of symmetry of reflection: one at A and the other two at the B's in the center of each wing; the outermost bays must be disregarded in either of these two analyses. As at Tinmal, if one generalizes slightly and assimilates all the individually vaulted bays to the center bay the arrangement is:

A D D D A D D D A D D D A D D D A

and like the arrangement at Tinmal, the two sets of bays governed by the subsidiary axes of symmetry overlap at the center bay.

In the second Kutubīyah mosque, which was also built by ʿAbd al-Muʿmin according to a historical source, in 553/1158,16 five bays along the qiblah wall are individually vaulted as in the first Kutubīyah, although the disposition of the various pier shapes does not precisely mirror the disposition of the vaulting.17

If I understand the situation correctly, in each of these bays the three freestanding arches share the same profile, which is the same lambrequin in all the bays except for the center bay, where a similar lambrequin, doubled, sandwiches narrow muqarnas vaults. In the arcade in front of the qiblah wall the arch profiles run as follows (where x is apparently a plain arch, evidently showing a reconstruction of the west side of the prayer hall):

B C C C B C C C A C C x x x x x x

The center bay is the one marked A. Again, the arch profile of the other vaulted bays next to the qiblah wall may be assimilated to that of the center bay, producing this arrangement:

A C C C A C C C A C C x x x x x x

or, restoring the rebuilt section:

A C C C A C C C A C C C A C C C A

This is the same arrangement as in the first Kutubīyah mosque.

There is additional evidence in the second Kutubīyah mosque that the architect considered the vaulted bays as being in some way of the same design: the arcade that includes the prayer hall facade and extends to either side through the four aisles to the east and west of the courtyard. In the nine bays fronting the courtyard this arcade presents different arch profiles on its prayer hall side and courtyard side, those on the courtyard side being simpler. The arch profiles on the prayer hall side are the same as those of the bays along the qiblah wall except that the center bay's is the same as the lambrequins of the four vaulted bays along the qiblah wall marked B in my first diagram above. This identity of form was possible because in the courtyard arcade the piers of the center bay are wider than the others, thus narrowing the arch so that the same lambrequin could be used as in the subsidiary vaulted bays. Thus the north side of this arcade is arranged just as the arcade in front of the qiblah wall (as restored by me), assuming assimilation of the arch profiles of all the vaulted bays to the same design.

Of course it is part of the aesthetic interest of these mosques that one may view the arrangement of bays in the arcades discussed above in more than one way, just as the second example of two-color tile patterns, above, can be seen in three different ways.

Ewert traced the principle of hierarchical articulation (which takes many forms) back to earlier so-called “T plan” mosques. These mosques do not exhibit subsidiary axes of symmetry but some of them have corner bays next to the qiblah wall that are emphasized by vaulting.18 Such vaulted corner bays are first known from Fāṭimid Cairo, probably in the first version of the Mosque of al-Azhar (completed 361/972) and certainly in the Mosque of al-Ḥākim (completed 381/991).19 For the Mosque of al-Azhar the original arrangement of the bays in front of the qiblah wall can be diagrammed

B C C C C C C C C A C C C C C C C C B

or

A B B B B B B B B A B B B B B B B B A

although there is no particular reason to think that anyone thought of the corner bays as equivalent to the center bay. For the Mosque of al-Ḥākim the corresponding diagrams are

B C C C C C C C A C C C C C C C B

and

A B B B B B B B A B B B B B B B A

So far as I know no one has ever put forward an explanation for the vaulting of the corner bays based on either liturgy or the practice of prayer, and I have none myself.

The architectural significance of these arrangements is twofold. In the first place the Fāṭimids, as no one can forget, came from North Africa, so similar designs may already have existed there (although none is known). In the second place the corner domes suggest the possibility of regarding each wing of the arcade, including the center bay, separately, as a sequence of plain bays bracketed by emphasized bays. By contrast there is no particular interest in any of the bays of most other qiblah walls except for those in the center, or, on occasion, those flanking the center bay. Could this have been the aesthetic motive for vaulting the corner bays: to close the view down the qiblah wall with something more elaborate than a sequence of plain bays?

I believe Ewert was right to see the development of the wings of the qiblah arcades of Almohad mosques as beginning with the arrangements with corner domes. The corner domes were like a piece of sand in an oyster, an unfinished concept, as they stood in contrast with the long stretches of undifferentiated bays (seven or eight in the Fāṭimid examples) between them and the dome in front of the mihrab. The next step in developing this concept was to break up those stretches with additional domes, as in the two Kutubīyah mosques. The mosque at Tinmal can be seen as a reduced and thereby improved version of this design. It is the breaking up of the wings with intermediate domes that produced subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms. (A reminder: I restrict the construct of symmetry of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms to cases in which the subsidiary axes of symmetry are distinguished by some change in the design of the elements, so I disregard the trivial subsidiary axes one can find in the Fāṭimid examples—or any arcade—simply by locating the midpoint of each wing.)

The aesthetic motive for this design change, I think, was a desire to create an alternation of plain and decorated spaces.20

The use of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms in the Almohad mosques is not found in earlier western Islamic architecture; it seems to have developed particularly in response to a particular design challenge. What appears most commonly is variation in coördinate detail with reflection.

Figure 9. Great Mosque of Qayrawān, facade on courtyard.

