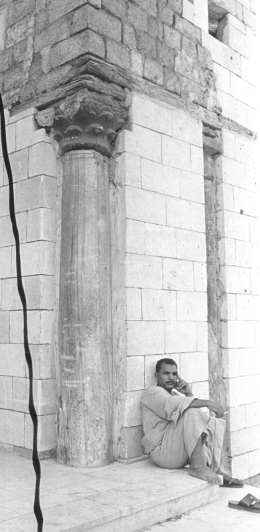

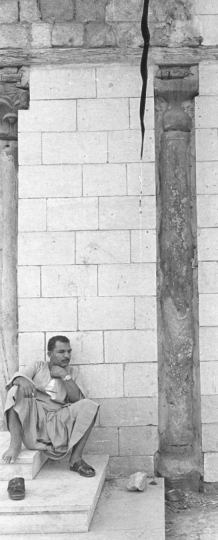

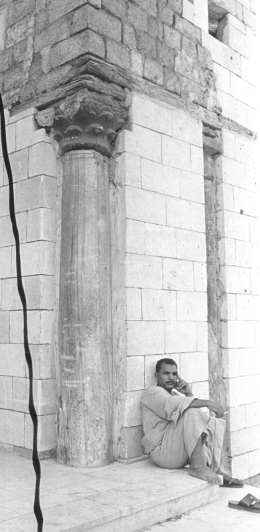

Figure 97. Main entrance, northwest side, columns from left to right.

Table of Contents

In the previous chapters I described and analyzed the ornamental carved stonework of the Mosque of al-Ḥākim by type and identified some of its sources (see particularly Chapter Three, Direct Integration of Foliate and Geometric Elements of Ornament). In this chapter I consider the carved stonework as a whole.

A somewhat fuller appreciation of the carved stone ornament may be obtained by considering the ensembles in which it is grouped.

When built the entrance block appeared taller than today because the ground level was lower. According to Creswell the projecting molding just visible in Figure 4 at the level of the exterior pavement of 1983 is half-round; he called it a “socle”. It has been rebuilt to run all the way around the block except for the opening to the passage. But Creswell, who was able to observe it only on the northeast side of the entrance block, did not show it in his bird's-eye reconstruction (fig. 44), in which nine steps are restored. He estimated the difference between the ground level when he wrote (apparently about the same as in 1983) and that of the time of construction as two meters.153 It is possible that some feature or articulation of the masonry below the half-round molding gave this basement zone the appearance of somehow supporting the niched zone above it.

The rest of the entrance block also had a more elaborate articulation than can be reconstructed on the basis of the remains on the northeast side, in at least two respects.

The decorated niches on the northeast side occupy only the lower portion of the presently visible entrance block (above the basement, that is). In the rebuilt version an inscription band, with additional decorative bands above and below, runs around the entire block except for the back of the passage, above the tops of the niche heads and below the springing of the tall pointed barrel vault of the passage.154 This is a perfectly defensible, if wholly conjectural, reconstruction of this portion of the original design (although its details are not): the portal of the mosque at Mahdīyah has a cornice at this level.155 But it leaves an upper zone undecorated; the Mahdīyah portal has another tier of niches in this zone (oddly, they are deep enough to hold objects, whereas those in the first tier are shallow). Surely there was some additional ornament in the upper zone, if only in paint.

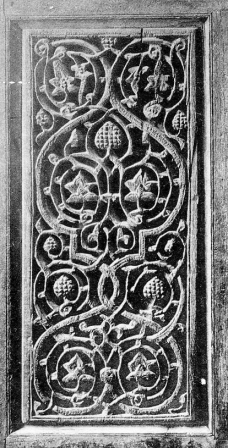

Figure 97. Main entrance, northwest side, columns from left to right. |

Then, too, the articulation of the northwest side of the block included columns, illustrated above. Two were Antique, while others were thin, with capitals in the shape Creswell called “clock-formed” and similarly shaped bases. This form had been naturalized in Egypt in the Mosque of Ibn Ṭūlūn and occurs in the antemihrab bay of the Mosque of al-Ḥākim. The columns, bases, and capitals were almost surely original features, although they have been eliminated in the rebuilding (see Figure 3).156 The two columns with apparently Antique capitals at the outer corners of the passage were noted by Creswell. As he remarked, the column on the left corner of the passage is shorter than the other; presumably it was damaged in the earthquake of 703/1303 and set again in its original place during the repairs made by the amir Baybars al-Jāshankīr (Baybars II) in 703/1304, which are commemorated by an inscription over the vault of the passage.157 This salvaging of an element no longer suitable for its original role in the decorative scheme of which it was a part may indicate that much of that scheme was also destroyed in the earthquake.

