|

Agroforest Systems 1.Food 2.Bamboo Bamboo Research 3.Riparian Riparian Species Author's Page |

Riparian Agroforestry

As the public begins to voice its alarm over the diminishing health of our water resources, policy makers are responding by drafting legislation that seeks to protect valuable riparian areas. Presently the regulatory forces that govern our waterways are asking for a proscription to all timber harvesting and agricultural practices within prescribed buffer zones along all endangered waterways. Consequently stream and riverside landowners are becoming angered at what is being perceived as another interference of government in private land ownership and property rights. Indeed establishment of a middle ground seems necessary between environmental protection and economic productivity. The question that must be asked is "is a permanent moratorium on commercial land-use within riparian areas the only possible way to protect these ecologically important habitat areas?" With federal funding, groups like the CRC & the Chehalis Basin Fisheries Task Force (CBFTF) have begun to address riparian restoration. An alternative to proscription of all commercial activity within riparian areas is the development of constructed agroforestry systems that meet the needs of wildlife and restore critical ecosystem functions while at the same time providing sustainable harvests of silvo-agricultural products. The sustainability of diverse riparian agroforestry systems relies on the value of secondary forest products as much as, if not more than, simply timber yields. By managing streamside forests for their inherent and enhanced diversity we relieve the burden imposed on the ecosystem by conventional methods of timber harvesting such as clear-cutting. Table 2 lists the many products and yields that can be designed into riparian reforestation plans resulting in a balanced and sustained return over time for landowners or land managers. Table 2: Products and Yields of Riparian Agroforestry System

Table 3 in turn lists the many functions that a riparian agroforestry system can provide in order to satisfy the needs of both the ecosystem and the farmscape into which they are designed. Along either side of Garrard Creek, as it runs through the Wild Thyme Farm's lower fields, we are beginning to develop such a reforestation plan that takes into account ecosystem restoration as well as sustainable economic development. By creating a model for diversified land management we hope to provide an example of resource stewardship that, if broadly applied, can help provide regional employment and economic opportunity within the means of our natural heritage. Table 3: Ecological Functions of Riparian Agroforestry System

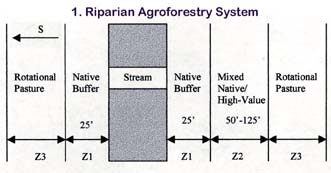

Our approach to designing riparian agroforestry systems employs a vegetated buffer that graduates from a restored native forest ecosystem into an increasingly mixed-use system of high-value timber and plant species and finally to a silvo-pastoral ecosystem capable of supporting low-density herds of cattle. Illustration 1 models the Riparian Agroforestry System we are developing at the Wild Thyme Farm. This design, though generally applicable in our region, is necessarily site-specific, as it must adapt to local environmental and agricultural factors. The three zones of use exemplified provide for important and unique functions to the total constructed ecosystem. Zone 2 (Z2) introduces a mix of native and non-native high-value timber species such as Paulownia, black walnut, ash, and willow varieties as well as such shade-tolerant understory elements such as mushrooms, berry crops, and floral greens. A greater degree of management is planned into this zone in order to take advantage of shorter-rotation harvests of small-diameter specialty woods, medicinal products, and propagation material. Zone 3 (Z3) introduces the potential for livestock in a silvo-pastoral setting where high-value and/or stock forage trees are planted on a wider spacing giving pasture grasses sufficient exposure to sunlight. Cattle range on short rotations allowing trees to be coppiced for fodder or bio-mass production. Periodic removal of grazing animals also allows for harvesting of pulpwood, nuts, or other by-products of tree crops. Agroforestry systems can be designed to varying levels of complexity appropriate to the landowner with the understanding that the more diverse the design becomes, the greater level of management, intensity, and sophistication it will require. The first impetus for design should be in the resolution of any environmental problems, and it is interesting to note that problems affecting farms, such as excessive nitrate runoff or erosion, can not only be ameliorated by tree crops but further turned to the advantage of the landowner. By way of example, many trees can tolerate surplus nitrogen, uptaking the otherwise pollutant and converting it into bio-mass. Other species, such as alder or black locust, prefer severely disturbed or eroded landscapes and therefore can be used to stabilize and build soils. Riparian agroforestry systems provide one of the greatest opportunities for sustainable economic development in the Pacific Northwest. This is largely due to the fact that the infrastructure supporting such development already exists in our region. Currently there are thousands of displaced or unemployed timber industry workers who are already familiar with forest management and can be retrained to replant and manage riparian areas as highly productive forest ecosystems. Many farmers also have small portable sawmills and other processing equipment. The market for sustainably managed and harvested special forest products in Washington State is already a multi-million dollar industry and the public's interest in these products is continuing to grow. |

|

|

|

|

|

www.wildthymefarm.com © 1998-2009 • 72 Mattson Road, Oakville WA 98568 USA. Tel: (360) 273-8892 |

Through the lower fields of our farm runs Garrard Creek, a tributary to the Chehalis, one of the largest rivers in Washington State. Its waters support seasonal runs of salmon, trout, steelhead and other populations of aquatic organisms. For centuries the Chehalis system has provided a food source for indigenous people and its annual flooding has replenished the fertility of bottomlands now devoted to agriculture. History has seen many uses put to this waterway and the indelible impression of our forefathers' industry are still present, etched into its character.

Through the lower fields of our farm runs Garrard Creek, a tributary to the Chehalis, one of the largest rivers in Washington State. Its waters support seasonal runs of salmon, trout, steelhead and other populations of aquatic organisms. For centuries the Chehalis system has provided a food source for indigenous people and its annual flooding has replenished the fertility of bottomlands now devoted to agriculture. History has seen many uses put to this waterway and the indelible impression of our forefathers' industry are still present, etched into its character. Logging and log transport, agriculture and settlement, and urban development have all left their marks. Riparian bottomlands offer the most productive and problematic soils in a farm's landscape. Because of these facts they have seen intensive use in terms of agricultural production as well as the greatest misuse in terms of environmental protection. The natural forest systems that once covered stream and river corridors have been systematically removed over time in order to increase cultivated land and pasturage.

Logging and log transport, agriculture and settlement, and urban development have all left their marks. Riparian bottomlands offer the most productive and problematic soils in a farm's landscape. Because of these facts they have seen intensive use in terms of agricultural production as well as the greatest misuse in terms of environmental protection. The natural forest systems that once covered stream and river corridors have been systematically removed over time in order to increase cultivated land and pasturage. We are developing this system based upon several factors important to our local landscape:

We are developing this system based upon several factors important to our local landscape:  Zone 1 (Z1) provides for stream health and wildlife habitat by providing shade, woody debris, erosion control, and the most limited of harvesting options within the whole system. This area is designed to ultimately return to a native climax forest through natural succession. As a strictly native plant zone it will also act, to a certain degree, as a genetic buffer between the non-native plant species in outer zones and the stream itself.

Zone 1 (Z1) provides for stream health and wildlife habitat by providing shade, woody debris, erosion control, and the most limited of harvesting options within the whole system. This area is designed to ultimately return to a native climax forest through natural succession. As a strictly native plant zone it will also act, to a certain degree, as a genetic buffer between the non-native plant species in outer zones and the stream itself.