One earlier monument deserves mention in connection with subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms. Marçais claimed that the wings of the prayer hall arcade facing the courtyard of the Great Mosque of Qayrawān, which he thought was built in 875 by the Aghlabid Ibrāhīm II (r. 261–89/875–902), possessed subsidiary axes of symmetry with three overlapping sets of elements. The central bay and the two narrow bays flanking it were one set. The two wings of the arcade, each composed of four bays of equal size, one of the narrow bays flanking the central bay, and the bay at the outer end of the arcade, were the other two sets. This analysis is incorrect, if only because the two outermost bays are narrower than the two flanking the central bay (and so do not have symmetry of reflection with them); in fact, the whole facade seen today is a relatively late reworking (at earliest 693/1294), replacing whatever arrangement existed following Ibrāhīm II's extension of the original prayer hall by two bays. There is nothing in the plan of the older parts of the prayer hall to indicate that the lateral bays of the facade on court were meant to be varied in size.21

Even so, the smaller bays seem to have been made that way out of necessity rather than from some design principle: the piers of the central dome narrow the adajcent bays of the wings and consume space without allotting any to the inner columns of these innermost bays; these columns are therefore applied to the sides of the piers, thus narrowing the arches further. Similar situations obtain at the outermost ends of the wings. The result seems not to be even an example of intentional symmetry of the late seventh/thirteenth century.

Before surveying the use of variation in coördinate detail with reflection in earlier and later western Islamic architecture it is useful to review the possibilities for symmetrical arrangements in smaller sets of elements than appear in the Almohad arcades and to distinguish the design principles of variation in coördinate detail and alternation.

A design with only a single element has no symmetry at all in the current context; a design with two elements side by side can be arranged

A B

which is not symmetric, or

A A

which need not be the result of any conscious design decision. A design with three elements side by side can be arranged

A A A

which again need not be the result of any conscious design decision, or

B A B

which is more interesting, but could be simply an alternation of two forms of the same element, or

A B C

which could be an example of variation in coördinate detail.

The reader can work out the possibilities for designs with four elements side by side. Considering several cases of five elements side by side I distinguish

C B A B C

which is an example of variation in coördinate detail with reflection, from

A B A B A

which can be seen simply as an alternation of two forms of the same element. (It is also a concise example of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms in which the sets of reflected elements overlap in the center, but the variation in coördinate detail in this case I consider not to be significant.)

Finally, to make clear this distinction,

… B A B A B A B …

I consider to be alternation and not variation in coördinate detail.

The Great Mosque of Cordoba provides early examples of variation in coördinate detail with reflection.

Figure 10. Cordoba, Great Mosque, Bāb al-Wuzarā', detail.

In the exterior gate of the Great Mosque of Cordoba known as the Bāb al-Wuzarā' (reconstructed in its present form in 241/855–56) the horseshoe arch over the doorway is composed in part of carved white stone voussoirs alternating with voussoirs constructed of red brick.22 The white voussoirs vary in decoration, as follows:

D C B A B C D

While the portal has been restored it is plausible that these voussoirs at least reflect the originals, especially as the same arrangement is seen in the other, later portals. This is an example of variation in coördinate detail with reflection.

Figure 11. Cordoba, Great Mosque, mihrab, detail.

The mosaics in the lobed arcade above the mihrab (354/965) have four different loose foliate patterns, arranged:

D C B A B C D

Of these only B lacks symmetry of reflection along its central vertical axis, and the two B's are reflections of one another along the central vertical axis of the arcade.23 Here again is an example of variation in coördinate detail with reflection.

For other parts of the Great Mosque of Cordoba see Appendix B.24

Three mosques of the period immediately preceding the trio of Almohad mosques discussed above, and in the same region, do not exhibit subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms. To support that observation I shall review them briefly.

The partly Almoravid Great Mosque of Algiers (about 490/1097), which I include here because it was also considered by Ewert, has varied arch profiles but is not an example of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms.25 The arcade next to the qiblah wall and another lateral arcade two bays farther away both exhibit the following sequence of profiles:

C C C C B A B C C C [C]

(I restore the rightmost C form on the basis of arch forms farther south in this nave). This is not a case of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms, although it is an example of hierarchical articulation and of a willingness to use multiple profiles within a single arcade.

The Mosque of the Qarawiyīn in Fās is largely the work of the Almoravid amīr ʿAlī b. Yūsuf (r. 500–37/1106–42) between 528 and 537 (1134–42).26 The mosque has a profusion of arch profiles in addition to its varied domes, but there do not seem to be any subsidiary axes of symmetry in the arcades or anywhere else.

Figure 12. Tilimsān, Great Mosque, courtyard, prayer hall facade.

The courtyard facade of the prayer hall of the Great Mosque of Tilimsān presents something of a puzzle.27 The dome in front of the mihrab is dated by inscription to 530/1135 and originally bore the name of the Almoravid amīr ʿAlī b. Yūsuf. Another inscription nearby is dated to 533/1138. Its present state is clearly not the original one. According to Lucien Golvin, who attributes it to an Almohad reconstruction, the arcade of which the present facade is a part continues across the lateral aisles on either side of the courtyard; if one includes the two bays to the west of the present courtyard the arrangement of arch profiles is: a central large lambrequin arch; then on either side at roughly the same, lower height, a round horseshoe arch, a simpler lambrequin, and a pointed horseshoe arch:

D C B A B C D

which clearly indicates that the courtyard has been encroached upon by the addition of lateral aisles. However, Golvin's elevation drawing also shows a lambrequin arch in the bay to the east of this arrangement, with two taller round horseshoe arches in the bays to its east, and on the west, two additional round horseshoe arches of the same height as those marked B in the diagram above. These irregularities have not been resolved satisfactorily, but I cannot see how the facade can be imagined to have been wider than seven bays with any aesthetically plausible arrangement of arch profiles.28 As it is, the seven bay arrangement is an example of variation in coördinate detail with reflection.