The buildings adjoining and obscuring the southwest (right) side of the entrance block were demolished in 1947, presumably exposing the thin columns on this side, with their bases and capitals.158 As Creswell did not note the thin columns, saying only that the southwest side of the entrance block “was found to be in a deplorable state”, perhaps they were not uncovered sufficiently to be recognizable until after The Muslim Architecture of Egypt went to press or it was not clear that they belonged to the original structure. When I photographed the entrance in 1983 the Mamlūk mausoleum that formerly stood on the northeast (left) side of the passage had been removed as well. As can be seen from Figure 3, there was nothing original on the left side except the frieze and the lower and upper cornices, which stepped back twice and continued toward the center (the upper cornice's palmette band could be seen in the top of the recessed area). On the right side there were the two thin columns shown above.

Creswell noted that there was space on either side of the passage for a pair of niches like those on the northeast side of the block (which is how the rebuilding has been carried out) but preferred the idea of only one niche on each side because it would have produced a more traditional triple-arch effect; his birds-eye reconstruction (fig. 44) shows one niche on each side of the passage, of the same height and form as those on the northeast side.159 The spacing of the thin columns is just right for a central arch or niche wider and taller than those on the northeast side, which would have produced a better effect. But the details of this treatment are lost.

I also note that main entrance block was very likely colored—if the ornament of the minarets was colored there is no reason all of the ornament should not have been—and that we cannot be sure that color was confined to carved ornament. Any flat surface, such as the upper zone, could have been embellished with painted designs, even if it was expected that they might have to be renewed.

With those considerations in mind I shall proceed to discuss the ornament that survives on the northeast side of the entrance block. The “socle” has already been mentioned.

The rotated squares may be seen as filling what the designer felt were voids; rotated squares are used in this profoundly unclassical way in blank arcades in later southern Italian church architecture. An analogous arrangement (squares within vertical rectangles) appears in flat stone on the facade of the Badia of Fiesole, outside Florence, of 1025–1028.160 The rotated squares could have been part of the prototype for the entrance (perhaps in paint or stucco). Alternately, or also, the designer may have felt that the richly carved cornices and the frieze between them would present too abrupt a change from the smooth masonry below without some element to interrupt that masonry. I imagine that they corresponded to some elements on the front (northwest side) of the entrance block, which could have been larger, round medallions.

I pointed out above (“Rotated Squares”) that the rotated squares and the niche heads correspond to each other in a chiasmic arrangement: the left rotated square and the right niche head are fairly curvilinear, while the right rotated square and the left niche head are fairly angular. I also pointed out that the borders of the rotated squares contrast with the fields of the squares in the same way. This correspondence indicates that the different parts of the ornamental scheme were thought about in relation to each other.

I discussed the lower cornice of the main entrance as an ensemble above (see “The Lower Cornice of the Main Entrance” and Figure 87). It is quite different from the upper cornice, which is composed of a a raking palmette band separated from a projecting band of lozenges and eight-pointed stars by a blank space (see “The Band of Repeated Palmettes of the Main Entrance”, “The Upper Register of the Upper Cornice of the Main Entrance”, and Figure 79). The other carved projecting borders that could be considered as cornices are all on the western minaret, except for what I have termed the border of the upper zone of the main entrance. Most of the western minaret cornices do not resemble the lower cornice. The exceptions are the dentil borders of the seventh and eighth registers of the western minaret, discussed below.

Overall the strongly projecting lower cornice has a prickly texture not paralleled elsewhere.

I have discussed the main entrance frieze extensively above; it remains to remark that the foliate border that wraps entirely around the frieze (reducing its friezelikeness by doing so) employs the most original of foliate border designs in the Mosque of al-Ḥākim (see “Borders of Undulating Stems with Alternate Trefoil Leaves”), that the carved area is quite deliberately set off by a surrounding blank area, and that the frieze does not project from the plane of the wall like the cornices above and below it, but, by contrast, is carved back into the depth of the masonry.

