The Carved Stone Ornament of the Mosque of al-Ḥākim

by Terry Allen

Full Table of Contents

Chapter Nine. Ornamented Inscriptions

The inscriptions of the Mosque of al-Ḥākim are part of its carved stone

ornament, although both Arabic script and its freely distributed

decoration

are inherently unlike the generally repeating patterns that make up most

of the mosque's ornament.

Some of the inscriptions

include foliate ornament growing from the letters, making Arabic

script here

another category of design (along with geometry) with which

foliate elements are integrated.

Below is a list of original

Fāṭimid carved stone inscriptions on the Mosque of al-Ḥākim.

On the main entrance, northeast side, at the southeast end, fragments

not in their original position, and unornamented (see

Chapter One, The Main Entrance Frieze and the Palmette Frieze of the Northern Minaret).

In the main entrance, at the back of the entrance passage,

on a plaque, naming al-Ḥākim

(lost, see Creswell, Muslim

Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, p. 71, with bibliography;

there is an 1838 engraving of it).

Above the entrance to the staircase of northern minaret,

ornamented with

a foliate stem running across what appears to be the entire

description

(Flury, op. cit., pl. 24, 1, same as

Creswell, Muslim

Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, fig. 33, pl. 23, a;

see also Flury, pl. 24, 3, same as Creswell,

pl. 23, d), about 1.3 m. wide.147