Returning briefly to the Almohads, Basset and Terrasse recorded painted foliate decoration on the exterior of the minaret of the Kutubīyah mosque, in the blind arcades.29 It is particularly interesting because the blind arcades themselves exhibit no variation in arch forms. The painted decoration exhibits a tendency toward variation in coördinate detail with reflection: in the seven lobes of a lobed arch the arrangement is:

D C B A B C D

(in fig. 51, 53, and 54; also fig. 37, interpolating missing ornament; and probably in fig. 50, where the lowest lobes are both missing). The arrangement

C B B A B B C

also occurs (in fig. 49 and fig 39, interpolating missing ornament in the latter).30

The Qubbah al-Barūdiyīn stands in what is thought to have been the latrine of the Great Mosque of ʿAlī ibn Yūsuf (500–37/1106–1143) in Marrakesh and is dated by inscription to the reign of that Almoravid amīr.31 The structure bearing the dome is rectangular, and on the exterior of its two long sides the internal zone of transition is masked by dwarf arcades. Each arcade, of five arches, has a lobed arch in the center, flanked by two pointed horseshoe arches, with arches of an unusual form resembling loopholes at the ends:

C B A B C

The short sides have only three arches in the corresponding arcades, a central lobed arch as on the long sides and the unusually shaped arches:

C A C

The choice of arch profiles in the long and short sides indicates that the center and outer elements were seen as primary in the long side, so that the B's on the long side are in a way fillers.

This little monument is nicely connects Spanish architecture, with its use of variation in coördinate detail with reflection, and the Almohad monuments discussed above. Almoravid architecture must stem ultimately from Spanish sources, and here a design principle that appears as early as one could wish in the surviving corpus of Spanish Islamic architecture (in the Bāb al-Wuzarā' of the Great Mosque of Cordoba) occurs in the great mosque of the city founded by the Almoravids and taken by the Almohads in 1147.

In the later sixth/twelfth and the seventh/thirteenth centuries the extant architectural evidence for the use of variation in coördinate detail with reflection in the western Islamic world is thin. I give three examples from the first half of the eighth/fourteenth century.

The Madrasah al-ʿAttarīn in Fās, completed in 725/1325, provides an excellent example of the complexity that Mārinid architectural decoration could attain.32 I lack the photographic material, time, and inclination to produce a full survey of the ʿAttarīn's various symmetries and constructs of symmetry.33 In Appendix B I present the results of an analysis of the lateral arcades of the courtyard. Here I am concerned with the qiblah wall of the mosque of the madrasah. The building appears to have been restored in many places, possibly first in 1916, as a restoration of the Bū ʿInānīyah Madrasah of that date is mentioned by Albert Bel in 1919; however the photographs he published of the ʿAttarīn certainly do not show a completely restored building.34 Georges Marçais published a prerestoration photograph of the southwest corner of the courtyard which shows it in poor condition but very largely preserved in the areas of concern here.35 The initial restoration, at any event, was completed before the photographs published by Charles Terrasse in 1927 were taken, and it had been restored yet again before my photographs were made.36 The results seem to have been faithful to the original.

The overall design of the ʿAttarīn's qiblah wall, with its blind side arches, would be worth studying in detail, but not here; I shall forego a full description and call out only those elements that are of the same size and shape and number three or more.

Figure 13. Fās, Madrasah al-ʿAttarīn, mosque, qiblah wall and upper portion of mihrab.

Figure 14. Fās, Madrasah al-ʿAttarīn, mosque, qiblah wall, upper part, with detail.

From bottom to top, these are [Q1] the pseudovoussoirs of the mihrab's frontal arch; [Q2] the segments of the mihrab's niche head; [Q3] the three blind arches above the mihrab niche surround and the four panels of arabesque (inside panels) and inscriptions (outside panels) flanking and between them; [Q4] the spandrels of those blind arches; [Q5] the series of octagrams above the large blind side arches, which continue a frieze running around the entire room; [Q6] the lobed blind arches above that frieze and the narrow arches between them, also continuing a frieze that runs around the entire room; and [Q7] the blind arches and windows at the top of the wall decoration, again continuing a frieze that runs around the entire room. I have insufficient photographic evidence to document the other walls or to be sure of all of Q5, Q6, and Q7 on the qiblah wall, but the first four sets of elements are interesting enough.

In the case of Q1 every other element is raised, but this does not create additional complexity of symmetry, as the designs of the raised and (conversely) recessed voussoirs always occur on one but not the other. The designs are adapted to the changing outline of voussoirs, a detail I ignore here. There appears to have been some loss and restoration, which makes photographic study difficult, but I distinguish (A) an arabesque of comparatively thick vegetal elements, on raised voussoirs; (B) an arabesque of thinner vegetal elements, forming two and a half round forms, counting from the bottom, and terminating at the top in two ovals pointing to the upper corners of recessed voussoirs; (C) what is probably an inscription, the upper parts of which form lobed arches, on raised voussoirs; and (D) an arabesque of thin vegetal forms the uppermost part of which is a round form enclosing a fleur-de-lis, on recessed voussoirs. The center voussoir is indicated in bold type in my diagram:

D C B A D C B A D C B A D C B A B C D A B C D A B C D A B C D

or, more simply, four sets of the series ABCD mirrored by four sets of the series DCBA, overlapping at the central voussoir, an A. This is an elaboration of the principle of variation in coördinate detail with reflection which I do not feel compelled to invent a name for yet (compare the circular repetition of four ornamental variants in the dome in front of the mihrab of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, below). I believe the same arrangement can be seen in the the pseudovoussoirs of the frontal arch of the mihrab of the Great Mosque of Tāzā (probably 691/1292), to cite but one other example.37

There are only seven elements in Q2: (A) a reflected and interlaced inscription the uprights of which form lobed arches; (B) an arabesque; (C) another but different inscription the uprights of which form lobed arches and other forms unnecessary to detail here; and (D) an arabesque much like B but not the same. The arrangement is:

D C B A B C D

This is an example of variation in coördinate detail with reflection.