The upper cornice, if I have identified it correctly as such, combines the raked border of repeated palmettes with a border that steps out from the wall surface like the lower cornice; taken together, it is a transition to a new plane of masonry (Figure 79). The upper border, although inconsistently executed, is more elaborate in design than its context seems to require (would not one of the simpler lozenge bands have sufficed?), but perhaps its complexity was intended to contrast with the relatively simple border below.

The niche heads and the one preserved niche arch are freely composed rather than strictly repeating designs, all with a sense of verticality lacking in field designs such as the rotated squares. The foliate motifs and carving are very similar in all three elements, and although there is a reduction in depth of carving from the niche heads to the outer border that helps distinguish the components of the ensemble there may well have been a contrast in the use of color from one element to the next, as well. The right side of the inner border of the southeastern niche head is particularly stylishly carved—what a pity that it is not original! The frames are peculiar to the niche heads, and are not part of any longer border.

The border of the upper zone of the main entrance resembles the dentil borders of the seventh and eighth registers of the western minaret in alternating projecting blocks with wider segments lying in the plane of the raked molding (see “The Dentil Borders of the Seventh and Eighth Registers of the Western Minaret”). The projecting elements of the upper zone border are palmettes rather than blocks; the segments between them are wider than in the minaret borders, and the details of the foliage differ. Despite that difference they would look much more similar were it not for the difference in carving: the wider segments of the main entrance border are carved in quite low relief although modeled in the way most of the foliage of the stone ornament is, but both the projecting blocks and wider segments of the minaret borders are carved in a sort of flattened bevelled style (cf. the bevelled style carving of the wood facings of the tie-beams of the antemihrab bay161).

The minarets employ ornamental ensembles different from those of the main entrance.

Considering the minarets themselves as ensembles, the ornament of the northern minaret is concentrated in the socle, the window frames, medallions, and two friezes, one mostly epigraphic, the other the palmette frieze. The socle is enlivened with a bordered zone. The raked inscription frieze is given borders above and below. In the cylindrical section, where the registers step back, they are capped by plain half-round moldings except above and below the inscription frieze.

By contrast, in the western minaret the lowest four registers are topped by plain moldings of complex profile and contain a frieze of carved ornament with foliate bands above and below (the frieze of the third register and the bands of the second and fourth registers). This zone is a sort of socle, too. Above, nearly every register is topped by a carved band, most of them geometric (see Chapter Seven, Foliate Bands and Borders and Chapter Eight, Geometric Bands and Borders). There are two inscriptions, in the eighth and the eleventh registers; a frieze in the tenth register that may have been intended to be seen together with the inscription in the register above; a mostly lost geometric parapet; a crestinglike frieze, and a register filled with rotated squares; the sole published ornamented window frame (from a set of four) is an application of the undulating foliated grooved stem atop a fleshy but ungrooved stem (also used for the frame of the entrance to the staircase). Except for the geometric border around its exterior opening, the niched room is not part of the same ensemble as the exterior. The effect of this ornament is more diffuse than in the northern minaret (seen better by comparing Creswell's elevations, fig. 36 and 40, than in the birds-eye reconstruction, fig. 44).

The only published ornamented window frame of the western minaret is filled solely with an undulating foliated grooved stem atop a fleshy but ungrooved stem, which otherwise appears as a border design. All the other ornamented window frames are in the northern minaret, as are the ornamented window screens and balustrades. With one exception in the third register, where a geometric outer border is used, these windows frames all seem to be examples of two-halved frames.

The windows of the third register of the northern minaret combine pictorial screens, inscription borders, and either rather lively foliate or geometric outer borders; the only geometric one is a unique lozenge pattern. (See “The Frame of the Window Facing East of the Third Register of the Northern Minaret”, “Borders of Undulating Stems with Alternate Trefoil Leaves”, and “The Screen of the Window Facing North”). Care was taken with these window frames, and it may have been intended that the ornament is broadest in the screens and finest-grained in the outer borders.

The only published window frame of the fifth register appears in Creswell's elevation of the northern minaret (fig. 36), and I can say little about it except that it is composed of only one pattern.