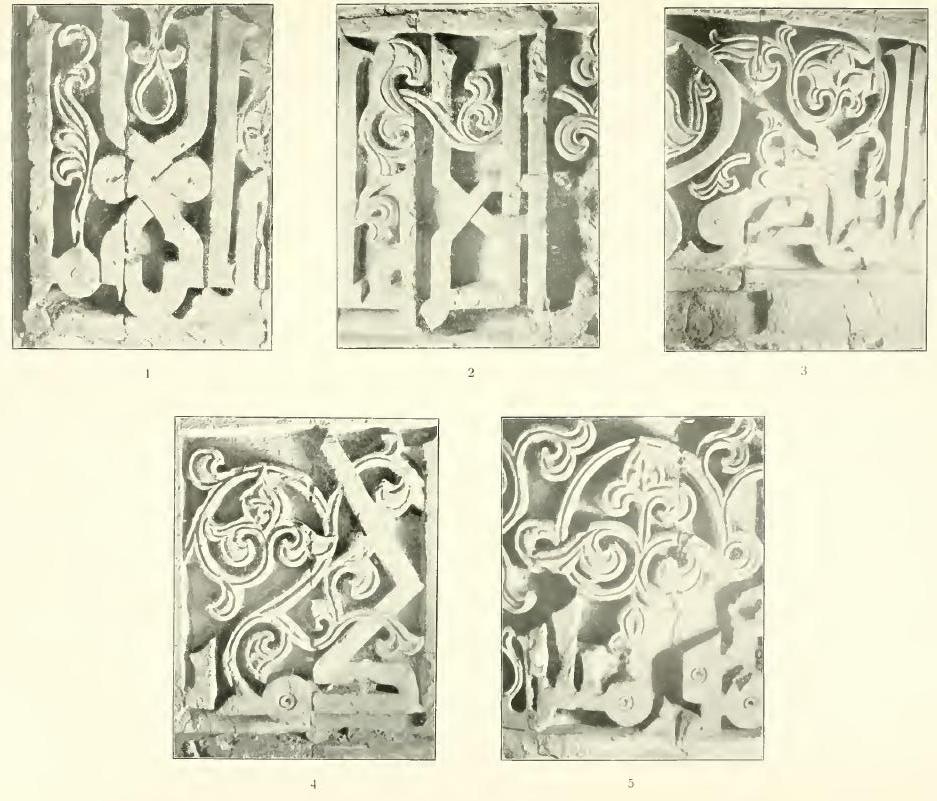

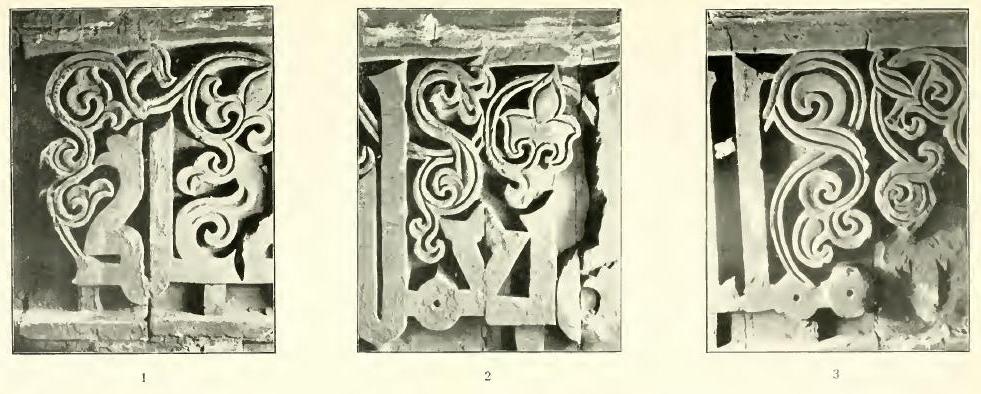

Figure 92. Inscription

above the entrance to the staircase of northern minaret;

Flury, Ornamente, pl. 24, 1.

|

On the socle of the northern minaret, a medallion

with the word Allāh, unornamented; see

“The Medallions of the Socle of the

Northern Minaret” and Figure 64.

In the surviving medallion of the second register of the

cylindrical section of the northern

minaret, a very lightly ornamented inscription in the circular frame

and an unornamented inscription in the center; see

“The Medallions of the Second Register of the Northern

Minaret” and

Figure 65.

In the frames of the blind windows of the third register

of the cylindrical section of the northern minaret.

For the unornamented inscriptions of the window facing north see

“The Screen of the Window Facing North” and

Figure 47; there are foliate forms in the

corners of the frame. For the window facing west see

“The Screen of the Window Facing West” and

Figure 48; this inscription is

lightly ornamented and shares the corner forms of the window

facing north.

In the fourth register of the

cylindrical section of the northern minaret,

a richly ornamented frieze naming al-Ḥākim

(Creswell, Muslim

Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, fig. 36; pl. 25, c, same as Flury, op. cit., pl.

29, 1;

Creswell, pl. 25, d, a better print of

Creswell Archive

negative

EA.CA.132; part of this section is shown in Flury, op. cit.,

pl. 29, 3).