As an experiment in analysis I have analyzed Q3, which is not really composed of coördinate forms, as having two kinds of elements. The blind arches are indicated by capital letters and the rectangular panels by lower-case letters:

d C b A b C d

If one conflates the differently shaped elements the analysis is:

D C B A B C D

which exemplifies the same sort of thinking behind variation in coördinate detail with reflection. I think this is the correct way of seeing the set of elements, as separating the differently shaped elements produces

C A C

d b b d

which is dull. However, it is worth repeating that the possibility of seeing a design in various ways is part of what makes playing around with symmetry interesting, as it is the mark of a good work of art that it repays continued contemplation.

In Q4 I believe the intention was to present

A A A A A A

but that there has been some variation introduced by restoration.

Without analyzing it in detail, I think it worthwhile remarking that Q6 presents the same sort of alternation of subelements as Q3, except that the narrow arches all seem to be filled with the same design. They might have been painted in alternating colors or varied otherwise. Among the wider blind arches arabesques (including the central element) seemingly of more than one design alternate with reflected and interlaced inscriptions, again seemingly of more than one design. This is the sort of alternation shown by Q1. As the frieze (I think) runs around the entire room it deserves documenting in its entirety.

Figure 15. Mosque of Abū Madyan, porch, center and right side.

In the porch of the Mosque of Abū Madyan, in Tilimsān (739/1339), built by the Mārinid sultan Abū'l-Ḥasan,38 on the lateral walls above the doorways there are friezes of five arched fields, employing three different stucco patterns, arranged in the order:

C B A B C

Figure 16. Mosque of Abū Madyan, porch, left side.

This is an abbreviated example of variation in coördinate detail with reflection, which in turn is reflected on the opposite wall. This building's stucco decoration is of the highest quality, and the distribution of patterns in the interior deserves study.

Above, I pointed out variation in coördinate detail with reflection in the capitals of the north arcade of the Court of the Myrtles. There are other occurrences of variation in coördinate detail with reflection and similar arrangements in the Alhambra. Here is one sample.

Figure 17. Alhambra, Cuarto Dorado, south side of courtyard and detail of doorway to the Court of the Myrtles.

In the south side of the courtyard of the Cuarto Dorado (attributed to the Naṣrid sultan Yūsuf I, 733–55/1333–5439) the stucco pseudovoussoirs of the eastern door (leading to the Court of the Myrtles) are arranged

H G F E D C B A B C D E F G H

I believe that the pseudovoussoirs of the other door are arranged similarly, but with a different sequence of patterns. The top two-thirds of both sets appear to be original.40

Figure 18. Court of the Lions, view to east from northwest corner and the Lion Fountain with the center of the south facade.

And so at last I return to the Court of the Lions. Although restored many times, it seems to preserve its original stucco decoration—or at least its mid-nineteenth-century stucco decoration—almost entirely. The columns and capitals are original, too, though perhaps not in their original positions; they have been catalogued and their disposition analyzed by Purificación Marinetto Sánchez, who concludes that unlike other parts of the Alhambra, in the Court of the Lions there is no clear symmetrical arrangement of the capital types with respect to any axis, except for the east facade, a fact she attributes to repeated repair of the arcades.41

The arrangement and symmetries of the Court of the Lions have been analyzed variously.42 Here I confine myself to the courtyard and pavilion facades, leaving much else aside.

Antonio Fernández-Puertas has proposed a reconstruction of the procedure used to lay out the plan of the courtyard. While he arrives at his understanding of the composition differently than I do, and with some small differences in result, Fernández-Puertas recognizes the same three zones (my terminology), as does Sánchez.43

The western zone is composed of the three bays on the west end, including the west pavilion, the two sections of the west facade on either side of it, and the three westernmost bays of the north and south facades. The eastern zone is composed of the the corresponding elements on the east end, and the central zone is everything in between, that is, the center eleven bays of the north and south facades. The center bays in both the north and south facades, which lead to the Hall of the Two Sisters and the Hall of the Abencerrages respectively, are wider than all the others. The other ten bays are of approximately equal width (from column to column, taking the inner columns in the case of doubled columns), and the bays of the western and eastern zones vary in width but are generally smaller. Given the number of intercolumnar spaces in the three zones, it would not have been possible for the columns of the western and eastern zones to be spaced like those of the central zone. The consistent height of the wooden fascia above the stucco decoration, called alicer by Fernández-Puertas,44 is maintained by employing different arch profiles in the western and eastern zones from those in the central zone and by filling the space below it in all but the two widest bays with fields of stucco decoration.

To review: both the north and south facades consist of portions of all three zones. On either end of each facade is a three-bay section corresponding to the pavilions, in the center is a large arch on the axis of the large domed chambers beyond the arcades, and in between, in each wing of the facade, is a unit of five bays.

This organization of parts of is clearly indicated by the arrangement of inscription bands framing groups of bays and the patterns of the stucco fields above their arches.

A single continuous inscription band runs around the courtyard and its pavilions directly below the wooden fascia. It is interrupted only by square interstitial motifs where it intersects vertical inscription bands framing groups of bays and at the outer corners of the pavilions. The intended framing effect of these vertical bands is evident from the choice of baseline for the script they contain. The large center bays in the north and south facades are framed by vertical inscription bands in which the script baseline is on the inner side, just as though the inscription actually ran continuously around the framed bay. The three end bays of the north and south facades, belonging to the western and eastern zones, are framed similarly. There are no such vertical inscription bands on the east and west facades (by which I mean the facades of the arcades on either side of the pavilions).