In the window frames of the seventh register the most remarkable foliate-geometric designs (in the vertical sides) were juxtaposed to openwork balustrades; of the two out of three balustrades surviving one is of conventional design and the other (in the window facing north) is a unique composition, forming a five-pointed star within a frame of curving stems. Perhaps here the intended effect was a contrast of openwork with the (painted) frame, of a somewhat denser texture, separated from each other by a generous plain zone.

The rotated squares of the western minaret (on which more below) are all filled with geometric designs and all but one has a foliate border, presumably by way of contrast. The geometric medallions of the eighth register of the cylindrical section of the northern minaret, unusually, have no consistent borders; the other medallions are combinations of inscriptions and geometry. The spandrels and ceiling of the niched room are free exercises in design with a limited repertoire of elements.

I have argued both that the direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament that distinguishes the carved stonework of the Mosque of al-Ḥākim came from Umayyad Spain and that stonecutters themselves may have, too, probably after 366/976 or 370/981 (see “Madīnah al-Zahrā' and the Mosque of al-Ḥākim”). The Mosque of al-Ḥākim was begun in 380/990 and completed after 393/1003. We cannot know whether the ornament as executed was planned when the mosque was begun or only later, but it is common in construction projects for the design to change over time, and thus the designer or designers of the ornament may have been in Cairo for as long as a quarter century before creating the ornament that was actually carved. If so, they would have had plenty of time to pick up new forms. While Madīnah al-Zahrā' is still incompletely excavated and published, so that it is difficult to say that a given element does not exist there, it is likely that the suggestions of the bevelled style that appear in the Mosque of al-Ḥākim stonework (see above) were adopted by its designers in the course of residence in Cairo. I see no need to look elsewhere for the sources of the carved stone ornament.162

In this study I have avoided the word “architect” in favor of “designer” in referring to the man who designed the carved stone ornament. Architect and designer (or architects and designers) may well have been one and the same, but need not have been, and I do not see evidence to decide one way or the other. An architect might well have indicated where he wanted carved ornament and left the details of it to a designer; if architect and designer were not the same, then the designer could have been the head of the stonecarving workshop, but again need not have been. These are roles in the design process.

At the largest scale it was, of course, an architect who determined the form of the mosque. The two minarets are not only ornamented differently, they have different basic shapes. Creswell considered both together:163

Comparison of Decoration of the Western Minaret with that of the Monumental Entrance. Each minaret is of beautifully dressed stone, pierced at intervals with windows which originally gave light to the spiral staircase within. But no one can fail to be struck with the fundamental difference between the two, both in form and decoration. Although the northern minaret has two fine bands, one calligaphic, the other of arabesque, its decoration is chiefly concentrated on the many beautiful window-frames with crisply carved calligraphic borders and on their beautiful pierced balustrades, several of which are still preserved, whereas in the western minaret the windows are small, narrow, and generally perfectly bare, and the decoration is concentrated on four splendid bands of ornament, two calligraphic and two of arabesque. In addition to this, the plain torus moldings of the northern minaret are replaced by highly decorated ones.

One cannot help concluding that we have to do with the work of two different architects. But although the decorative scheme of the western minaret is so different from that of the other, it bears a close relationship to that of the monumental entrance. The lower part of the panels of the latter are decorated with squares of ornament placed lozenge-wise, which is the same as the scheme adopted in the lower part of the minaret. The central part of the band of arabesque is related to the ninth band of the minaret (Plate 30 a and c) and its outer border is exactly like that of a window in the second octagonal story (Plate 32 a). The mouldings above and below it belong to the same family as those of the minaret. The band which runs across below the hoods somewhat resembles the band which runs along the cornice of the second octagonal story. There can, therefore, be little doubt that the western minaret and the monumental entrance are the work of one architect, the northern minaret of another.

This is good analysis, but the conclusion is perhaps simplistic. I do not think the minarets differ in form because two different architects willfully went their own ways, but because someone, probably the client, required them to be different. There may have been one, two, or more architects, and they may have worked in consultation, a man working on one minaret contributing to the other. Their contributions need not have been equal.

The ornament of the two minarets may also have differed because it was required to. There is some evidence of deliberate contrast in the fact that the cylindrical northern minaret is decorated with round medallions and not rotated squares, whereas the square and octagonal western minaret is decorated with rotated squares and not round medallions. Given the emphasis on polygonal forms in the decoration and the chiasmic contrasts I have pointed out in the decoration of the main entrance, I am inclined to think that this difference is significant.