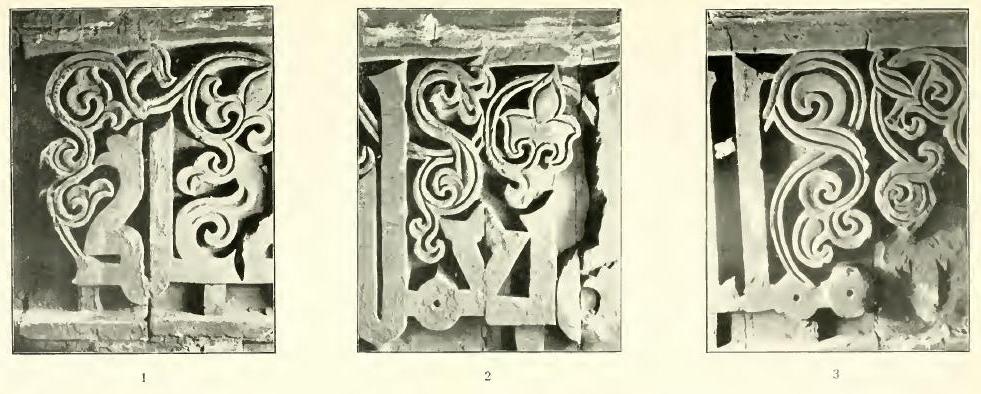

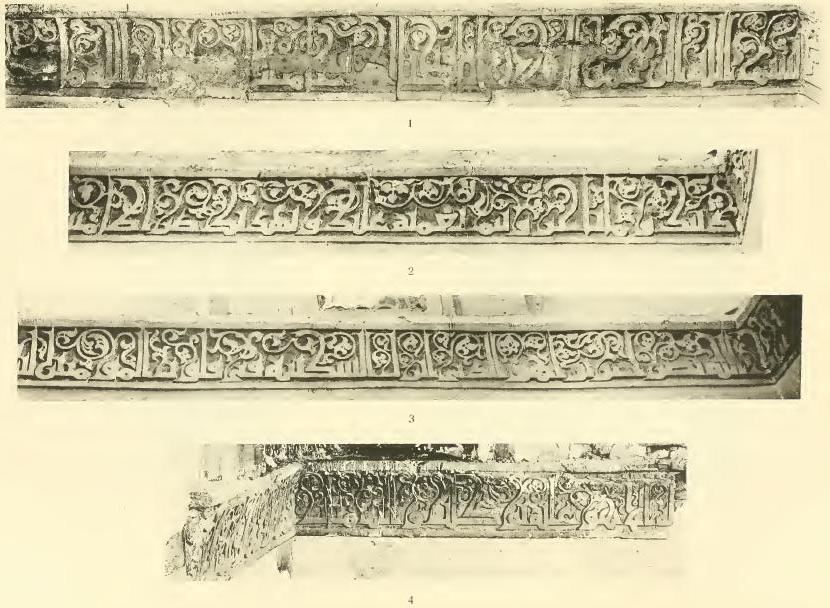

Figure 93. Northern minaret,

cylindrical section, inscription in fourth register; Flury, Ornamente, pl. 29,

1.

|

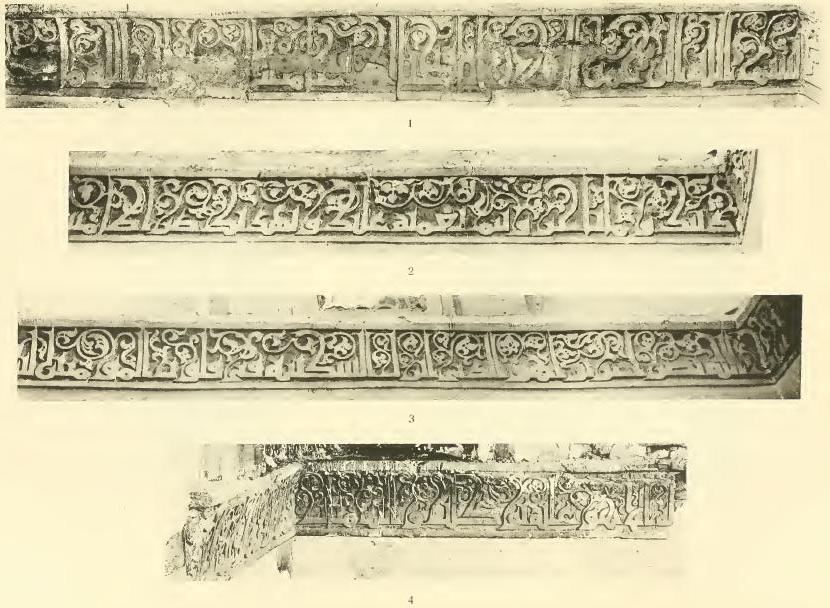

Figure 94.

Inscription in fourth register; Flury, Ornamente, pl. 28.

|

In the eighth register of the western minaret,

a lightly ornamented frieze 55 cm. high, naming al-Ḥākim; see

Creswell, Muslim

Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, fig. 40;

Creswell

Archive, negative EA.CA.120

(Creswell, Muslim

Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, pl. 29, a);

Flury, op. cit., pl. 32, 4 is an oblique view but not a good

one.148

In

the eleventh register of the western minaret,

a richly ornamented frieze 79 cm. high, naming al-Ḥākim

(see footnote above).