On all sides of both pavilions the decoration running continuously above the three arches is framed with inscription bands meeting at square interstitial motifs; the top inscription band does not run continuously, and the outer corners are filled with vertical rectangular fields of decoration on both faces, with thin engaged colonnettes at the outer corners.

Above the arches of the arcades are fields of carved stucco; above the columns, except for the space taken up by the vertical inscription bands, are vertical rectangular fields of decoration, as on the pavilions.

The spandrels of the two large bays in the center of the north and south facades are filled identically, with rosettes on a foliate background. The patterns of the stucco in the fields above the arches are based on grids of interlaced lambrequin arches, called sebka by Fernández-Puertas.45

In the eastern and western zones, in each of the four three-bay sections at the ends of the north and south facades the pattern of the decoration above the arches is the same. The same pattern also appears on the face of the west pavilion (the side facing the Lion Fountain), but not on its sides, which share a similar but noticeably different pattern. In the case of the east pavilion the sides also share a pattern different from that on the face, and it also differs from those of the three-bay sections opposite it and the west pavilion.46 So while these three-bay sections of the north and south facades are clearly intended to be seen as corresponding to the pavilions, they are not, in detail, reflections of it.

In the central zone, in each of the four five-bay units of the south and north facades the stucco patterns of the fields above the arches are arranged:

C B A B C

and the same patterns are used for the A's, B's, and C's in all four units.

A complication is added to this analysis, though, by the use of both single and doubled columns. Like the center arch of both the north and south facades, the center arch of each of the five-bay units is supported by two pairs of columns, as are the outer ends of the arches of the outermost bays of these units. The remaining columns are single. This arrangement has symmetry of reflection with respect to the central axis of the center bay of the five-bay unit, but causes the bays to vary in width by the width of the extra columns. The width of the fields above the bays is kept equal by increasing the width of the vertical rectangle over the doubled columns.

Stretching a point, I consider the bays of the five-bay units to be coördinate forms. Each of these units is thus an example of variation in coördinate detail with reflection.

Figure 19. Court of the Lions, west half of south facade and its five-bay unit.

Figure 20. Court of the Lions, east portion of north facade, stucco patterns in center, flanking, and outer bays of five-bay unit.

Figure 21. Court of the Lions, east (left) and west (right) pavilions.

Except for the three end bays of the north and south facades and the pavilions, where the decoration above the arches runs continuously, the vertical rectangular fields directly above the columns are decorated with flat carved ornament, also based on interlaced lambrequins. Their patterns are varied: in both the north and south facades the arrangement seems to be

D B C C B A A B C C B D

but in the pavilions and the east and west facades, which are arranged differently from each other,47 different patterns seem to be used, with symmetry of reflection with respect to the center of the pavilion on the west but not on the east.

Above the columns of the three end bays of the north and south facades and the exterior faces of the pavilions are imposts with engaged dwarf colonnettes at their corners; the space in between is filled with a foliate arabesque pattern, which I believe is the same in all cases.

Figure 22. Court of the Lions, west end of south facade.

Figure 23. Court of the Lions, west facade, south and north portions.

Figure 24. Court of the Lions, east facade, south portion.

Figure 25. Court of the Lions, east facade, north and south portions.

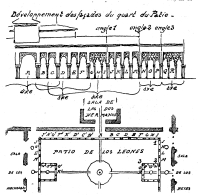

Figure 26. Court of the Lions, diagram by Georges Marçais.48

Georges Marçais analyzed the composition of the Court of the Lions in terms of organes de liaison. His key for analysis was the grouping of columns and he thought it meaningful to regard the bays of the facades as a single series, running through the corners and around the pavilions. He saw that each set of three end bays of the north and south facades corresponded to a side of one of the pavilions (an élément de rappel). He thought that the north side of the east facade (Marçais's J, K, L, and M) reproduced symmetrically a stretch of the east wing of the north facade (F, E, D, and C) on the basis of the grouping of columns. Finally, he sketched out a set of overlapping axes.

The general correspondence of the four sets of three end bays in the north and south facades with the four north and south sides of the two pavilions is certain, although as pointed out above the stucco patterns do not match.

The analysis of the bays of the courtyard facades as a single series, however, produces no valid results,49 as the four bays of the east facade (J, K, L, and M) do not match the four bays Marçais selected from the north facade in width or stucco patterns. Marçais completely missed the grouping of bays by means of vertical inscription bands and the symmetry of reflection of the stucco patterns within the groups of five bays in the wings of the north and south facades (in his diagram, B, C, D, E, and F).

Consequently the sets of bays Marçais chose as overlapping symmetrical sets (organes de liaison) are mostly trivial or nonsensical. From left to right in the diagram, the first set (A, B, B', C, and C') cuts the next set in two arbitrarily (and its symmetry of reflection is trivial given that the entire facade has symmetry of reflection with respect to its central axis). The next set is the group of five bays already identified as a case of variation in coördinate detail with reflection but it overlaps nothing, as the vertical inscription band separates it from the center bay and the following set (C through M) has no symmetry of reflection because of the differences already pointed out between the two outer sets of four bays. Finally, the last two sets of three bays, on the side and face of the eastern pavilion, do indeed possess symmetry of reflection, but they overlap nothing.

In short, Marçais failed to prove his point, there are no organes de liaison in the Court of the Lions due to the lack of overlapping, and unfolding the facades as if they ran continuously around corners does not uncover any aspect of their design.

While there are no overlapping axes of symmetry of reflection in the Court of the Lions, in both the Court of the Lions and the Court of the Myrtles there are examples of subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms; for convenience I shall group both that construct of symmetry and variation in coördinate detail with reflection under the rubric “western symmetries”.