The originality of the carved stone ornament is both considerable and, at least in places, deliberately displayed.

It is not clear that the use of a frieze across niches and below their arched niche heads in the main entrance is an original idea in the Mosque of al-Ḥākim, but it is the first time it appears in extant monuments, and probably should be connected with the use of rotated squares and medallions to decorate what would otherwise be blank spaces.

The main entrance frieze and the palmette frieze of the northern minaret are both original in their interlacings, the main entrance frieze certainly in its development of direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament far beyond what was attempted at Madīnah al-Zahrā'. The originality of the design is emphasized by the use of three bands against the two alternating axial foliate forms. It is true that no one has mentioned the three bands before in print, I imagine because no one has noticed that there are three; it takes work with colored pencils to discover them. Unless the structure of the frieze had been made more apparent originally by a similar application of color I doubt that many viewers would have perceived the nature of its interlace, merely that it was an interlace. The point of complicating a two-strand intertwining lozenge pattern to add a third strand to display originality implies that the bands were in fact painted different colors.

The frieze of the third register of the western minaret has no prototype I know of. The working of the foliate forms around the geometric ones is a new venture in foliate-geometric interlace.

The window frames of the seventh register of the cylindrical section of the northern minaret develop a scheme from Madīnah al-Zahrā' but combine it with variation in the elements used in the ascending portions, which is new (see “Variation in Ascending Foliate Patterns”, above).

Most of the foliate borders do not seem unusual, although closer study might find some that are; but the undulating foliated grooved stem atop a fleshy but ungrooved stem was never used before or since, and it is hardly a natural invention. It must have been invented for some reason, and a deliberate display of originality seems most likely to me.

The geometric borders are based on long-established combinations of elements and ways of combining them, so there may be no geometric border that is novel. But the wide variety of them, where a far smaller selection would have given the same impression, is again a deliberate display of the designer's virtuosity.

The friezes, the window frames, the borders, the medallions, and the rotated squares are all deliberately varied, as though it was desired to give the impression that no two were the same. This variety need not have been a client requirement, but the ability to create it could have recommended the designer to the client, who may have wanted something new or “the best”.

The clearest use of geometry as a display of originality is in two of the rotated squares of the western minaret, which, unlike the rotated squares of the main entrance, are mostly concerned with torturing a geometric figure of some number of axes into one of another number of axes, regardless of aesthetic consequences.

In one of the window frames of the seventh register of the cylindrical section of the northern minaret (“The Window Facing West”) the insertion of five-pointed stars in addition to six-pointed stars in the sixth cycle ruins the interlacing of the two stem sets, due to their odd number of points. I have suggested that the use of the five-pointed form was a client requirement, and I think the same applies to the geometries of the rotated squares, the window screens, and the medallions of the eighth register of the cylindrical section of the northern minaret. The designer was told to use geometric figures of certain numbers of axes, and tried to do so inventively, perhaps even introducing the variation in ascending foliate patterns of the window frames in the process.

Throughout previous chapters I have pointed out errors in the execution of the carved stone ornament of the Mosque of al-Ḥākim. There are two sorts of errors: errors in executing interlacing and errors in laying out repeating patterns, mostly in the geometric borders. Such errors are not unknown in Late Antique and Islamic architectural decoration—I pointed out some possible errors in Hagia Sophia and at Samarra above—but in the Mosque of al-Ḥākim, which was a monument of the highest importance, they seem exceptionally common and egregious, occurring even in the most prominent places (in the main entrance frieze and the socle of the northern minaret). That such errors were tolerated by al-Ḥākim (or his advisors), may reflect on him, but in what way I leave aside. Such errors were not usually committed in the first place, and that they were here indicates that something went wrong.

Both kinds of error can be explained in relation to the method of production of the carved stone ornament.

It is most likely that for everyone's convenience all the stone was carved on the ground and then set in place, probably with only some touch-up work (and painting) done in situ.

It is observable that in general the larger-scale ornament was laid out, presumably by drawing or painting, on stones of equal width, such that vertical axes of the design fall on vertical joints. Even when the stones of a given piece of ornament differ in width the vertical axes of the design still tend to fall on vertical joints.164

The smaller-scale ornament does not seem to have been dealt with in the same way. Of the foliate borders too little has been published for me to feel confident in generalizing; for the geometric borders it is clear that in at least some cases stones of irregular width were used, as in the bands of the fourteenth and fifteenth registers of the western minaret (Creswell, Muslim Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, pl. 32, b).