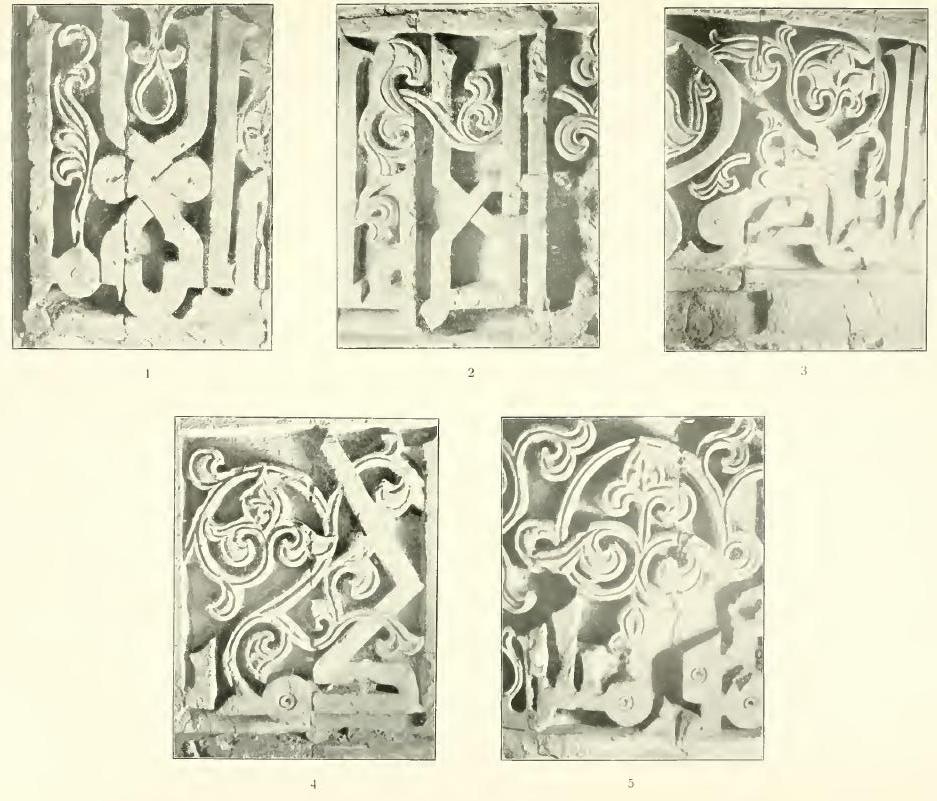

Figure 95. Western minaret,

inscription frieze of eleventh register; Flury, Ornamente, pl. 33,

1–3.

|

Flury's photographs are shown above; Creswell used others.

See

Creswell, Muslim

Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, fig. 40,

Creswell

Archive, negative EA.CA.3138

(Creswell, Muslim

Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, pl. 30, a),

EA.CA.3139, and

EA.CA.137

(Creswell, Muslim

Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, pl. 30, b, but cropped).

The following seem to be other views of the same frieze:

EA.CA.1637 (with the most ornament),

EA.CA.3140,

EA.CA.3141 (two views of the same section,

differently lit; the direction of slope of the handrail shows that

this is not the northern minaret),

and

EA.CA.3142 (with metal staircase).

A group of six limestone blocks in the Museum of Islamic Art,

Cairo, is said to have come from the Mosque of al-Ḥākim. Their ornament

appears to support that provenance and the text names

al-Ḥākim. They were first

published in 1903 and

their original location appears to be

unknown.149

Finally, the inscription on the exterior of the cubical

buttress constructed around the western minaret in 401/1010

may be considered.150

I am not an epigrapher and I am certain I am unaware of

some of the epigraphic literature on these inscriptions.

I am not concerned here with the style of the script,

but with its ornament, and specifically with whether that ornament

is related to the other carved stone ornament.

The lightly ornamented

inscriptions

in the medallion of the second register of the

cylindrical section of the northern minaret,

in the frame of the window

facing west in the third register of the same section,

and in the

frieze in the eighth register of the western minaret

offer little to analyze; the foliate ornament of the letters

in the frieze is hollowed out or slant-cut to develop internal

detail, unlike the letters,

while the foliate ornament of the other inscriptions

is as flat as their letters. There is nothing much to link

this ornament with the rest of the carved stone ornament.

The inscription on the exterior of the cubical

buttress constructed around the western minaret

resembles not the original stone ornament, but the stucco

of the antemihrab dome: both have foliate forms not seen

in the original stone ornament and particularly

in the stucco these forms are distinctively

articulated or enlivened with groups of small round

holes.151

Figure 96. Stucco inscriptions below antemihrab

dome; Flury,

Ornamente,

pl. 2

(cf.

Creswell, Muslim Architecture of Egypt, pl. 109, a, b).

|

The remaining inscriptions and those of the interior (of which more

later), as well as stucco inscriptions in the Mosque of al-Azhar,

have a prominent place in the discussion of so-called foliated

Kūfic (coufique fleuri,

Blumenkūfī),

which Flury and Adolf Grohmann consider first to have been developed

fully in Cairo and in these very

monuments.152

Whatever the priority of Cairo in the development of a style

of epigraphy that became widespread in the Islamic world,

Kūfic with stems and foliation attached clearly did not

come from Spain.

As few photographs, so far as I know, have been published of

the tall inscription friezes of the two minarets

my conclusions from the material at hand

must remain tentative. I think it clear that, like the

entrance to the staircase of the northern minaret and

the six loose limestone blocks,

its foliate ornament is entirely consonant

with that of the nonepigraphic ornament.

While Flury's photograph of the inscription

above the entrance to the staircase of

the northern minaret shows perhaps more than half of it,

the section published shows only a single leaf form, on a grooved

stem, but that leaf is familiar from the material already

discussed.