There is a distinct difference between the subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms of the Alhambra and those of the Almohad mosques: in both the Court of the Lions and the Court of the Myrtles the spans of bays that exhibit symmetry of reflection with respect to the subsidiary axes are disjunct, rather than overlapping in the center of the overall arrangement.

While the variation in coördinate detail with reflection of the Cuarto Dorado courtyard is more elaborate than seen in earlier architecture it involves the same overlapping in the center. The variation in coördinate detail with reflection of the capitals of the Court of the Myrtles is again (necessarily) disjunct.

Furthermore, the architectural elements of these displays of symmetry often differ from those of earlier examples. In the sixth/twelfth-century Tinmal mosque the means by which the bays are differentiated for the purpose of exhibiting a construct of symmetry is the varying profiles of their arches. In the eighth/fourteenth-century Alhambra what is varied is the stucco patterns in the fields above the arches. The application of variation in coördinate detail with reflection to capitals is unique to the Court of the Myrtles, so far as I have yet found. And while variation in coördinate detail with reflection occurs in sets of stucco pseudovoussoirs in the Cuarto Dorado, as in previous mihrabs, the pseudovoussoirs of the mihrab of the mosque of the Mexuar have a significantly different, though related, arrangement.50

What these changes reveal about the Alhambra is not entirely clear to me; I hope others more familiar with Naṣrid art may be able to say. But I wonder if they do not show that the use of these western symmetries in the Alhambra is not entirely a matter of continuity, but at least partly of revival or retrospection, if not in fact archaism.

1. A common solution to turning the corner in architecture is to supply a distinct element to occupy the corner; these are rare in carpets, which shows that the borders are conceived as running continuously through the corner turn.

2. Marçais, “Remarques sur l'esthétique musulmane” Annales de l'Institut d'Études Orientales, Algiers, v. 4, 1938, pp. 55–71; the article is devoted to a discussion of devices intended to secure the unity of the various parts of an ensemble (“artifices destinés à assurer la liaison entre les diverse parties d'un ensemble”, p. 56; his remarks on the Court of the Lions are on pp. 64–69, illustrated by fig. 6.

3. Darío Cabanelas and Antonio Fernández-Puertas, “Los poemas de las tacas del arco de acceso a la Sala de la Barca”, Cuadernos de la Alhambra, v. 19–20, 1984, pp. 61–149, p. 147, provide the date 1367 for the critical event, the fall of Algeciras to Muḥammad V, but the correct date appears to be two years later, given in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. s.v. “Naṣrids”.

4. Images in Time: A Century of Photographs at the Alhambra, 1840–1940, Granada, 2003, p. 15.

5. I have and would prefer to continue to call this principle “unity in variety”, but I have come to think that that phrase is hopelessly compromised: it has been used too variously to hold precision, as well as having theological implications I do not intend. This design principle is common in all artistic traditions, but it comes to the fore in the relatively aniconic tradition of Islamic art.

6. The external facade of the Tīmūrid madrasah at Khargird, Iran, appears in photographs to have subsidiary axes of symmetry of reflection in a series of coördinate forms but the wings, each of three bays, lack symmetry of reflection because in each the outermost bay and the bay flanking the portal are not the same width or depth.

7. Sanctuaires et Forteresses Almohades, Paris, 1932, pp. 24–28.

8. Forschungen zur almohadischen Moschee, v. 1, Vorstufen (Madrider Beiträge, v. 9), Mainz, 1981, and v. 2, Die Moschee von Tinmal (Madrider Beiträge, v. 10), 2 v., Mainz, 1984. The subsidiary axes of symmetry are alluded to in v. 2, p. 133. Ewert reviewed his ideas on western Islamic architecture in “The Architectural Heritage of Islamic Spain in North Africa”, Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain, ed. Jerrilynn D. Dodds, N.Y., 1992, pp. 84–95, in which he remarks that the northern arcade, shown on some of the plans he and Wisshak published, was never built (p. 89).

9. As Ewert pointed out, v. 2, p. 32, they had already noted the “hierarchische Disposition der Arkadenboegen” in Basset and Terrasse, op. cit., p. 55 and fig. 12.

10. L'art hispano-mauresque des origines au XIIIe siècle, Paris, 1932, pp. 330–31.

11. Ewert, op. cit., v. 1; the date from p. 3, n. 28.

12. Basset and Terrasse, op. cit., pl. 15 and fig. 34 and 35 are the earliest photographs I know of; cf. Jacques Meunié and Henri Terrasse, Recherches Archéologiques à Marrakech, Paris, 1952, pl. 1, 25–33; see pp. 38–42 for a discussion of these remains.

13. I disregard here an irregularity in the layout of the plan: the naves next to the east and west walls are narrower (3.95 m. according to Ewert's plan, v. 1, fig. 5) than the other naves, of which the center one is 5.62 m., the rest 4.06–4.16 m., and the two flanking the center nave 4.34 and 4.35 m. It is apparent that the outermost naves are narrower than other naves by the amount the naves flanking the center nave are wider than all of the others except the center nave. I suspect that this difference accomodates a miscalculation made in laying out the foundations of the machinery that raised and lowered the maqṣūrah (Meunié and Terrasse, op. cit., pp. 45–50) and discovered too late to remedy it: the naves flanking the center one were made wider than the intended width to accomodate the error and the difference was taken up in the outside two naves. The planned width was 4.10 m. or a bit more, and the plan was adhered to (insteading of distributing the error over all the naves) because the planned width matched the planned depth of the bays, which are 4.00–4.19 m. in the prayer hall; for some reason the bays of the naves flanking the courtyard are a bit deeper. In the second Kutubīyah mosque all the naves except the center one were planned to be about 4.32 m. wide (the average of the actual construction) and the error made during construction of the first Kutubīyah mosque was avoided. Cf. Ewert, op. cit., v. 1, p. 4.