The designer of the ornament, or someone acting fairly directly under him, must have laid out the larger-scale, more complex designs on stone; there are no errors in layout in these designs (including the rotated squares and the medallions), nor in the inscriptions (inscriptions are not repeating designs and could not be trusted to someone junior to lay out). The inscriptions aside, use of stones of equal width would have made it possible to use a template the size of a single stone.

But for the smaller-scale, simpler geometric borders the designer could have supplied a sample, one design repeat long, and left it to someone farther down the hierarchy to lay out the design by repeating the sample across stones of any width. This procedure failed, resulting in errors in layout, perhaps because whoever did the actual laying out had to make decisions about how to apply the design to stones of varying width, and inappropriately adjusted the design so that axes of the design would coincide with joints between stones (cf. the more intelligent adjustment made in the frieze of the third register of the western minaret, Creswell Archive, negative EA.CA.129 or Muslim Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, pl. 28, c). The border of the socle of the northern minaret presented the additional problem of how to manage the vertical sections of the design, and clearly whoever solved the problem did so poorly. For the simplest designs it is also possible that they were executed directly by stonecarvers (themselves misapplying the rule about vertical axes and joints) without adequate supervision.

In any event, quality assurance was inadequate, pointing to a failure in management of the work.

Errors in executing interlacing patterns most likely resulted from a stonecarver misinterpreting the correctly laid out pattern on the stone he was working on. Along with variation in detail (as in the palmette frieze), these misinterpretations suggest that the stones were carved separately, at times by different men, as opposed to the method of work of a mosaicist or woodcarver, who worked down an entire border, applying a consistent rule for its intertwining or interlacing. The mosaicist or woodcarver understood what he was doing but the stonecarver was blind to the bigger picture because he was working on only part of it. In the palmette frieze the inconsistency of interlace occurs within rather than at the edges of the stones, so this irregularity cannot have resulted from confusion about how the design should run at the stone joints. It must have stemmed from uncertainty about or indifference to how the design as presented to the carver was to be executed. For the main entrance frieze the pattern would have been drawn out freehand rather than by use of a template, as in places the pattern was squeezed to fit. Again, working on only short sections of the pattern, it would have been easier for the carvers to make errors in interpreting the over- and undercrossings of the drawn or painted pattern than if they had been constructing the pattern as they went along, on stones already in place.

In the case of errors in executing interlacing patterns the results might have been tolerated if it was thought they would be masked by paint. But still, these errors should not have happened, and something went wrong in the operation of the workshop. What was it?

There are so many possible answers to that question that instead of choosing one I suggest a range, divided into three categories: incompetence, absence, and client pressure.

Possibly the designer, or whoever was supposed to be supervising the work and checking that it was done correctly, was simply incompetent, perhaps promoted to a position of responsibility beyond his abilities.

Possibly this person (or persons) was absent from the workshop while the carving was being done. He could have been taken ill, he could have died, or he could have been engaged on another job. For example, he could have been working on the Fāṭimid Palace with a team composed of the best managers and carvers, but supplying the Mosque of al-Ḥākim team with designs on which he was unable to coördinate with them successfully.

Or perhaps the client required the work to be executed in such haste that it was just done sloppily, and accepted by the client regardless (the long period of construction tends to speak against this possibility, but does not eliminate it).

In any case the client may have been either ignorant of or indifferent to the mistakes being made.

The carved stone ornament may be exploited to shed light on later Islamic art. It includes original and unusual designs and design concepts, some drawn from Umayyad Spain at the end of its artistic development. Very few of these were repeated in later monuments. Of them by far the most important is direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament, which contrasts with other uses of foliage with geometry.

Direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament does occur in later Islamic art and architecture, but only rarely and never so systematically as in the Mosque of al-Ḥākim and its Spanish sources. Here are nontrivial examples I have found:

Figure 98. Aqmar Mosque, facade, detail. |

On the facade of the Aqmar Mosque in Cairo (519/1125) a mihrab is pictured in stone. It has what appears to be an openwork screen formed of interlacing grooved bands that make a six-pointed star in the center (cf. the balustrade of the window facing west in the seventh register of the northern minaret); the lowest of these bands grow from foliage in the bottom corners.