All of the leaf forms in the group of six limestone blocks in

the Museum of Islamic Art are found in the nonepigraphic ornament,

and one, at the left of the top row in Grohmann's illustrations

(no. 2638?) has a grooved ringed stem that splits at a small pointed

oval, then splits again on both sides, very much like the element

in the bottom right loop of the northwestern niche head on the

main entrance (see Figure 63).

The ornament of the inscription frieze of the fourth register

of the cylindrical section of the northern minaret is more

elaborate than that of, say, the window frames in seventh register

of that minaret: the grooved stems occasionally vary in width,

and a few leaves have more internal detail, but they otherwise

they are rendered in the same way, with grooved outlining and

occasional hollowing out. The especially noticeable five-lobed

leaf in the upper right of Flury's pl. 28, 3

(Figure 94) is paralleled in the

more crudely carved elements flanking the center of the top of

the window facing east (see Figure 32).

The split palmettes in which the two tops form stems curving

across each other

(Figure 93) are absolutely typical

of the carved stone ornament of the mosque; one of the two sets of

vertical axes of the main entrance frieze (Figure 1) is marked by such elements.

The inscription frieze in the eleventh register of the western

minaret seems to me quite similar, sharing variation in the width of

the grooved stems and the same five-lobed leaf, although in the

details published there is not so much internal detail.

I do not see how to separate the ornament of these original,

richly decorated inscriptions

from the bulk of the foliate carved stone ornament. It is

from the same craft tradition and distinct from that of the

stucco and the slightly later inscription on the exterior of the

buttress of the western minaret, so I conclude that it was all

executed by members of the same group of stonecutters, of whom

I imagine the calligrapher was not one.

Now while I would expect the foliate ornament of these inscriptions to

have been designed by the calligrapher, it may not have been so:

the calligrapher may have provided only the letters, or

he may have indicated the layout of the ornament but

not its details, or the man carving the inscription may have

substituted his own familiar motifs for those indicated

by the calligrapher. Perhaps most plausibly, the stonework

designer collaborated with the calligrapher (which is likely

in any case for the laying out of the inscription if not its

enlargement from a smaller-scale original). Such an arrangement

would not have required the stonecarvers to execute unfamiliar

foliate

forms, which they might not have been expected to do well.

It might prove interesting to find other cases in which

the ornament of architectural inscriptions can be compared with

contemporary but nonepigraphic ornament from the same monument.

147. Width

inferred from Creswell, Muslim

Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, fig. 33.

148. The reference in Flury's text, p. 48,

where the measurement is given,

is to the wrong plate. Adolf Grohmann,

“The Origin and Early Development of

Floriated Kūfic”,

Ars Orientalis, v. 2, 1957,

pp. 183–213, fig. 25 on pl. 10, is a shorter length of the

same section, from a different photograph, localized in the

“seventh band” in the caption because Creswell

bobbled his description of the inscription (never actually

using the word “eighth”, Muslim

Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, p. 96).

149. For the first

publications see

Bloom, op. cit., p. 35, no. 11. I have used the photographs

in Adolf Grohmann,

Arabische Paläographie

(Österreichische Akademie

der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-historische Klasse,

Denkschriften, v. 94), 2 v.,

Vienna, 1971, v. 2, pl. 24, 1; they also appear in Grohmann,

“The Origin and Early Development of

Floriated Kūfic”,

pp. 183–213, fig. 20 on pl. 7.

For their localization see Bloom, op. cit., p. 19, speculating that they

may have come from the main entrance, which is likely considering

the date of restoration work there.

150. Creswell, op. cit., v. 1,

p. 90, citing al-Maqrīzī; pl. 27, d.

151. There were also some

remains of a stucco inscription below the springing of squinch of

the dome in the south corner of the original prayer hall,

ibid., pl. 109, c.

152. For the contents of the

inscriptions see the appendix to Bloom,

“The Mosque of al-Ḥākim in Cairo”.

For “foliated Kūfic” see

Flury, Ornamente and for

al-Azhar

“Le décor épigraphique des

monuments fatimides du Caire”; Grohmann,

“The Origin and Early Development of

Floriated Kūfic”, pp. 207–13, and

Arabische Paläographie,

v. 2, pp. 139–40. The term “foliated Kūfic”

is poorly chosen: while flowers appear later,

in these inscriptions, anyway,

what grows from letters and stems

is leaves, rarely or never flowers.