Further on the metrology of Almohad mosques, see Christian Ewert, “Die Moschee von Mértola”, Madrider Mitteilungen, v. 14, 1973, pp. 217–46.

14. Op. cit., pp. 33–35, fig. 13. For the width of the bays see the previous note, and Ewert, op. cit. v. 1, fig. 5 for measurements and p. 4 for an analysis of the plan different from mine.

15. Apparently not on the basis of the stumps of piers excavated, pl. 22 and 28, discussed pp. 35–36, but because of the stubs of arches in the qiblah wall and the fact that the corresponding bays along the qiblah wall of the second Kutubīyah are also vaulted.

16. Ewert, op. cit., v. 1, p. 3, n. 28.

17. Basset and Terrasse, op. cit., pp. 84–87, fig. 26, pl. 13 for the general layout; fig. 70 and pl. 21 for the arches; Ewert, op. cit., v. 1, pp. 106–07 and fig. 5, with arch profiles marked; Basilio Pavon Maldonado, Estudios sobre la Alhambra, 2 v., Granada, 1975–77, v. 2, pl. 7 for a view along the qiblah wall. There seems to be no pattern in the distribution of capital types as catalogued by Ewert, Forschungen zur almohadischen Moschee, IV. Die Kapitelle der Kutubīya-Moschee in Marrakesch und der Moschee von Tinmal (Madrider Beiträge, v. 16), Mainz, 1991.

18. This nonhierarchical emphasis Ewert accounted for by seeing the combination of the qiblah aisle and the two extreme side aisles of the prayer hall as a kind of U-shaped ambulatory, op. cit., v. 1, p. 111. For a summary of this view and the inferences Ewert drew from it, see “The Mosque of Tinmal (Morocco) and some New Aspects of Islamic Architectural Typology”, Proceedings of the British Academy, v. 72, 1986, pp. 115–48. While it is true that at Tinmal the extreme side aisles are wider than all the other aisles perpendicular to the qiblah except the central aisle, and that their width matches the depth of the aisle in front of the qiblah wall, this was certainly done so that the end bays of the qiblah aisle would be (nearly) square in plan so as to support a dome circular in plan. The widths of the axial, qiblah, and extreme side aisles in “T plan” mosques must be (nearly) the same in order to create square bays for vaulting; if not, various adjustments to the shape of piers and the plan of the corner and center bays were employed to get things right. There is no reason I know of to think that the extreme side aisles had any particular significance or use.

19. Al-Azhar: The Muslim Architecture of Egypt, Oxford, 1952, v. 1, pp. 36, 59; Creswell's reconstruction of two corner domes is well reasoned and very likely but not absolutely certain. Al-Ḥākim: The Muslim Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, p. 81.

20. The so-called Qaṣbah Mosque in Marrakesh (Almohad, 580–86/1185–90) has an unusual plan that seems to have determined the arrangement of the arch shapes in the arcade in front of the qiblah:

B C C C C A C C C C B(the right wing partly reconstructed), Christian Ewert and Jens-Peter Wisshak, “Forschungen zur Almohadischen Moschee, III. Die Qaṣba-Moschee in Marrakesch”, Madrider Mitteilungen, v. 28, 1987, pp. 179–211. Also to be noted is the mihrab of the former Great Mosque in Almeria, in which the arch forms seem to have been arranged

C A B A B A Caccording to fig. 8 in Christian Ewert, “Der Miḥrāb der Haupmoschee von Almería”, Madrider Mitteilungen, v. 13, 1972, pp. 286–344; one must mentally complete the C's, which are partly cut away by the arch of the entry to the small chamber.

21. Marçais, “Remarques sur l'esthétique musulmane” pp. 62–64 and fig. 5; Creswell, op. cit., pp. 208ff (measuring the plan, fig. 180, gives the difference in bay width); Alexandre Lézine, Architecture de l'Ifriqiya: Recherches sur les monuments Aghlabides, Paris 1966, p. 19.

22. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture, 2nd ed., Oxford, 1969 v. 2, p. 140; also on the portal Klaus Brisch, “Zum Bāb al-Wuzarā' (Puerta de San Esteban) der Hauptmoschee von Córdoba”, Studies in Islamic Art and Architecture In Honour of Professor K.A.C. Creswell, pp. 30–48. For additional bibliography see Jerrilynn D. Dodds, Architecture and Ideology in Early Medieval Spain, University Park, Pa., 1989, pp. 148–49, n. 25 to p. 52.

23. Discussed by Henri Stern, Les mosaïques de la grand mosquée de Cordoue (Madrider Forschungen, v. 11, 1976), pp. 18–21; he seems to have thought the mosaic here mostly original and noted the symmetry of reflection. There is a very good photograph in Marianne Barrucand and Achim Bednorz, Moorish Architecture in Andalusia, Köln, 1992, p. 79. There is certainly the possibility that the decoration of this frieze has been distorted by restoration.