In a limestone mihrab from the Temple of Baal at Palmyra, now in the National Museum, Damascus, and attributed to the late eleventh century A.D., the border of the niche head appears (from the only photograph available to me) to be constructed from zigzagging stems that sprout foliage.165

In Cairo, the arch over second window from the left of the entrance in the facade of the Madrasah of Najm al-Dīn Ayyūb (640–41/1242–44) contains long cusped stems that are connected with other foliate elements and also follow the smoothly curving upper side of the arch (Creswell, Muslim Architecture of Egypt, v. 2, pl. 34, d).

In the painted ceiling decoration of a mosque in al-Waḥs, Yemen, dated 737/1337, circles and knots sprout foliage.166 There is a great deal of painted decoration in this mosque and I may have missed some other examples of direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament, but it is certainly not common.

Figure 99. Mosque of Sultan Ḥasan, detail of portal. |

An example in carved stone of a kind of design that also appears in other media comes from the Mosque of Sultan Ḥasan in Cairo (in use by 761/1360). Here the stems of the foliage form sharp angles around the center of the design.167

In the Maghribī stucco decoration of the īwān-hall of the Mausoleum of Muṣtafā Pasha, ca. 667–72/1269–73, knotlike interlaces are topped by palmettes (Creswell, Muslim Architecture of Egypt, v. 2, pp. 178–80, pl. 56, b). In the Alhambra similar designs occur, but the knots are woven from the uprights of letters.

There are also later examples of direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament in the east (I have not made a thorough search). For example, in a stucco mihrab on the roof of the Masjid-i Kūchah-i Mīr in Naṭanz, 712–28/1312–28, foliate elements spring from the doubled bands that intersect to form lozenges.168

What is much more common in later Islamic art than direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament is complete separation of foliage and geometric designs in separate fields, separate foliate and geometric designs interlacing with each other, or separate foliate and geometric designs not interacting with each other at all.

Figure 100. Wooden mihrab from the Mashhad of Sayyidah Ruqayah, details; Tarchi, L'Architettura e l'arte musulmana, pl. 39. |

Two examples from the wooden mihrab of the Mashhad of Sayyidah Ruqayah in Cairo (1154–60) show interlacing of foliage and a geometric framework of bands decorated by beads, which is usually called “strapwork”. Although I have used the term in the past, I wonder whether it is not anachronistic; I now prefer “beaded bands”. In the horizontal panel the beaded bands are not integrated with the foliage; in the upright panel they curl up into foliage at top and bottom, still integrated.169 This curling up of the geometric framework continues in woodwork as late as the wooden balustrade of the Dome of the Rock, ca. 595/1199–1200 according to its inscription, but possibly a composite work.170 Occasional examples in wood and bone occur in Cairo down to the end of the Mamlūk period.171

Conversely, in some examples of both woodwork and stucco some stems in a design are bound off at the top or bottom in an angular way, forming squares.172

But in general, in Islamic art after the fourth/eleventh century foliage remains separate from geometry.

In Cairo, by the end of the seventh/thirteenth century there are designs in which interlacing foliage lies beneath a geometric framework without interlacing with it.

[Link: Cairo, Mausoleum of Fāṭima Khātūn, detail of stucco (Muslim Architecture of Egypt, v. 2, pl. 59, a), Creswell Archive, negative EA.CA.4552.]

One such design occurs in stucco in the Mausoleum of Fāṭima Khātūn, 682/1283–84.

Figure 101. Mausoleum of the Madrasah of Qaytbay, dome. |

But the most familiar such designs adorn the stone domes of several late Mamlūk mausolea, such as the mausoleum of the Madrasah of al-Ashraf Qaʿit Bay, completed 879/1474.173

No greater contrast with direct integration of foliate and geometric elements of ornament could be imagined.

153. Muslim Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, pp. 69 and 292; for the profile, fig. 24, b.

154. Bloom, Arts of the City Victorious, pl. 46.

155. Creswell, op. cit., v. 1, pl. 1, b.

156. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture, 2nd ed., v. 2, p. 243, thought the first appearance of the capital form in Islamic architecture was at Samarra. For North African Fāṭimid capitals, which are much different, see Patrice Cressier, “Le chapiteau, acteur ou figurant du discours architectural califal? Omeyyades d'al-Andalus et Fatimides d'Ifrīqiya”, Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā', v. 7, 2010, pp. 67–82.

157. Creswell, Muslim Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, p. 66.

158. Ibid., p. 70, n. 4, for the 1947 demolition; pp. 71–72 for work within the passage.

159. Ibid., p. 72.

160. Domenico Cardini et al., Architectural Guides Florence, 2nd ed., Turin, 1998, p. 26.

161. Creswell, op. cit., v. 1, p. 84 and pl. 20, b, c; Barrucand, “Premier décor”, pl. 14.

162. However, the most impressive undecorated moldings, those of the socle of the northern minaret, might presuppose some acquaintance with classical architecture. Did they come from Spain or was there some other source?

163. Op. cit., v. 1, p. 101.

164. In the main entrance the frieze and its cornices had to be fitted to the widths dictated by the articulation of the block by niches, and in any event they may well have been reset in part after the earthquake of 703/1303. The border of the upper zone of the main entrance is carved on stones of unequal width. The six inscribed stones that presumably came from the main entrance are not of equal width; possibly equal-width stones were specified only for repeating patterns.

Of the friezes of the western minaret, and generalizing from the sections published, those of the tenth and sixteenth registers are carved on stones of equal width. That of the third register is not entirely carved on stones of equal width (see Creswell Archive, negative EA.CA.129 or Creswell, Muslim Architecture of Egypt, v. 1, pl. 28, c, which may show an adjustment required toward the corner, or the need to make use of stones that were not supplied in the dimensions specified). The parapet is too incompletely preserved to judge.

The rotated squares are carved on pairs of stones divided down the center on one diagonal, although in the rotated squares of the main entrance the design is not exactly divided along the joint between the two stones.

165. Anne-Marie Eddé et al., L'Orient de Saladin: l'art des Ayyoubides, Paris, 2001, p. 32.

166. Barbara Finster, “Survey Islamischer Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler im Yemen, Das Gebiet von Wuṣāb”, Archäologische Berichte aus dem Yemen, v. 11, 2007, pp. 433–76, pl. 14.1, 19.1 (for dating see p. 450).

167. See Michael Meinecke, Die Mamlukische Architektur in Ägpten und Syrien (648/1250 bis 923/1517) (Abhandlungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo, Islamische Reihe, v. 5), 2 v., Glückstadt, 1992, v.1, for this (pl. 81), a similar design elsewhere in the building, and comparative material.

168. Bernard O'Kane, “Naṭanz and Turbat-i Jām, New Light on Fourteenth Century Iranian Stucco”, Studia Iranica, v. 21, 1992, pp. 85–92, repr. O'Kane, Studies in Persian Art and Architecture, Cairo, 1995, fig. 6.

169. Illustrations from Ugo Tarchi, L'Architettura e l'arte musulmana in Egitto e nella Palestina, Turin, n.d. [1922], pl. 39; for the date, Mohamed Abbas in Bernard O'Kane, ed., The Treasures of Islamic Art in the Museums of Cairo, Cairo, 2006, p. 59.

170. Sylvia Auld, “The Wooden Balustrade in the Sakhra”, Ayyubid Jerusalem, ed. Robert Hillenbrand et al., ch. 5, pp. 94–117.

171. Wooden panel from the minbar of Sultan al-Manṣūr al-Dīn Lājīn, 1296, David Collection no. 7/1976; wood and ivory panel, Egypt, fifteenth century, David Collection, no. D 16/1986; Kjeld von Folsach, Art from the World of Islam in The David Collection, Copenhagen, 2001, fig. 431 (minbar) and 409 (ivory).

172. See woodwork from the Mosque of al-Ṣāliḥ al-Ṭalā'iʿ, Cairo, drawn by Barbara Finster, op. cit., pp. 223–78, fig. 86. In a stucco window of a mausoleum in Ẓafār, Yemen, of the early seventh/thirteenth century, the angularity occurs at the bottom; ibid. pl. 117, a.

173. Meinecke, op. cit., v. 2, p. 399; Christel Kessler, The Carved Masonry Domes of Mediaeval Cairo, London, 1976, pl. 34. Kessler, p. 30, distinguishes three layers in the composition, the third being the “plain centres of the medallions”.