24. A completely different construct of symmetry can be seen in the so-called Salón Rico of Madīnah al-Zahrā' near Cordoba. One can study it in the illustrations to Natascha Kubisch, “Der geometrische Dekor des Reichen Saales von Madīnat az-Zahrā': Eine Untersuchung zur spanisch-islamischen Ornamentik”, Madrider Mitteilungen, v. 38, 1997, pp. 300–63, although Kubisch, whose interest lies elsewhere, does not remark on it. In some of the enframing panels (the so-called alfizes) of the arches of the doorways there are frameworks enclosing inclusions, and in one (fig. 4 b, pl. 52 a, b) the motifs of the inclusions are alternated pairwise on the sides:

… B B A A B B A AOne might expect the pairwise arrangement to turn 90° at the upper corners, but instead the arrangement is:

A A A A A A A … B B B B B B B … A A B B A A …as if the entire U-shaped panel had been cut from a piece of cloth (cf. pl. 54 a, 56, where a similar approach has been taken). I do not know whether this arrangement is the result of decisions made during restoration or can be documented from the fragments found in excavation.

25. Ewert, op. cit., v. 1, pp. 28–29 and fig. 17, with arch profiles marked.

26. Henri Terrase, La mosquée al-Qaraouiyin a Fès, Paris, 1968.

27. For the date see William and Georges Marçais Les monuments arabes de Tlemcen, Paris, 1903, pp. 140–41.

28. Lucien Golvin, “Quelques réflexions sur la Grande Mosquée de Tlemcen”, Revue de la occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, v. 1, 1966, pp. 81–90.

29. Basset and Terrasse, op. cit., pp. 107–82; as they observe, p. 106, there is no way of telling to which building campaign this decoration belongs.

30. There is also

C C B A C C C(pl. 20) and there are several indeterminate cases: fig. 45 (half missing) and fig. 48 (nearly half gone).

31. Boris Maslow, “La Qubba Barūdiyyīn à Marrākuš”, Al-Andalus, v. 13, 1948, pp. 180–85; Jacques Meunié and Henri Terrasse, Nouvelles Recherches Archéologiques à Marrakech, Paris, 1957; for the date pp. 50–51; 1117 is possibly the most likely date for the inscription. The original state of the mosque itself has apparently been lost otherwise.

32. Albert Bel, Inscriptions arabes de Fès, Paris, 1919, pp. 168–229, with a handful of photographs; the contents originally appeared as a series of articles in the Journal Asiatique.

33. I base this analysis on published photographs, cited below, and photographic slides I took in 1985; as Fās is the only place in the world where I have been assaulted for not hiring a tour guide I am disinclined to return.

34. Bel, op. cit., p. 280; photographs of the ʿAttarīn fig. 32–43.

35. Georges Marçais, L'Architecture musulmane d'occident, Paris, 1954, p. 344.

36. Terrasse, Médersas du Maroc, Paris, n.d., the foreword dated 1927; pl. 24–33.

37. Terrasse, La grande mosqueée de Taza, pl. 48–52; see p. 40 for other examples of the type.

38. Georges Marçais, L'Architecture musulmane d'occident, p. 276.

39. Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., s.v. “Gharnāṭa”.

40. Images in Time, p. 171, a photograph of ca. 1865 (or 1875, p. 166), before the restoration shown p. 172, a photograph of ca. 1890.

41. Images in Time, passim for old photographs; for the capitals, see Los capiteles del Palacio de los Leones en la Alhambra, Granada, 1996, pp. 175, 178, and pl. 2; for documentation of the repairs, pp. 180–83. I believe that Marinetto Sánchez may have distinguished more capital types than the builders did, but I have not been successful in finding a symmetrical solution by simplifying her typology. However, in all the arcades and the pavilions taken together Marinetto Sánchez's types occur in numbers divisible by two with only two exceptions (groups of five), and groups of two, four, and eight predominate. This is a strong indication that the capitals were originally produced and hence placed pairwise, and thus probably with symmetry of reflection.

The typology and symmetries of the woodwork of the ceilings and related architectural members of the Court of the Lions have been studied by Jose Maria Velasco Gomez, “Estructura original de elementos ligneos en el Patio de los Leones”, Cuadernos de la Alhambra, v. 28, 1992, pp. 199–229; note especially the diagrams fig. 1 and 2.

42. One example among many: Basilio Pavón Maldonado, “Metrología y proporciones en el Patio de les Leones de la Alhambra. Nueva interpretación o teoría del mismo”, Cuadernos de la Alhambra, v. 36, 2000, pp. 9–33.

43. Fernández-Puertas, The Alhambra, I. From the Ninth Century to Yūsuf I (1354) (no more published), London, 1997, pp. 52–76; Sánchez, p. 179.

44. Op. cit., p. 72.

45. Op. cit., p. 96.

46. For the extra tier of stucco above the wooden frieze in the west pavilion see Fernández-Puertas, op. cit., pp. 74–75.

47. Fernández-Puertas explains the different arrangements of the east and west facades thus: “This different alignment [of columns] prevented the columns from blocking light unnecessarily from these inner rooms [the Hall of the Kings on the east and the Hall of the Mozarabs on the west], and allowed an open view to anyone standing in the patio or the rooms, while also enabling people to enter and leave these rooms without impediment” (op. cit., p. 69). Reasonable as this sounds, a glance at his plan, fig. 54, shows that the arrangement of the west facade would have been just as suitable for the east facade as its actual arrangement is.

48. “Remarques sur l'esthétique musulmane”, fig. 6.

49. As Fernández-Puertas points out, op. cit., p. 72, n. 12.

50. In the mihrab of the mosque of the Mexuar, built by Muḥammad V before 1362 (Fernández-Puertas, op. cit., pp. 110–11), the stucco pseudovoussoirs of the mihrab's arch are arranged:

B C B C B C B C B C B C B A B C B C B C B C B C B C Bwith some adjustments to the patterns in the lower four or five tiers due to compression of the space available. As there are thirteen pseudovoussoirs on either side of the central pseudovoussoir and their patterns alternate regularly, there is also a subsidiary axis of symmetry of reflection on each side in the fourth B, but it is not distinguished.